In memory ofJonas MekasPoet, filmmaker, intellectual19222019 Contents It seems like yesterday, but Edge has been up and running for twenty-two years. Twenty-two years in which it has channeled a fast-flowing river of ideas from the academic world to the intellectually curious public. The range of topics runs from the cosmos to the mind, and every piece allows the reader at least a glimpse and often a serious look at the intellectual world of a thought leader in a dynamic field of science. Presenting challenging thoughts and facts in jargon-free language has also globalized the trade of ideas across scientific disciplines. Edge is a site where anyone can learn, and no one can be bored. The statistics are awesome: the Edge conversation is a manuscript of close to 10 million words, with nearly 1,000 contributors whose work and ideas are presented in more than 350 hours of video, 750 transcribed conversations, and thousands of brief essays.

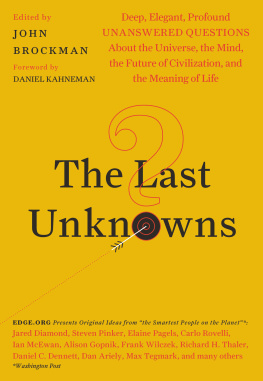

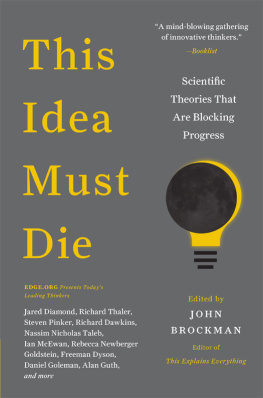

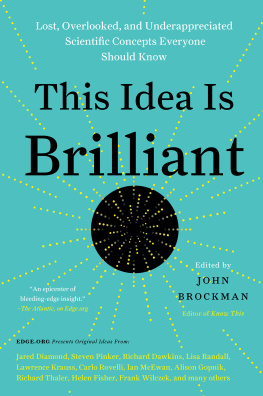

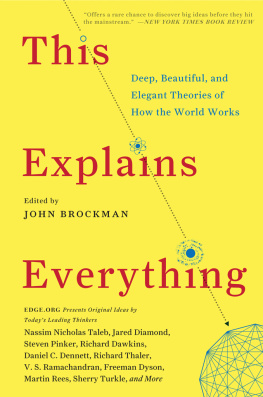

And these activities have resulted in the publication of 19 printed volumes of short essays and lectures in English and in foreign language editions throughout the world. The public response has been equally impressive: Edges influence is evident in its Google Page Rank of 8, the same as The Atlantic, The Economist, The New Yorker, and the Washington Post; in the enthusiastic reviews in major general-interest outlets; and in the more than 700,000 books sold. Of course, none of this would have been possible without the increasingly eager participation of scientists in the Edge enterprise. And a surprise: brilliant scientists can also write brilliantly! Answering the Edge question evidently became part of the annual schedule of many major figures in diverse fields of research, and the steadily growing number of responses is another measure of the growing influence of the Edge phenomenon. Is now the right time to stop? Many readers and writers will miss further installments of the annual Edge questionthey should be on the lookout for the next form in which the Edge spirit will manifest itself. What is the secret of Edges success? To begin with, the charisma of John Brockman, its founder and leader.

Add to that his eclectic but discerning taste in the choice of participants. The two major formats of Edge activities are no less important. The interviews are edited to make the interviewer invisible. Masking the questioner is not new, but remarkable skill is required to elicit both clarity and depth in seamless expositions of the participants ideas. Edge interviews read and sound like coherently constructed informal lecturesa surprising feat when the flow of the content is entirely driven by the interviewers questions. The short-essay format of the Edge Annual Question is a daring innovation and a striking success.

Apparently, 6001,000 words is the sweet spot for introducing one big idea. The brevity disciplines the author and allows the reader to grasp the essential pointand to remain hungry for more even as she moves to another essay. The unifying message in the story of Edge is that ideas matter, and they matter to many. They can be told with elegance, sometimes with wit, never with condescension. There is a large audience eager to learn what scientists in various disciplines are up to, and a large group of scientist-teachers eager to tell their stories. And certainly, there will be more stories.

Daniel Kahneman New York City

After twenty years, Ive run out of questions. So, for the finale to a noteworthy Edge

project, can you ask The Last Question? Did I say twenty years? My strange obsession with the idea of Question goes back to 1968, when I first wrote about the idea of interrogating reality: The final elegance: assuming, asking the question. No answers. No explanations. Why do you demand explanations? If they are given, you will once more be facing a terminus. They cannot get you any further than you are at present.

The solution: not an explanation: a description and knowing how to consider it. Everything has been explained. There is nothing left to consider. The explanation can no longer be treated as a definition. The question: a description. The answer: not explanation, but a description and knowing how to consider it.

Asking or telling: there isnt any difference. No explanation, no solution, but consideration of the question. Every proposition proposing a fact must in its complete analysis propose the general character of the universe required for the fact. Our kind of innovation consists not in the answers, but in the true novelty of the questions themselves; in the statement of problems, not in their solutions. A total synthesis of all human knowledge will not result in huge libraries filled with books, in fantastic amounts of data stored on servers. Theres no value any more in amount, in quantity, in explanation.

For a total synthesis of human knowledge, use the interrogative. The conceptual artist/philosopher James Lee Byars contacted me and suggested a collaboration of sorts which resulted in our taking daily walks in Central Park as Byars and I walked and talked, conversing only in interrogative sentences. Does it sound like fun? Want to try it? James Lee soon began to develop his ideas, which led to The World Question Center: To arrive at an axiology of the worlds knowledge, seek out the most complex and sophisticated minds, put them in a room together, and have them ask each other the questions they are asking themselves. On November 26, 1968, he launched The World Question Center in a one-hour television program produced in Brussels at the studios of the Belgian national television network and broadcast live to a national audience. During the hour, he called numerous celebrated intellectuals such as composer John Cage, science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, futurist Herman Kahn, artist Joseph Beuys, novelist Jerzy Kosinski, poet Michael McClure, and asked, in various ways, the following: Im trying to find hypotheses that people are working with that are reduced into some type of very simple single question with no explanation, hopefully, thats important to them in their own evolution of knowledge.

Might you offer one thats personal? For the 50th anniversary of The World Question Center, and for the finale to the twenty years of Edge Questions, I turned it over to the Edgies: Ask The Last Question, your last question, the question for which you will be remembered. John Brockman Editor, Edge Can we program a computer to find a 10,000-bit string that encodes more actionable wisdom than any human has ever expressed? SCOTT AARONSON David J. Bruton Centennial Professor of Computer Science, University of Texas at Austin; author, Quantum Computing Since Democritus Are complex biological neural systems fundamentally unpredictable? ANTHONY AGUIRRE Professor of physics, University of California, Santa Cruz Are the simplest bits of information in the brain stored at the level of the neuron? DORSA AMIR Postdoctoral research fellow, Boston College Are people who cheat vital to driving progress in human societies? ALUN ANDERSON Senior consultant (and former editor-in-chief and publishing director), New Scientist; author, After the Ice How can we put rational prices on human lives without becoming inhuman? CHRIS ANDERSON Chief executive officer, 3D Robotics; founder, DIY Drones How will we build the tools to maintain the software in long-lived online devices that can kill us? ROSS ANDERSON Professor of security engineering, University of Cambridge How do we best build a civilization that is galvanized by long-term thinking? SAMUEL ARBESMAN Complexity scientist; scientist in residence, Lux Capital; author, Overcomplicated

Next page