The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Anthea Morrison

Acknowledgements

For help, advice and information of various kinds, I must thank the Cambridgeshire Beekeepers Association, Julian Barnes, Catherine Blyth, Caroline Boileau, the British Library, Jeremy Burbidge, Stephen Butterfill, Cambridge University Library, Lauren Carleton Paget, Geoffrey Chepiga, Helen Cloughley, Laurie Croft, Santanu Das, Bob Davenport, Alan Davidson, Jane Davidson, Tamasin Day-Lewis, Katherine Duncan-Jones, Richard Duncan-Jones, Fuchsia Dunlop, Sam Evans, Robin Glasscock, Nico Green, Rob Green, Christopher Hawtree, Rose Hilder, Tristram Hunt, the International Bee Research Association (IBRA), Jacqueline de Jong, Andy Joyce, Thomas King at DC Comics, Dominic Lawson, Peter Linehan, Angus MacKinnon, Anne Malcolm, Laura Mason, the Maison du Miel, Anthea Morrison, The National Honey Show, Mark Nichols, Northern Bee Books, Cristina Odone, Charles Perry, Roland Philipps, Bonnie Pierson, Elfreda Pownall, Rory Rapple, Martha Repp, Matt Richell, Miri Rubin, Garry Runciman, Ruth Runciman, Magnus Ryan, Ruth Scurr, Rebecca Small at LOccitane, Gareth Stedman Jones, Simon Szreter, Selfridges Food Hall, Marlena Spieler, Tate & Lyle, Sylvana Tomaselli, Robert Tombs, Georgie Widdrington, A. N. Wilson, Emily Wilson, Stephen Wilson.

I am also particularly grateful to the fellows of St Johns College Cambridge for their generosity in awarding me a research fellowship and for allowing me to use some of my time to write this book; also to the History Society of St Johns, to whom I presented some of the material in this book.

This book has been constructed in large part from secondary sources, and owes a special debt to the work of the scholars Bodog F. Beck, Eva Crane, Austin Fife, Juan Ramrez and Hilda Ransome. I have been grateful on several occasions to a delightful short work called Curiosities of Beekeeping by L. R. Croft.

Caroline Westmore has worked heroically to turn my text into a book. Special thanks must go to my editor, Caroline Knox, and to my literary agents, Sam Edenborough, Christy Fletcher, Pat Kavanagh and Emma Parry. This book would never have been written at all were it not for Pat, and might not have been finished were it not for Emma.

Tom and Natasha Runciman helped me to taste honey.

My greatest debt by far, in every possible way, is to David Runciman.

The author and publishers would like to acknowledge Faber and Faber Ltd for permission to quote from The Arrival of the Bee Box and The Bee Meeting from Collected Poems by Sylvia Plath. Extracts from Constance Garnetts translations of War and Peace (Heinemann, 1971) and Anna Karenina (Heinemann, 1972) by Leo Tolstoy are printed with the permission of A. P. Watt Ltd, on behalf of the Executor of the Estate of Constance Garnett. Lines from C. Day-Lewiss translation of Virgils Fourth Georgic are reprinted by permission of PFD on behalf of the Estate of C. Day-Lewis C. Day-Lewis 1940.

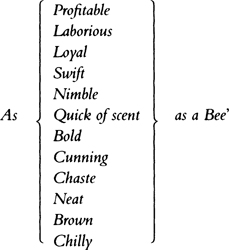

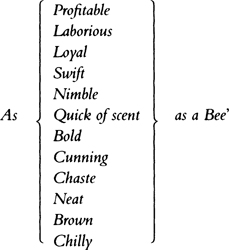

The Bee, therefore excelling in many qualities, it is fitly said in the proverb

Charles Butler, The Feminine Monarchy or the History of the Bees, 1609

Introduction

Thou seemst a little deity!

Anacreon, Ode 34, To the bee (fifth century BC )

I MAGINE A WORLD in which the lights went off until daybreak as soon as the sun went down; a world in which, year in and year out, you could never taste anything sweeter than a piece of fruit; a world in which there was no satisfactory way of getting drunk. Imagine huddling in the dark on a cold winters night with neither sweets nor alcohol for comfort. If you got wounded in this world, your wound might well fester, untreated. If you got a sore throat, there would be no syrup to soothe it. It would not be unlivable, this life, but it would not contain much of the sweetness that helps us to swallow the bitter pill of existence.

This is what life would have been like for our distant ancestors had it not been for the presence of honeybees, those marvellous insects the Apis mellifera, which supplied them, if they could afford it, with artificial light from wax, with intoxication from mead, and, above all, with energy from golden, dripping honey, a medicine as well as a food, whose sweetness in a culture without sugar must have seemed simply wondrous. If the bees had never made honey and wax, human civilization would still have survived just. If you chanced to live in the right part of the world, you might get some artificial light from oil, or from tallow candles, and sweetness from dates (the only things in nature sweeter than honey), and, eventually, alcohol from grain or grapes, and you could treat your wounds with various soothing leaves, which might or might not stop you from dying. But something would be missing. A little poetry would be missing. From the earliest times, bee colonies supplied humans not just with some of lifes luxuries, but also with food for the imagination. High on honey, our ancestors decided that bees despite their stings were the most mysterious and therefore magical creatures.

A classic medieval image of a wholly benevolent beehive, from the fourteenth-century Luttrell Psalter

Peering into the glowing hexagonal rows of the bees home, men thought they should look and learn. Here was not just something delicious to eat, but a little society in miniature. Here were architects, and here was a ruler. Were the bees, who worked so ceaselessly and produced such goodies, a kind of message from God (or Nature) to humankind? The ancients returned obsessively to the idea that the bees were the only creatures to rival men in their social gifts. The bee is wiser and more ingenious than all other animals, insisted one ancient authority, before adding that this insect almost reaches the intelligence of man.

This superhero bee on the label of Capilano Honey from Australia shows how the love of bees has endured

Others went further, and wondered if the bees didnt have some advantages which men lacked. Pliny the Elder, the Roman encyclopedist, felt that bees surpassed humans in various ways. He suggested, wishfully but understandably, that bees were the only insects to have been created for the benefit of men. The praise that Pliny heaped on the bees would be repeated countless times over the course of human history; it was already a bit of a clich by the time his book was completed, in AD 77. Among all insect species, he wrote, the pride of place is reserved for bees. Why? Because:

Bees collect honey: the sweetest, finest, most health-promoting liquid. They make wax and combs for a thousand purposes, put up with hard toil and construct building works. Bees have a government; they pursue individual schemes but have collective leaders. What is especially astonishing, they have manners more advanced than those of other animals, whether wild or tame. Nature is so great that from a tiny, ghost-like creature she has made something incomparable. What sinews or muscles can we compare with the enormous efficiency and industry shown by bees? What men, in heavens name, can we set alongside these insects which are superior to men when it comes to reasoning? For they recognize only what is in the common interest.