This book made available by the Internet Archive.

LOOK AT ME

N

Once a thing is known it can never be unknown. It can only be forgotten. And, in a way that bends time, so long as it is remembered, it will indicate the future. It is wiser, in every circumstance, to forget, to cultivate the art of forgetting. To remember is to face the enemy. The truth lies in remembering.

My name is Frances Hinton and I do not like to be called Fanny. I work in the reference library of a medical research institute dedicated to the study of problems of human behaviour. I am in charge of pictorial material, an archive, said to be unparalleled anywhere else in the world, of photographs of works of art and popular prints depicting doctors and patients through the ages. It is an encyclopaedia of illness and death, for in early days few maladies were curable and they seem therefore to have exerted a dreadful fascination over the minds of men. We are particularly interested in dreams and madness, and our collection is rather naturally weighted towards the incalculable or the undiagnosed. Problems of human behaviour still continue to baffle us, but at least in the Library we have them properly filed.

I work with Olivia, my friend, and we send off for

photographs to museums and galleries, and when they arrive we mount them on sheets of cardboard and type all the relevant information about them on a paper slip which is then fixed to the mount. It is extremely interesting, in a hopeless sort of way. So many lunatics, so many punitive hospitals, so much deterioration. And so much continuity, so much still unsolved. That, I am glad to say, is not my job, although it seems to exercise the minds of most of the people for whom I work.

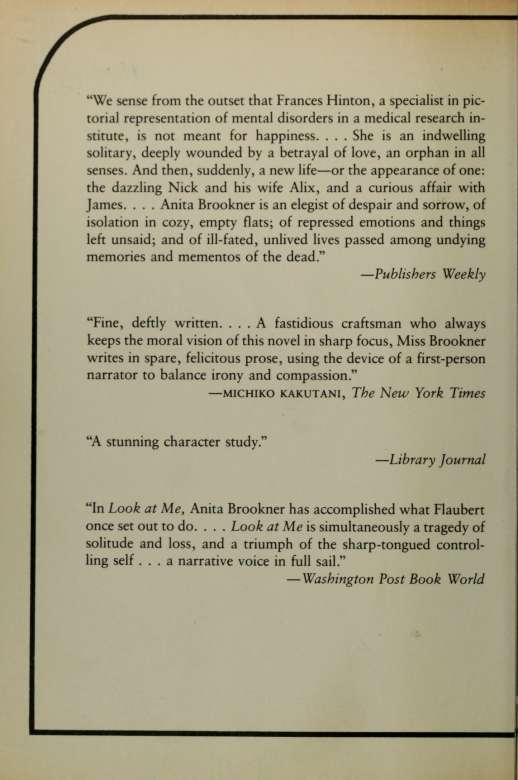

Take the problem of melancholy, for example. I could almost write a treatise on melancholy, simply from looking through the files. In old prints melancholy is usually portrayed as a woman, dishevelled, deranged, surrounded by broken pitchers, leaning casks, torn books. She may be sunk in unpeaceful sleep, heavy limbed, overpowered by her inability to take the world's measure, her compass and book laid aside. She is very frightening, but the person she frightens most is herself. She is her own disease. Diirer shows her wearing a large ungainly dress, winged, a garland in her tangled hair. She has a fierce frown and so great is her disarray that she is closed in by emblems of study, duty, and suffering: a bell, an hourglass, a pair of scales, a globe, a compass, a ladder, nails. Sometimes this woman is shown surrounded by encroaching weeds, a cobweb undisturbed above her head. Sometimes she gazes out of the window at a full moon, for she is moonstruck. And should melancholy strike a man it will be because he is suffering from romantic love: he will lean his padded satin arm on a velvet cushion and gaze skywards under the nodding plume of his hat, or he will grasp a thorn or a nettle and indicate that he does not sleep. These men seem to me to be striking a bit of a pose, unlike the women, whose melancholy is less picturesque. The women look as if they are in the grip of an affliction too serious to be put into words. The men, on the other

hand, appear to have dressed up for the occasion, and are anxious to put a noble face on their suffering. Which shows that nothing much has changed since the sixteenth century, at least in that respect.

Cures for melancholy include music and scourging. It is thought that some of the great religious figures of the past were melancholies. El Greco even chose models from the asylum of Toledo for his pictures of saints and apostles.

Next to melancholy in our filing system is madness, and this section too is heavily patronized. Here, the good news is that quite a bit has changed: madmen were once thought to be incredibly amusing, and there are far too many popular prints, most of them English, I am sorry to say, of funny men hitting themselves on the head or pulling faces at one another. But of course this material can be very serious indeed, particularly as quite a few artists have a close understanding of this sad condition. How powerful lunatics are! Once they were nude, struggling, chained. They tore their hair and hid their faces. A medieval emblem of a madman, on a Tarot card, shows a giant figure dressed in skins, a raven on his shoulder, playing the bagpipes. Only Gericault seems to have shown the mad as creatures of dignity, but of course he lived in the great age when the shackles of the insane were struck off, and in some cases the patients were allowed to wear their own clothes. And it is said that Gericault was mad himself, at least from time to time, and this would undoubtedly deepen his sense of kinship with this strange population. The world of obsession, of delusion, turns the eyes of Gericault's madmen red with suspicion, or opens them wide with un-corrupted innocence. Sometimes they think they are children, or generals, or kings. In a horrendous picture by Goya, a large vaulted room with a high window is filled with a melee of furious nude figures, some fighting,

some grovelling, some simply crawling on the ground, yet even among these barely human creatures some have adorned themselves with paper crowns or with feathers or with chains of office. Goya also shows a figure slipping away from the normal human condition, with an animal head and huge feet, his body electrified by a storm of black chalk strokes. I know very little about Goya's state of mind apart from the fact that it must have been unenviable. He seems to have been on the edge of the tolerable all his life.

We also have a full range of deaths, and here the fear is unending. Death too can be a woman, with a skull, misleadingly handsome. But death is usually a skeleton which one perceives to be male. Death can menace the mother with the child, can invade the comfortable dwelling of the merchant, can interrupt the miser counting his gold or the scholar in his study. Death can waylay the bridegroom and his bride; death can attend the wedding feast. Death, wearing a crown, his bony foot on a globe, holds a glass inscribed with the words, The mirror that flatters not. And death is unpeaceful, as I well know. At the end temptation comes in the form of gargoyles and devils, and a fight for the soul of the dying will be waged by angels around his bed of suffering.

The section most popular in our Library is the one devoted to dreams. There are dreams of women, dreams of God, dreams of whirlwinds, of giant birds, of dogs, of fame. St Helena dreams of the True Cross, which she was later to find. The most famous dream image of all shows a man with his head sunk on his folded arms and bats flying all around him. All these dreams seem terribly disturbing. I never dream myself, and I suppose I am very lucky. I am also fortunate enough to be in excellent health, and this fact, and the fact that I have no specialist knowledge, makes my work tolerable. If I were to be afflicted in any way, I doubt if I could look at

![Anita Anand - The Library Book. Anita Anand ... [Et Al.]](/uploads/posts/book/40194/thumbs/anita-anand-the-library-book-anita-anand-et.jpg)