THE BOOK OF DEDE KORKUT

GEOFFREY LEWIS was born in London in 1920 and studied Classics at St Johns College, Oxford. His studies were interrupted by the Second World War, during which he served for five years as a radar operator in the RAF, mainly in Egypt and Libya. On returning to Oxford, he read Arabic and Persian and taught himself Turkish. In 1950 he was awarded a doctorate and became a lecturer in Turkish, later rising to the position of Professor. He was chiefly responsible for the establishment of Turkish studies at Oxford, where his teaching interests ranged from the earliest Orkhon inscriptions to modern Turkish poetry. His book Teach Yourself Turkish (1953, revised 1989) is still the classic introduction to the language. Geoffrey Lewis retired in 1987 and died in 2008.

Translated and introduced by

GEOFFREY LEWIS

The Book of Dede Korkut

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London, WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

This translation first published in Penguin Books 1974

Published in Penguin Classics 2011

Translation and editorial material Geoffrey Lewis, 1974

All rights reserved

The moral right of the translator has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-241-96086-8

FOR LALLY AND JOB

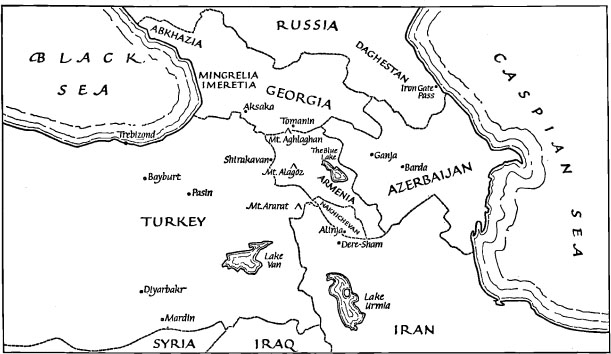

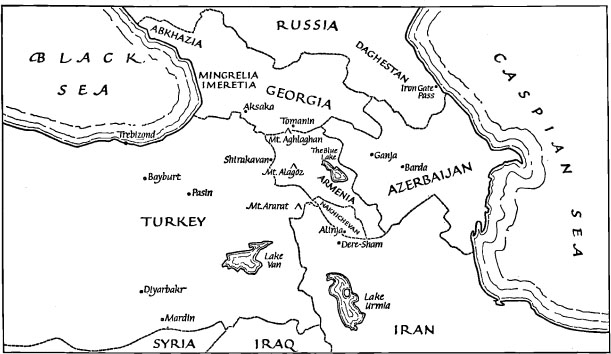

Principal places mentioned in the text and notes. The political boundaries are modern.

Introduction

T HE B OOK OF D EDE K ORKUT is a collection of twelve stories set in the heroic age of the Oghuz Turks. The oldest monuments of written Turkish are the inscriptions found in Siberia and Mongolia, the earliest dating from the eighth century AD. In these, Oghuz and Turks appear as the names of two distinct communities, sometimes at war with each other, sometimes in an alliance in which the Turks are the dominant partner. Later, however, the Oghuz are referred to as a Turkish tribe (for example, by Mahmud Kashghari, the eleventh-century lexicographer); this is because the name Turk, originally applied to the most powerful segment of the people, was subsequently applied to the whole people.

In the ninth and tenth centuries, the Oghuz migrated westward, from the region of the Altai Mountains and Lake Baikal, to the lands between the Syr Darya and Amu Darya (Jaxartes and Oxus) and east of the Caspian. In their new home, they came under the influence of Islam, for this land was within the dominions of the Arab Caliphs of Baghdad. Still moving westward, the Islamicized Oghuz formed the bulk of the forces led by the family of Seljuk, who conquered Iran in the eleventh century and Anatolia in the eleventh and twelfth. The Ottoman dynasty, who gradually took over Anatolia after the fall of the Seljuks, towards the end of the thirteenth century, led an army that was also predominantly Oghuz.

It is clear that the stories were put into their present form at a time when the Turks of Oghuz descent no longer thought of themselves as Oghuz. So in : In the days of the Oghuz there was a stout-hearted warrior called Kanli Koja. Now it is known that the term Oghuz was gradually supplanted among the Turks themselves by Turkmen, Turcoman, from the mid tenth century on, a process which was completed by the beginning of the thirteenth. The Turcomans were those Turks, mostly but not exclusively Oghuz, who had embraced Islam and begun to lead a more sedentary life than their forefathers (although it must be noted that the evidence is not unequivocal and that the modern Turcoman tribes are still largely nomadic). We may therefore suppose that the stories were given their present form after the beginning of the thirteenth century. But there is no possible doubt that the basic material of the stories is far older.

The Oghuz in the stories live off their flocks and herds, and the whole tribe migrates from summer-pasture to winter-quarters and back. The society depicted is aristocratic. At the head of the Oghuz is the Great Khan, Bayindir, though he tends to remain in the background, the control of affairs being in the hands of his son-in-law Salur Kazan. With only two notable exceptions, commoners do not play much of a part; a shepherd fathers the monster Goggle-eye .in to the ladies laughing behind their yashmaks, especially in view of what is said there about the behaviour of two of the ladies.

The houses in which the heroes and heroines live are tents, of the type used by the modern Turcoman tribes; they are made of felt, laid over a wooden frame in the shape of a beehive. The tents in the stories are splendid and ornate, as befits their heroic occupants; the very smoke-holes are described as golden, presumably meaning that they were surrounded by a golden frame.

Although the stories have been given an Islamic colouring, they are full of references to the most ancient practices, some going back to the time when the religion of the Turks was shamanist. On the death of a hero, his relatives slaughter his horses and give a funeral feast () asks for his horses tail to be cut off. A boy is not given a name until he has distinguished himself in battle. The antiquity of this last practice is shown by the occurrence in the old inscriptions of such statements as my manhood-name is Yaruk Tegin and my young brothers manhood-name became Kl Tegin. When the characters are distressed they weep bloody tears; this is not entirely metaphorical, for at Turkish funerals in ancient times the mourners would gash their faces and let the blood mingle with their tears.

Not much perspicacity is required to see that the Islamic colouring has been superimposed on stories that are basically pre-Islamic. The enemy throughout is equated with the infidel, , include the line When the long-bearded Persian calls to prayer. Although this shows that the Turks were not strangers to Islam when this line was composed, it also shows that they were as yet only newcomers to it.

Dede Korkut, after whom the book is named, is the soothsayer, high priest and bard (ozan) of the Oghuz. Dade (Grandfather) is still heard in Turkey as a title of popular saints and holy men. It is he who gives the young men their names when they have proved themselves, it is to him that the Oghuz turn in time of trouble, for advice and practical help. At the gatherings of the Oghuz he plays his lute (