MARX AND FREUD

IN LATIN AMERICA

Politics, Psychoanalysis, and Religion

in Times of Terror

BRUNO BOSTEELS

For Lucas Emiliano and Manuel Santiago

In memorium Raf Bosteels (19392012)

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Having been fortunate to be able to present most ideas for this book in graduate seminars, workshops, and public lectures too numerous to mention here, I am grateful to those who invited me to do so and hope that they see at least part of this work as a collective effort.

I want to thank the friends and colleagues who have supported this particular project over the past few years: Etienne Balibar, John Beverley, Sebastian Budgen, Gerardo Caldern, Alejandro Cerletti, Ral J. Cerdeiras, Philippe Cheron, Joshua Clover, Walter Cohen, Jonathan Culler, Pedro Erber, Evodio Escalante, Irene Fenoglio, Federico Finchelstein, Jean Franco, Mara Antonia Garcs, Soren Garca, Carlos Gmez Camarena, Horacio Gonzlez, Mitchell Greenberg, Peter Hallward, Patty Keller, Richard Klein, Stathis Kouvelakis, John Kraniauskas, Nacho Maldonado, Robert March, Frida Mateos, Rodrigo Mier, Alberto Moreiras, Tim Murray, Gabriela Nouzeilles, Edmundo Paz Soltn, Ricardo Piglia, Nelly Richard, Willy Thayer, Alberto Toscano, Miguel Vatter, Geoff Waite, Gareth Williams, and Slavoj iek. Daniel Bensad, Andrea Revueltas, and Len Rozitchner have passed away since I started writing this book, which now has the added function of rendering a modest homage to them. A transatlantic hug also goes out to my entire family in Belgium.

Simone Pinet is the one who made me finish this book, but this should not be held against her. Without her love and intelligence, I am nothing.

In light of what is discussed in them, especially in terms of the rebellion against the father, I dedicate these pages to my sons Lucas Emiliano and Manuel Santiago.

My own father did not live to see this book in print, but his memory will always be with me.

PREFACE

The least that may be said today about Marxism is that, without attenuating prefixes such as post or neo, its mere mention has become an unmistakable sign of obsolescence. Thus, while the old manuals of historical and dialectical materialism from the Soviet Academy of Sciences keep piling up in secondhand bookstores from Mexico City to Tierra del Fuego, almost nobody seems any longer to be referring to Marxism as a vital doctrine of political or historical intervention. Rather, in the eyes of the not-so-silent majority, Marx and Marxism have become things of the past. In the best of all scenarios, they simply constitute an object for nostalgic or academic commemorations; in the worst, they stand accused in the world-historical tribunal of crimes against humanity. Guevarists, Trotskyists, libertarians, revolutionary syndicalists, radical third worldists, and anti-Stalinist communists have all been sent back to the dock to appear before the prosecutors of really-existing capitalism in the great trial of communism, Olivier Besancenot and Michael Lwy write in their recent proposal to retrieve the figure of Ernesto Guevara. This is a trial that places executioners and victims, revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries side by side. Not to accept capitalism is a crime in itself. And while the same fate has not befallen the works of Freud and his followers, even in their case hardly anyone can keep a straight face when remembering the attempts to weld together the Marxist and psychoanalytical notions of praxisrespectively, the political revolution and the talking cureinto a combined Freudo-Marxism.

Not only have the scientific credentials of psychoanalysis come under increasing attack but so too has the idea of an emancipatory potential behind the discovery of the unconscious. Even on purely therapeutic grounds, the virtues of psychoanalysis seem to have been trumped by the pharmaceutical industry. In 1993, Time magazine thus famously was able to put the Viennese doctor on its cover alongside the rhetorical question Is Freud dead? Yet, as Anthony Elliott admonished, Despite the fluctuating fortunes of psychoanalysis, Freuds impact has perhaps never been as far-reaching, albeit now for reasons that are more political than clinical. In a century that has seen totalitarianism, Hiroshima, Auschwitz and the prospect of a nuclear winter, intellectuals have demanded a language able to grapple with cultures unleashing of its unprecedented powers of destruction. Freud has provided that conceptual vocabulary. Beyond providing a far-reaching, if also gloomy, diagnostic of the human condition as well as an intriguing conceptual vocabulary that has penetrated everyday use, however, the question is still very much open as to whether Freuds work might also enable us to envision the radical transformation of our current political situation in ways reminiscent of the promise behind the legacy of Marx and Marxism.

lvaro Garca Linera, the current vice-president of Bolivia under Evo Morales, in an important text from 1996 written from prison, where he was being held in maximum security conditions on charges of subversive and terrorist activitya text titled Three Challenges for Marxism to Face the New Millennium, and included in the collective volume The Arms of Utopia: Heretical Provocations in Marxism describes the situation as follows:

Yesterdays rebels who captivated the poor peasants with the fury of their subversive language, today find themselves at the helm of dazzling private companies and NGOs that continue to ride the martyred backs of the same peasants previously summoned... Russia, China, Poland, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Communist and socialist parties, armed and unarmed vanguards without a soul these days no longer orient any impetus of social redemption nor do they emblematize any commitment to just and fair dissatisfaction; they symbolize a massive historical sham.

With regard to the destiny of Marxs works and the politics associated with them, however, something else appears to be happening as well. The story is not just the usual one of crime, deception, and betrayal. There are whole generations who know little or nothing about those rebels of yesteryear, and much less understand how they would have been able to captivate the impoverished peasants and workers with the fury of their language.

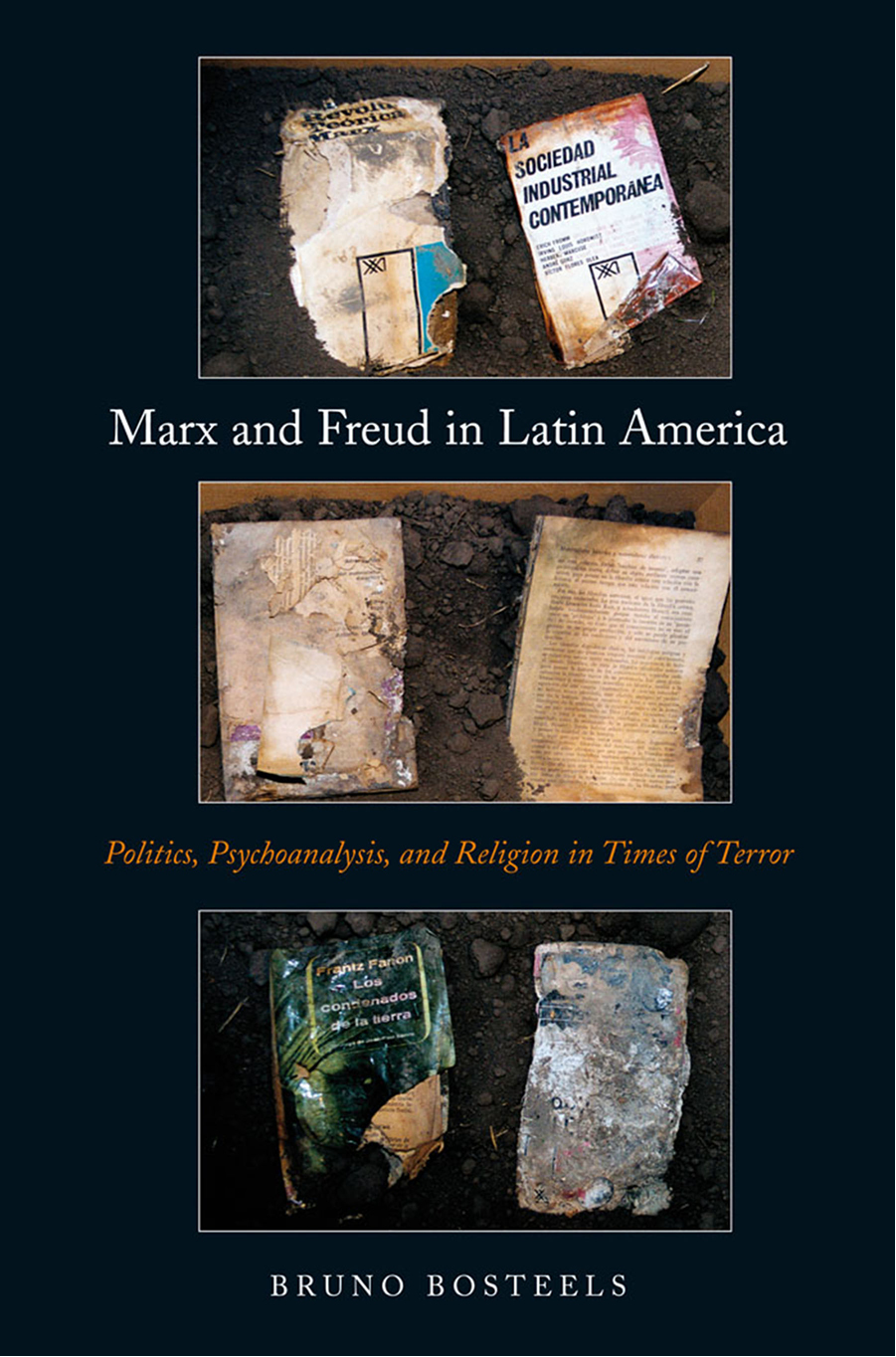

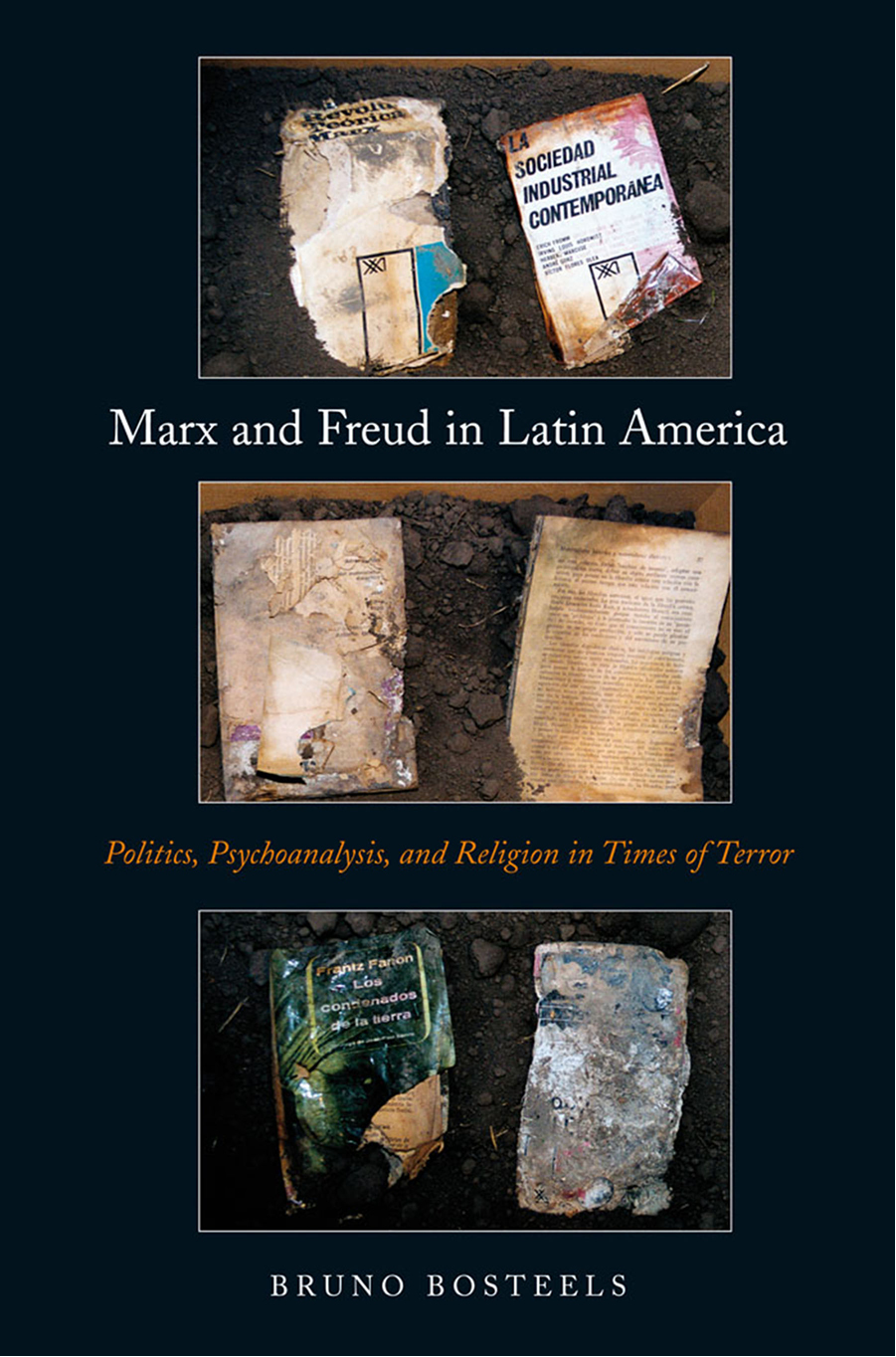

On the one hand, all memory seems to have been broken, and many radical intellectuals and activists from the 1960s and 70sfor a variety of motives that include guilt, shame, the risk of infamy, or purely and simply the fear of ridicule if they were to vindicate their old fidelitiesare accomplices to the oblivion insofar as they refuse to work through, in a quasi-analytical sense of the expression, the internal genealogy of their militant experiences. Thus, the fury of subversion remains, unelaborated, in the drawer of nostalgias, with precious few militants publicly risking the ordeal of self-criticism. What is more, the situation hardly changes if, on the other hand, we are also made privy to the opposite excess, as a wealth of personal testimonies and confessions accumulates in which the inflation of memory seems to be little more than another, more spectacular form of the same forgetfulness. As in the case of the polemic about militancy and violence unleashed in Argentina by the recent epistolary confession of scar del Barco ( No matars : Thou shalt not kill), we certainly are treated to a heated debate, but what still remains partially hidden from view is the politico-theoretical archive and everything that might be contained therein, in terms of relevant materials for rethinking the effective legacy of Marx and Marxism in Latin America. And we could argue that the same is true, though with less spectacular effect because oblivion also has been more spontaneous, of that strange hybrid of Freudo-Marxism in Latin America.

Next page