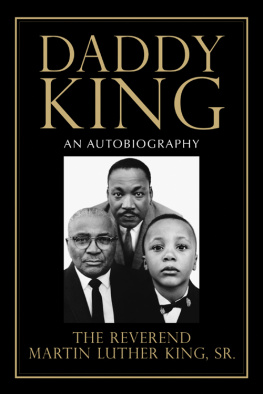

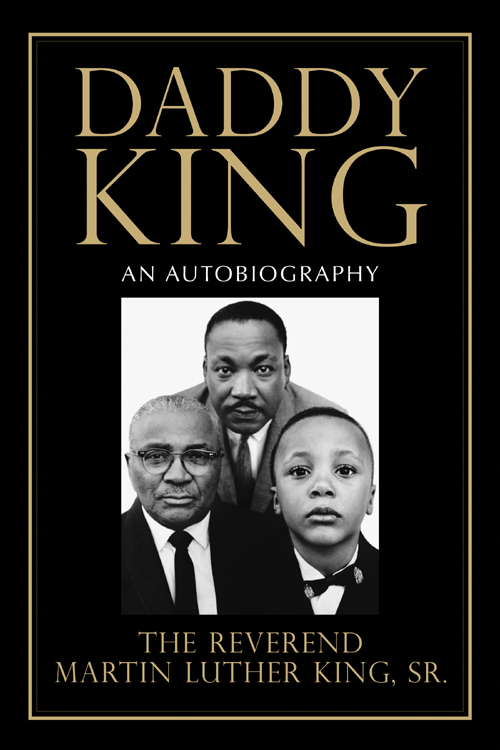

This book is dedicated to the memory of my wife, Alberta Christine Williams King; my sons, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Alfred Daniel Williams King; and my granddaughter, Esther Darlene King. It is also dedicated to my daughter, Christine King Farris; my grandchildren, Alveda King Beal, Yolanda Denise King, Alfred Daniel Williams King II, Derek Barber King, Martin Luther King III, Vernon Christopher King, Dexter Scott King, Isaac Newton Farris, Jr., Bernice Albertine King, Angela Christine Farris; and my great-grandchildren, Jarrett Reynard Ellis, Eddie Clifford Beal III, and Darlene Ruth Celeste Beal.

From the days of our courtship until her tragic death on June 30, 1974, my wife was the quiet courage by my side in all of my endeavors. My sons, whose works have spoken for themselves, moved with courage to do what they knew was right. My daughter, Christine, has worked with the legacy of her mothers quiet courage and her own strengths to make her statement in the tradition of the values which we instilled in her.

My grandchildren, who range from a Georgia State Representative to a high school junior, have brought me untold hours of joy and happiness in their quests for the meaning of their own lives. They are the New South for which I have worked since the days of my youth.

Finally, this book is dedicated to my great-grandchildren, on whom the mantle will fall to continue the legacy of their ancestors.

GRANDDADDY

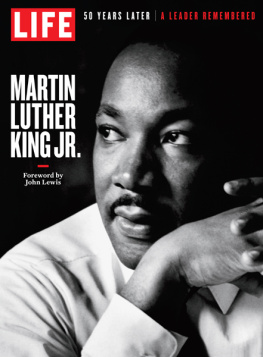

Foreword to the 2017 Edition

The world knew him formally as the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Sr. Many knew him affectionately as Daddy King. I knew him simply as granddaddy, but all who were acquainted with his presence respected this influential man of God. As new generations of Americans become familiar with the life of my grandfather, they will better appreciate how my uncle, his son, Martin Luther King, Jr., evolved into one of the most influential leaders of the twentieth century. In fact throughout my uncles life, my grandfather played a key role in allowing my uncle to retain the financial and political independence necessary for him to be at all times an uncompromised public servant. His life story is the traditional American narrativestarting with nothing but through hard work achieving somethingbut his story is made extraordinary when one factors in that my grandfather was the traditional second-generation descendent of American slaves, born to parents who were sharecroppers in the race-discriminating rural Southern town of Stockbridge, Georgia. In the midst of this hopelessness, his will to succeed and the call he felt to the ministry caused him to rise above his circumstances and not only achieve a successful life but give the world one of its greatest leaders. In his case, the saying of hands that picked cotton now pick presidents rings particularly true, as former president Jimmy Carter would attest to, because of the game-changing intervention my grandfather made in his 1976 presidential campaign. It is no coincidence that the greatest theologian of the twentieth century shares the name of the greatest theologian of the sixteenth century. Michael King was my grandfathers original name, and Michael King, Jr., was the birth name of my uncle, but after traveling to Europe as a young Christian minister and learning of the philosophy and the protest reformation of the Christian church by Martin Luther, my grandfather returned to America and changed his name to Martin Luther King, Sr., and changed my uncles name to Martin Luther King, Jr., proof positive of the vision he held of himself and the vision he would plant inside his namesake son. Long before the historic 1963 March on Washington, Martin King, Jr., saw his father lead a march on Atlanta City Hall to protest separate water fountains for black and white citizens. This bold act in the late 1930s was as provocative and a million times more life threatening than any march in the nations capital would ever be. King, Sr., led the successful protest and legal fight to equalize the pay of black and white teachers of the Atlanta public schools. This would cause the Atlanta Board of Education to deny his daughter, Dr. Christine King Farris, a Spelman graduate and a holder of two master degrees from Columbia University, employment as a teacher until the intervention of then mayor William B. Hartsfield. But, like my uncle, first and foremost my grandfather was not a social activist but a man of God who provided forty-four years of devoted pastoral leadership to the parishioners of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, and, last but not least, he was GRANDDADDY , a man who would deny his grandchildren nothing and moved heaven and earth to help us achieve our goals. He was the paradigm of our familys morals and beliefsfaith in God, strength, courage, charity, sacrifice, and determination. He was the solid-rock foundation we all stood on, the one who provided the ultimate sense of security for us all. His life story is truly one for the ages and an example of how America at the low point of mistreatment of its darker-hued citizens still produced a remarkable American original such as MARTIN LUTHER KING, SR .

I SAAC N EWTON F ARRIS , J R.

FOREWORD TO THE 1980 EDITION

Martin Luther King, Sr., was born free, free as the wind that blows, free as the birds that fly. Let me prove this assertion:

At Stockbridge, Georgia, at the time, a Negro was not born human but was born a Negroand a Negro meant that you were inferior and had no rights that the white man had to respect. Daddy King, as he is affectionately called, was born in Stockbridge, a few miles from Atlanta, in 1899. At fourteen, Daddy King left Stockbridge and went to Atlanta and got a job as a fireman on the railroad. The train went through Stockbridge, and he told his mother that when he went through the town he would blow the whistle. His mother did not want her son to be on the railroad, so she visited the Southern Railroad officials and told them that her son had put his age up and that he was not of age to be working. They let Daddy King go.

In those days, a dishonest landownerand there were manycheated his tenants. In renting land, the first bales of cotton ginned, whether two, three, or four bales, went to the owner, but the cottonseed money went to the renter. Young Kings father was cheated. The boy heard the owner tell his father that he had broken even and was out of debt. Young King said to his father, Ask him about the cottonseed money, Daddy! The boss, incensed over this young black participating in his fathers business, told young King to shut up. Kings father told Martin Luther to keep quiet and go away. Kings father had kept an account of what he spent and he was comparing his figures with the owners figures. The white owner insisted that his figures were right. Young King hollered out, Daddy, ask him about the cotton-seed money! This was a courageous thing for a young black boy to do in Stockbridge around the close of the nineteenth century.

Another incident is worth noting. One day Kings mother sent him on an errand in Stockbridge. A white man interfered with the errand. He wanted young Martin Luther King to do something else, but the boy refused. In those days, a Negro was to do what a white man told him to do. For this refusal, the man beat Martin Luther. When Martin Luther got home, he told his mother what the white man did to him, and she went to the white man and beat him up. If this isnt a sign of freedom in the parents of Daddy King, I dont know what freedom is. This is from Kings side of the family.