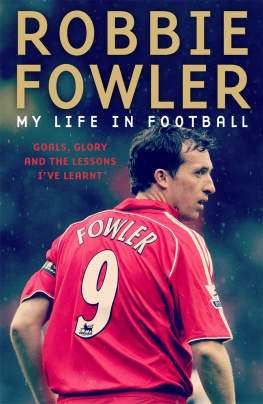

For Mariana, Georgina and Lucas. Im proud of my professional achievements, but nothing could make me more proud than our family

I am a lucky man. Ive got a wife I adore and two children I dote on. I have a loving father and two sisters of whom Im very proud. Once, I had a mother who doted on me. Ive got a good life and a lovely house and I know I have an awful lot to be thankful for. I owe my material possessions to my career in football. The opportunities that are coming my way in the media and in business now also stem from the fact that I was a high-profile sportsman. And Im proud of the links I still have with Chelsea and the ambassadorial role I have been asked to fulfil for them. I have every reason to be grateful to the game for the things it has brought me, but it hasnt come easy. I was a man apart for much of my career. I came out of left field and, for a long time, I stayed there.

I was regarded as an irritating curiosity when I first signed as a professional footballer with Chelsea in late 1987. I was ridiculed for reading The Guardian rather than staring at the half-naked women on page 3 or raging at the stories on the back pages of the tabloids that the players reading them swore were lies. But they kept reading them. Partly because of me, partly because of them, I didnt fit in. Partly because of an experience that had affected me in Jersey when I was thirteen, there was an urge to succeed inside me that made me more sensitive than I might otherwise have been. I was coming out of left field, a callow kid raised in the Channel Islands who knew nothing of the wider world, and most people didnt know quite what to make of me.

Because I had different interests to the rest of my team-mates, because I didnt feel comfortable in the pre-Loaded laddish drinking culture that was prevalent in English football in the late Eighties, it was generally assumed by my team-mates that there was something wrong with me. It followed from that, naturally, that I must be gay. For fourteen years, I had to listen to that suggestion repeated in vivid and forthright terms from thousands of voices in the stands. I seemed to be everybodys favourite whipping boy.

My colleague at Stamford Bridge, Graham Stuart, who had a fine career with Chelsea, Everton and Charlton, says now that I was ahead of my time when we played for Bobby Campbell in the late Eighties. Off the pitch, he meant, obviously a renaissance footballer in a dark age. Well, I was certainly in a minority. He was right about that. I just liked different things, ironically the kind of things footballers like now: a nice meal, an afternoons shopping, a trip to the cinema or a gig at The Fridge in Brixton, getting ready for the next game, feeling the intensity of a life in sport. Now, the traditional English approach I grew up with, where men were men and only women wore sarongs and used moisturizer, has been completely shattered. The pendulum has swung. Its more acceptable for players to talk about the clothes they wear, the restaurants they frequent, the bars they go to. And, yes, the latest game for their PlayStation or the latest innovation on their iPod.

It would have been easier for me back in the early days if I could have found it inside me to subordinate my personality to the group and do what it took to blend in. But I was taking care of my diet when the team coach was still stopping at the fish and chip shop on the way back from away matches. I was hanging out at an Armenian caf called Jakobs in Gloucester Road in west London while The Lads were organizing pub crawls. Again, it wasnt that one was better than the other. Jakobs wouldnt be everyones idea of fun; I know that. But I liked it. It was just that I fell out of their norm. As far as the culture off the pitch was concerned, I pitched up ten years too early.

My Chelsea career spanned different worlds. I started it playing with Kerry Dixon, Steve Wicks and John McNaught. I ended it alongside Marcel Desailly, Gianfranco Zola and Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink. I gravitated towards the couple of foreign lads at the club in my first spell and people called me a homosexual. I gravitated towards the mass of foreign lads at the club in my second spell and people called me cosmopolitan.

That was the funny thing about my life in football, the theme that runs through it. Football began to move towards me; events conspired to help me. In 1995, when I was winning the Premiership title with Blackburn Rovers, the Bosman ruling came into force and changed the face of the game in this country. Bosman swept away the quota system that had limited the number of foreigners allowed to play in each team and, flooded by players from all over Europe, our game entered an age of enlightenment.

I wasnt an outsider any more; I wasnt perceived as being different. Football old-schoolers like former Chelsea captains Peter Nicholas and Graham Roberts, who had regarded me as a dork, a swot and a pretentious weirdo, didnt hold sway any more. Traditional bastions of English football clubs men who ruled by intimidation and bullying began to be marginalized, and a culture that rewarded professionalism, instead of pouring scorn on it, took hold.

There were more changes in the three decades in which I played football in England than there have been in any other era of the game. The horrors of Heysel and Hillsborough were washed away by Gazzas tears in the 1990 World Cup and the football boom that Englands run to the semi-finals in Italy engendered. The Fever Pitch generation rose up in the Nineties and suddenly it was trendy to be a football obsessive. There was the Britpop influence, too. A lot of the successful bands of the Nineties were made up of football fans who were always making reference to the sport they loved. I was friends with one of the lads in the Inspiral Carpets who was an Oldham fan, Noel and Liam Gallagher were Man City fans and Tim Booth from James was a Leeds fan. Together, they crossed the musicstudentfootball divide and broadened the appeal of the game. The Lightning Seeds did the theme tune for Euro 96 and the separation between footballers and pop stars became more and more blurred. The Taylor Report forced football stadia into a brave new world, too, and when the Premier League was formed in 1992 and soon flooded with money from Sky TV, it made players into millionaires pretty much overnight.

I was part of that; I rode the wave. I went from an era when people like Ken Bates, David Moores and Doug Ellis owned football clubs to the age of Roman Abramovich and the invasion of the international oligarchs. I played for the only team apart from Manchester United, Arsenal and Chelsea who has ever won the Premiership. I played thirty-six times for England. I didnt get carried away with it. I never lost my obsession with winning and my hunger to keep moving forward as a player. I was relentless about it. I never looked back. I didnt like looking back not after what had happened to my mum.

It wasnt as if I had it easy, either. For a start, I had people chanting Le Saux takes it up the arse wherever I played. What an incentive that was never to make a mistake. Even in the winter of my career, playing for Southampton in a reserve game against West Ham at Upton Park, this young kid in the West Ham side started yelling abuse at me, spitting faggot and queer at me. I told him that when hed achieved what Id achieved in the game, he could come back and talk to me. At half-time, I heard him getting a bollocking from West Hams reserve team boss.

I enjoyed highs and I saw lows. I heard the snap of Robbie di Matteos leg breaking in Chelseas UEFA Cup match against St Gallen. When Pierluigi Casiraghis career came to a terrible end at West Ham, I ran off the pitch and grabbed the stretcher from the St Johns Ambulance men who were standing in the tunnel while he was in agony on the floor with terrible injuries to his leg. I saw the grief and the pain that football can bring as well as the riches and the glamour. I saw the last snapshot of Chelsea before the revolution: its extravagance cheek by jowl with its miserliness, and the fantastic idiosyncrasies of the Ken Bates era. I was man of the match in the game that took Chelsea into the Champions League and made it viable for Abramovich to buy them.

Next page

![Graeme Stuart [Graeme Stuart] - Introducing JavaScript Game Development : Build a 2D Game from the Ground Up](/uploads/posts/book/121400/thumbs/graeme-stuart-graeme-stuart-introducing.jpg)