Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

To Rick Whitaker

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Forgetting Elena: A Novel

The Joy of Gay Sex (coauthored)

Nocturnes for the King of Naples: A Novel

States of Desire: Travels in Gay America

A Boys Own Story: A Novel

Caracole: A Novel

The Darker Proof: Stories from a Crisis

The Beautiful Room Is Empty

Genet: A Biography

The Burning Library: Essays

Our Paris: Sketches from Memory

Skinned Alive: Stories

The Farewell Symphony: A Novel

Marcel Proust: A Life

The Married Man: A Novel

The Fl neur: A Stroll Through the Paradoxes of Paris

Fanny: A Fiction

Arts and Letters: Essays

My Lives: A Memoir

Chaos: A Novella and Stories

Hotel de Dream: A New York Novel

Rimbaud: The Double Life of a Rebel

City Boy: My Life in New York During the 1960s and 70s

Sacred Monsters: New Essays on Literature and Art

Jack Holmes and His Friend: A Novel

Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris

Our Young Man: A Novel

Contents

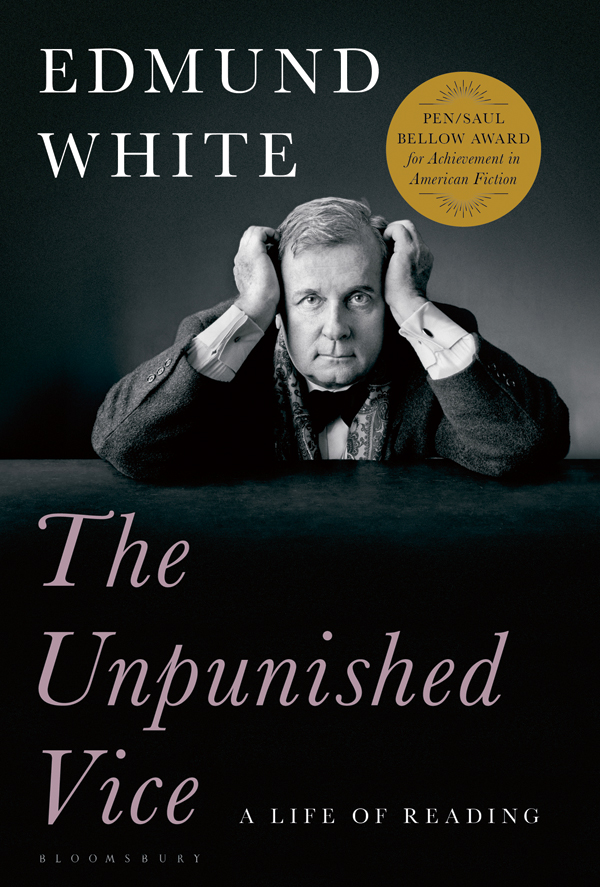

Reading is at once a lonely and an intensely sociable act. The writer becomes your ideal companioninteresting, worldly, compassionate, energeticbut only if you stick with him or her for a while, long enough to throw off the chill of isolation and to hear the intelligent voice murmuring in your ear. No wonder Victorian parents used to read out loud to the whole family (a chapter of Dickens a night by the precious light of the single candle); theres nothing lonely about laughing or crying togetheror shrinking back in horror. Even if solitary, the readers inner dialogue with the writerquestioning, concurring, wondering, objecting, pityingfills the empty room under the lamplight with silent discourse and the expression of emotion.

Who are the most companionable novelists? Marcel Proust and George Eliot; certainly theyre the most intelligent, able to see the widest implications of the simplest act, to play a straightforward theme on the mighty organs of their minds: soft/loud, quick/slow, complex/chaste, reedy/orchestral. But we also cherish Leo Tolstoys uncanny empathy for diverse people and even animals, F. Scott Fitzgeralds lyricism, Colettes worldly wisdom, James Merrills wit, Walt Whitmans biblical if agnostic inclusiveness, Annie Dillards sublime nature descriptions. When I was a youngster I loved novels about the Lost Dauphin or the Scarlet Pimpernel or the Three Musketeersadventure books enacted in the clear, shadowless light of Good and Evil.

If we are writers, we read to learn our craft. In college I can remember reading a now-forgotten writer, R. V. Cassill, whose stories showed me that a theme, once taken up, could be dropped for a few pages only to emerge later, that in this way one could weave together plot elements. That seems so obvious now, but I needed Cassill to teach me the secrets of polyphonic development. In her extremely brief notes on writing, Elizabeth Bowen taught me that you cant invent a body or faceyou must base your description on a real person. Bowen also revealed how epigrams can be buried into a flowing narrative. She said that in dialogue people are either deceiving themselves or striving to deceive others and that they rarely speak the disinterested, unvarnished truth. Henry Jamess The Turn of the Screw showed me how Chinese-box narrators can destabilize the reader sufficiently to make a ghost story seem plausible.

Sometimes I read now to fill up my mind-banks with new coinsnew words, new ideas, new turns of phrase. From Joyce Carol Oates I learned to alternate italicized passages of mad thought with sentences in Roman type narrating and describing in a straightforward manner. To me the first half of D. H. Lawrences The Rainbow shows how far prose can go toward the poetic without falling into a sea of rose syrup.

Each classic is eccentric. Samuel Beckett is both bleak and comic. Karl Ove Knausgaard is both boring and engrossing. Proust is so long-winded he often loses the thread of an anecdote; too many interpellations can make a story nonsensicaland sublimely interesting, if the narrator possesses a sovereign intellect. V. S. Naipauls The Enigma of Arrival is both confiding and absurdly discreet (he doesnt mention hes living in the country with his wife and children, for instance; nor does he tell us that his madman-proprietor is one of Englands most interesting oddballs, Stephen Tennant). I suppose all these examples demonstrated to me that any excess can be rewarding if it explores the writers unique sensibility and goes too far. The farthest reaches of fiction are marked by Mircea Crtrescus monumental Blinding and Samuel Delanys The Mad Man and Compass by Mathias nardand there are no books more memorable.

If I watch television, at the end of two hours I feel cheated and undernourished (although Im always being told of splendid new TV dramas I havent discovered yet); at the end of two hours of reading, my mind is racing and my spirit is renewed. If the book is good

I rely on other writers and experienced readers to guide me to the good books. Yiyun Li told me to read Rebecca Wests The Fountain Overflows . Ill always be grateful to her. My husband, the writer Michael Carroll, lent me Richard Yatess The Easter Parade and Joy Williamss stories in Honored Guest . The novelist and essayist Edward Hower, Alison Luries husband, gave me a copy of Elizabeth Taylors stories, reissued by the New York Review of Books (not that Elizabeth Taylor, silly). Because I lived in Paris sixteen years, I discovered many great French writers, including the contemporaries Jean Echenoz and Emmanuel Carrre and the extraordinary historical novelist Chantal Thomas, and I spoke at the memorial ceremony of the champion of the nouveau roman , Alain Robbe-Grillet, who was a friend. Julien Gracq is in my pantheon, along with the Irish writer John McGahern.

Ive read books in many capacitiesfor research, as a teacher, as a judge of literary contests, and as a reviewer.

As early as Nocturnes for the King of Naples (a title I stole from Haydn, who also contributed the title of my novel The Farewell Symphony ), I was researching the odd bit. In that book, I liked the Baroque confusion between sacred and sexual love, and I threaded into it references to several poets and mystics. I also disguised poems (couplets, a sonnet, a sestina); I wrote them out as prose. With my Caracole I drew inspiration from the life of Germaine de Stalbut also from eighteenth-century Venetian memoirs I consulted in the library of the Palazzo Barbaro, where I spent several summers. Perhaps my biggest research job was my biography of Jean Genet, though I was helped on a daily basis by the great Genet scholar Albert Dichy. We read copies of the lurid magazine Detective , which inspired Genet at several junctures; old copies were stored in the basement of Gallimard. I read the semi-gay Montmartre novels (such as J sus-la-Caille by Francis Carco) that Genet surpassed; we consulted everything we could find in print about the Black Panthers. I found a store on lower Broadway that sold political posters and other ephemera. Since it was the first major Genet biography, we interviewed hundreds of people hed known. And all this was before Google or the Internet. For my other two biographies (short ones on Proust and Arthur Rimbaud) I did no original research, though I had to read the enormous secondary literature on each writer; much of my work was done at the main Princeton library.