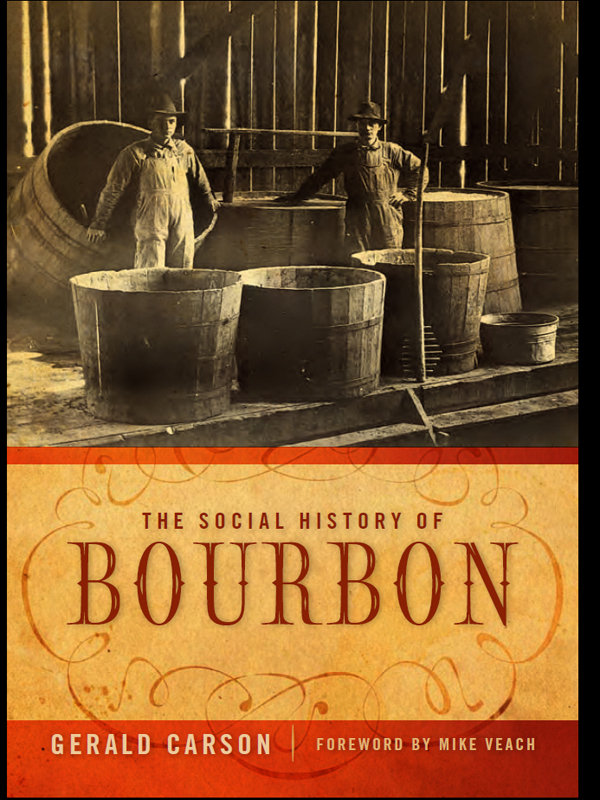

The Social History

of Bourbon

GERALD CARSON

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY

Copyright 1963 by Gerald Carson

Paperback edition 2010 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Carson, Gerald.

The social history of bourbon.

Reprint. Originally published: New York: Dodd, Mead, 1963.

Includes index.

1. WhiskeyKentuckyHistory. I. Title.

TP605.C3 1984 394.1'3 84-2216

ISBN 978-0-8131-2656-2

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of

American University Presses

For Lettie

Why should not our countrymen have a national beverage?

Harrison Hall, The Distiller

Philadelphia : 1813

Contents

Foreword to the

New Edition

The Social History of Bourbon is the first scholarly examination of the distilling industry in the United States. When Carson wrote it in the early 1960s, Prohibition was still part of the living memory of many Americans, and the bourbon industry was enjoying a strong market. In his own way, Carson was exploring a new frontier.

More than just a history of distillers, The Social History of Bourbon is the story of the saloon and the impetus to close down this uniquely American institution. Carson recognizes that Prohibition, on the surface a movement to stop the drinking of alcohol, was at the same time a reaction to social issues such as the flood of new immigrants to the United States and a commensurate growing political clout of urban areas. The saloon was a not insignificant feature of these social phenomena, as a place where new arrivals in American cities could gather, where politicians could build voting blocks, and where good, decent family men might be led astray by vices associated with drinking such as gambling and prostitution. By connecting saloons with various burgeoning social malaises, or with cultural trends that made Americans uneasy about holding on to their traditional ways of life, Prohibitionists gathered more supporters than by simply presenting the deleterious effects of alcohol consumption. In this sense, the book is as much about the saloon as it is about bourbon.

Carson begins his historical narrative by placing the drinking of spirits in the context of the earliest days of American history. He examines the relationship of the slave trade to New England rum, the first spirit to play an important role in the American economy. It was only due to the decline and eventual demise of the slave trade that whiskey surpassed rum production among American distillers. Several early distillers in Kentucky, any one of which could have been credited with creating bourbon whiskey, are examined in some detail. Carson gives a reluctant nod to Elijah Craig as the inventor of bourbon, perhaps in part because Carson was amused by the notion of a distiller who is at the same time a man of Goda Baptist preacher. The final chapters of the book address the early twentieth century, including President Taft's decision to define whiskey, whiskey stories and folklore, and whiskey in the post-Prohibition world. It is almost as if Carson prefers the pre-Prohibition world to the regulated and safe world of modern bourbon production.

At the time Carson wrote The Social History of Bourbon, the bourbon industry was led by people who remembered Prohibition and even some who could recall the days prior to Prohibition. Carson took advantage of their knowledge in the writing of this book, but his reliance on these sources sometimes inadvertently introduces misinformation. It can be disputed, for example, whether Old Forester is named for Nathan Bedford Forrest, or whether James E. Pepper introduced the Old Fashioned cocktail to New York City. Still, the breadth of the chapter notes, in combination with Carson's research at The Filson Historical Society, the Kentucky Historical Society, the Library of Congress, and the Chicago Historical Society, among others, stands as testament to his diligent and extensive scholarly research.

One historical event about which Carson is dead-on is the Whiskey Rebellion. He does not perpetuate the myth of the rebels fleeing to Kentucky but rather states that they left the jurisdiction of the federal marshals by fleeing to Spanish Louisiana. A distiller wanted by federal marshals in, say, western Pennsylvania would still be in the jurisdiction of the marshals if he fled to the state of Kentucky or even the northwest territories of Ohio, Indiana, or

There are some facts that Carson simply gets wrong, especially where he depends on distilleries for information. For example, he states that Old Forester Bourbon was named for Confederate general Nathan B. Forrest. This was the story used by Brown-Forman Distillery at the centennial of the American Civil War. Clearly, the distillery found it advantageous to tie its product to a famous Civil War general. Brown-Forman's own records show, however, that the brand was named for Louisville physician Dr. William Forresteralso a veteran of the Civil War, but not as prominent as General Forrest. There are other examples of incorrect information in the book, and the reader should be aware of this problem and be prepared to do further research.