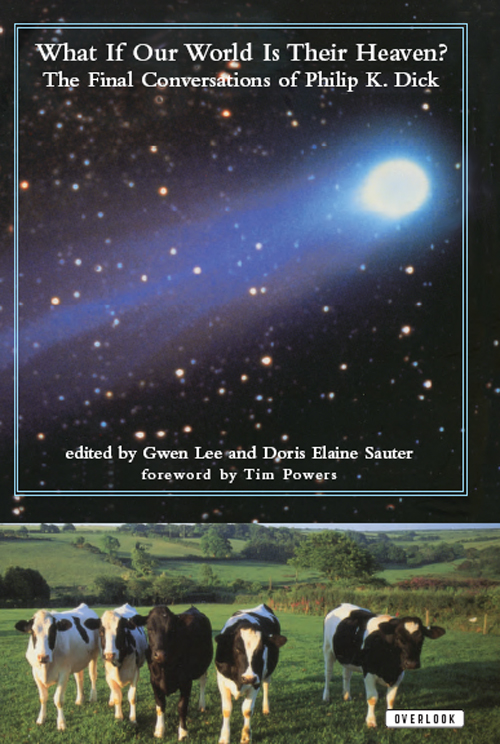

First published in the United States in 2000 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

Copyright 2000 by Gwen Lee and Doris Elaine Sauter

Introduction copyright 2000 by Tim Powers

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-228-8

This book is dedicated to our mothers, Mattie Hurst Gype and Mae Helen Sauter.

F ROM G WEN:

My first thanks is to PKD for his friendship, he was everything a friend could be. His intellectual generosity was boundless. He was as excited about the interview as I was. He made it an extraordinary experience.

Thanks to my husband, Wibert Lee, for his support of this project from its inception.

Thanks to David McDonnell at Starlog for his advice and support over the years.

Finally I would like to thank D. Elaine Sauter for her friendship, for bringing Phil into my life, for bringing life into this manuscript and getting it published. I am fortunate to have such a multi-talented friend!

F ROM D ORIS:

Thanks to my friend Gwen, who had the foresight to interview Phil, an interview which turned out to be the last record of one of the most gifted writers of this century. Thanks also for her support during and after Phils final illness; shared grief is so much easier to bear.

A heartfelt thank you to all the members of the Dallas Writers group, especially Jan Blankenship, Amy Bourret, Robert Burns, Victoria Calder, Will Clarke, Fanchon Knott, David Norman, Christine Phillips and Sandra Sadler, for their support and suggestions during the publications phase of this book.

Grateful thanks also to Lawrence Sutin for his kind words of encouragement after Phils death and during the preparation of this manuscript.

Gratitude also to James A. Padova, M.D., and everyone else at the Hematology-Oncology Group in Orange County who kept me going long enough to get here. And hopefully beyond.

And many blessings to Tim Powers, who told me in his Santa Ana living room years ago: you can.

TIM POWERS

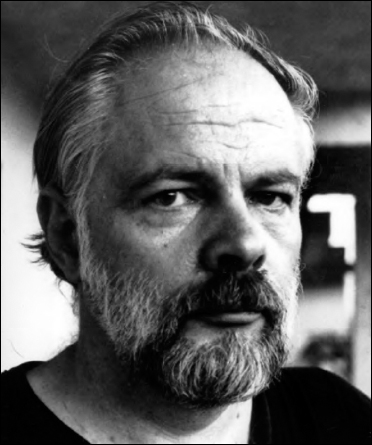

Less then two months after these interview sessions were taped, Philip K. Dick would be dead. He never lived to see the finished movie Blade Runner, and his proposed next novel, The Owl in Daylight, didnt go much further than the musings in these talks.

But what talks! These conversations vividly bring back the recollection of spending an evening with Philip K. Dick. Im glad the text hasnt been edited to take out all the off-track remarks and the repetitions of you knowthis is simply transcription, and it gives the reader the real sense of how the man spoke. His conversation was always fascinating, even when the beginning of a sentence, if not the whole topic, had been left behind in the mercurial free-association of his thoughts. I remember the pleased satisfaction Id feel when Id occasionally throw in what seemed to be a related speculation, and see his eyes widen and hear him say something like, Yes, of course, and More often, I suppose, he would nod politely, say, Yes, yes, but and then resume where he had left off.

Many of the conversations hed have with Doris Sauter and K. W. Jeter and me were gonzo-theology, and while the rest of us were hampered with fairly fixed convictions, Phil would shift creeds almost day to day, like a fencer shifting among guard-lines.

And though he would shift his creedsone day deciding that the real truth was to be found in Orthodox Judaism, the next day that the Gnostic Essenes had found all the secretshe was never cynical. Well, how could he be? Something very big had happened to him in February and March of 1974, as he describes in this book, and he was on the one hand too honest with himself to minimize it and on the other hand too curious and erudite not to pursue it with his whole mind. Always the minimal hypothesisthe possibility that he had simply suffered some kind of psychotic episodewas objectively considered and eventually found inadequate to explain all the facts.

For some, though, the minimal hypothesis is satisfactory. I have read that Dick didnt dare move from a shabby apartment, because he believed that was where God knew how to reach him; and that he was a misogynist recluse; and that he once killed a cat with the power of his mind. None of these, actually, is truebut the image of the crazed, mystical hermit-genius is an attractive and easily swallowed one, and people have a fondness for easy summaries, even if the summaries are wrong and the truth is something a good deal more complex.

I think its impossible to read these interviews, or Valis, or The Transmigration of Timothy Archer, and conclude that Dick was irrational. His sense of the absurd is everywhere as palpable as his bewilderment at his experiences, and he is at least as aware of the implausibility of some of his theories as his listeners or readers are. I remember frequently being convinced by some outre notion of his, only to be cut off in mid-credulity by his abrupt decision that the notion was based on faulty logic. His objectivity, his clear-eyed humorhis self-derision, evenwere too briskly realistic to permit the cocooned egotism of insanity.

If these interviews are in fact not the record of a madman, though, they are at least the testimonyhumorous and whimsical, but nevertheless clearof an artist who is killing himself for his art.

As Doris Sauter notes in her insightful introduction, Dick did write each of his later novels in eight to twelve days. I remember him calling me up to come over to his apartment and read some early pages of Valishe only emerged from his office long enough to give me some typed pages, and then he was back in there, typing away. I remember that he called to me to ask how to spell certain words, and its fun now to find them in the published text and see what part of the book he was writing as I sat in his living room and eventually I called some comments to him and then let myself out. I believe he wrote Valis in twelve days; he must have eaten and slept during that time, but Im certain it was not nearly enough.

Its enthralling to hear Dick explaining how he wrote his books. Some of it is funny, as when he explains how to drop evidence of a technical development like biochips into a science-fiction story:

Thats another technical device, you casually have one character say to the other, Where did you put the biochips? I put them back in the cupboard where they belong. Thats all you need to say See, its amazing how easy it is to write if you know how

But only a few pages later we see him seriously address the constructing of a story. Lets do it right now, he says, lets work the book out. And for the next dozen pages we are privileged, because of Gwen Lees tape recorder, to hear Philip K. Dick actually composing the plot of his new book, snatching up ideas and trying out characters and conflicts in the crucible of his freewheeling imagination.