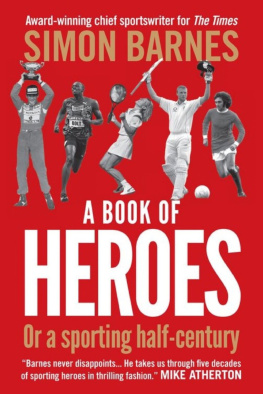

M.J.K. SMITH OF WARWICKSHIRE and England was my first hero. To this day I have no real idea why. After all, he was never a great cricketer. The election just fell on him. He was there when a vacuum needed to be filled. It certainly wasnt because I saw him as a superman. Right from the first, I was aware of his fallibility: and his every failure caused me a strange, subtle pain. Perhaps the reason I chose Smith perhaps the reason anybody chooses anybody as a hero is to know pain. To understand failure. To know sadness. To come to terms with the worlds imperfections.

I used to go to the cricket at Edgbaston with my grandfather, day after day of endless sunlit summers, catching the bus at the top of Vicarage Road, Kings Heath with our sandwiches neatly parcelled in my grandfathers leather valise. I was about eight when we started. Of course, all the cricketers we saw on those perfect days days without the least scintilla of boredom were heroes of a kind: giants in white clothing with an elevated calling, living the brave life in pursuit of runs and wickets and glory, men to whom self-doubt was a stranger.

Smith was their captain: captain of Warwickshire, going on to become captain of England. Thats why he had an asterisk before his name. Perhaps it was the asterisk that caused me to single him out: I felt under an obligation to throw in my lot with a person so obviously selected for me. But Smith was not an imposing figure, nor, it must be said, particularly successful. He wore wire-framed glasses that tried to be invisible but failed. These, combined with an awkward smile, made him different from the sculpted stars of Tiger comic.

But he was my hero, all the same. Not because I overrated him: but because I had chosen him. I didnt try to be like him. I didnt think he was a god. I didnt think he was better than everybody else: I just hoped it would turn out that way. Some mysterious process had made him my representative. As a result of this, his successes were my successes: his failures mine.

The notion of the hero has been debased, especially in sport. The term has come to imply uncritical admiration, even worship. It tends to mean role model, a hideous term, one that seems to insist that it is a childs duty to be as much like his hero as possible: willingly losing his identity in the profound need to be someone else. This is not a legitimate process: it is a personality disorder. And I dont think it actually happens to anyone without a personality disorder: the lie of the role model is a convention that sport, forever puffed up with pride, has invented to boost its own glory. The truth is that a hero is someone who helps you to understand life: helps you to understand how better to enjoy life, and how better to endure it. That is as true of heroes in sport as it is of heroes in fiction and mythology, and it is why heroes matter throughout our lives. Heroes play a large part in the life of a child, but they continue to matter as we grow up, in ways that constantly change and develop. A grown-ups hero is very different from the heroes of children and adolescents, because we slowly learn that heroes and heroism are far more complex than we had supposed. Take Oedipus, for example. Oedipus is a hero all right. He is the hero of his own myth, and of the plays written about him. Oedipus tells us many difficult and profound things. Oedipus matters. But no one has suggested that Oedipus given to road rage, lechery, power-mania and self-harm is a role model. He is a much more complex figure than that: and so, for that matter, was M.J.K. Smith. So are all other heroes, and so are the relationships we have with them: vivid, intense, revealing, often painful and of course, more or less by definition, one-sided.

Smith was nearly great. There is glory in this: also a whiff of tragedy. He was one hell of a games player. He was the last of the double internationals, if you restrict the definition to major sports and reckon it by the date of the last appearance for England. He played one rugby match for England, against Wales in 1956; he played 50 times for the England cricket team, 25 of them as captain, last appearing in 1972. He was a batsman who rebelled against the classical technique of offside strokeplay and hit the ball the other way, to leg, to what he called the mans side. He would fetch the ball from outside off-stump with pulls and sweeps: a technique that became a new orthodoxy as the game changed. Smith was both a throwback, then, and a man ahead of his time. He was good, too: in 1959, he scored 3,249 runs in the first-class cricket season, unthinkable now. He made more than 2,000 runs in six consecutive seasons. He liked to field close and courageous at short-leg: I remember him plucking the ball right off the face of the bat, plunging to the ground to astonished gasps from the crowd yes, a throwback indeed, for there were always crowds when my grandfather and I went to county cricket.

So there was much to admire. I used to steal the daily paper from my parents and scan the county cricket scoreboards, as inky-fingered boys had done for generations, and, like them, I found a brief taste of heaven or hell in what I found there as I looked for Warwickshire, and for *M.J.K. Smith. He let me down, though, far too often. He let me down cruelly. I would note with dismay that he always seemed to score a century in matches that didnt matter, picnic occasions like Gentlemen v Players, the now obsolete fixture in which amateurs played the professionals in a genteel extension of the class war.

Smith had a devastating run of low scores in the 60s, vulnerable against pace at the start of an innings like so many other nearly-but-not-quiters. It saddened me that the heroes of my friends always did better than M.J.K. I was walking round the school playing field one day with my friends Stuart Barnett and Ian Hart, listening to the cricket on the radio. The year was 1965. England were playing New Zealand. Smith came out to bat, and was out for a duck, lbw to Richard Collinge. A captains innings! Stuart mocked. Stuart was cruel; but then life is cruel, and so is sport. If it wasnt cruel, we wouldnt watch it. And if heroes didnt have the capacity to cause us pain, we wouldnt bother with them. I rather think I knew that then, but it wasnt much consolation.

YOU ARE TOLD NEVER to meet your heroes. Such nonsense. Of course you should meet your heroes, if only for the disappointment. And anyway, I wasnt disappointed when I met Anita Lonsbrough, 44 years after I became aware of her heroic existence. I had been on nodding and halloing terms with her for some years before that, but I first had a proper conversation with her in Athens in 2004. She looked great: a statuesque lady of a certain age. She held herself beautifully: youd know her at once as a former athlete if you had your wits about you. I was with my colleague from