ALSO BY RICHARD DAWKINS

The Selfish Gene

The Extended Phenotype

The Blind Watchmaker

River Out of Eden

Climbing Mount Improbable

Unweaving the Rainbow

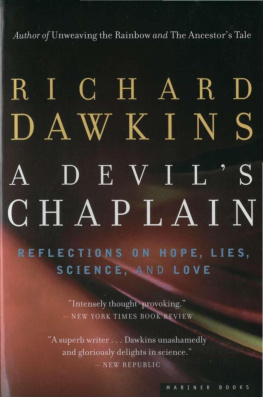

A Devils Chaplain

The Ancestors Tale

The God Delusion

The Greatest Show on Earth

The Magic of Reality (with Dave McKean)

An Appetite for Wonder

Brief Candle in the Dark

Science in the Soul

Outgrowing God

www.richarddawkins.net

Richard Dawkins

BOOKS DO FURNISH A LIFE

Reading and Writing Science

EDITED BY GILLIAN SOMERSCALES

TRANSWORLD

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Bantam Press

Copyright Richard Dawkins, 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover photographs Getty Images and Shutterstock

Cover design by R. Shailer/TW

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

ISBN: 978-1-473-57949-1

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

In memory of

Peter Medawar

Editors Introduction

Never has the communication of science been more important than it is today. If, as Francis Bacon literal and figurative Renaissance man believed, knowledge itself is power, then never have humans had more power to act in ways beneficial to the future of the planet, its very fabric and its myriad inhabitants and yet never, it seems, have they had less political will to make the necessary changes.

We live in a time when scientific knowledge and technological advance seem to be far outstripping the will to use them wisely. So a great burden falls on those with the knowledge that can inform human decision-making across the gamut of political, social, educational and commercial activity, and on those with the linguistic talent to command attention, to entice, to startle, above all to persuade. Those with both are the people who can, and who must, today speak truth to power if humanity is not to waste its potential in wasting the planet.

As I write this, humanity is hearing the loudest wake-up call that has rung out for many years, as the Covid-19 pandemic spreads across the world. Huge amounts of dedicated endeavour, political will, popular passion and rapid action have gone into efforts to combat this disease, its causes and its effects, all in a matter of months. One could forgive a cynic for noting the contrast with the laggardly response over decades to the long, slow burn of climate change which is still going on while we all try to save our own lives and livelihoods. On both fronts, we rely on science to show us ways to cope, ways to survive, ways to improve; and we rely on scientists not only to do their complex, painstaking, demanding work, but to tell the rest of us what they are doing, and how, and the likely effects of their discoveries.

Never, then, has the communication of science been more important; and never has there been more pressure on the communicators. We live amid a multiplicity of media outlets, a barrage of multiway argument, revelation and contestation, a plethora of on- and offline academic publishing streams, constant quick-fire exchanges on social (and all too often anti-social) media. Where in this cacophony are we to find patient argument alongside passionate partisanship, the excitement of discovery alongside the determined discipline of interrogation, all in the cause of reason and science, respect and responsibility for this Earth we inhabit?

Well, we can read Richard Dawkins, for a start. Fortunately for the rest of us, there are across the world a great number of determined individuals thinkers, researchers, speakers, writers dedicated to the work of both doing and communicating science. They work alone and in teams, standing on the shoulders of giants, joining hands with their coevals, reaching out to inform and draw in those outside their own circles. Richard Dawkins is one of the most eminent of them and, with characteristic energy and generosity of spirit, he is also one of the most active in promoting the efforts of others engaged in the same enterprise.

Hence this collection of short writings by an acknowledged master of the art of scientific communication. All are in one way or another connected with books, mostly science books the books that have furnished Richards life in science. The forewords, afterwords, introductions, reviews, essays reproduced here have all been composed to support, criticize or comment on work produced by others; to contribute to the vital task of spreading what we know through scientific method to be true, and defending it from those who would deny it, refuse it, misrepresent it.

In a volume all about communication, what better way to introduce each section than with a conversation? Each of the six parts of this collection begins with the edited transcript of a dialogue between Richard and another writer which reflects on its themes and relates them to the pressing issues of our time. And the collection as a whole is introduced by a new essay Richard has written specifically for this volume, in which he reflects upon The literature of science.

The work of scientific communication is never-ending. We should all be grateful to those who have dedicated their lives to it not only for the science they do, but for the words they write, both in and about the books with which we may furnish our own lives.

G.S.

Authors Introduction The Literature of Science

Literature:

a that kind of written composition valued on account of its qualities of form or emotional effect.

b The body of books and writings that treat of a particular subject.

(Shorter Oxford English Dictionary)

One of my teachers at Oxford encountered a junior colleague deep in the science branch of the Bodleian Library and stooped to murmur in the engrossed readers ear. Ah, dear boy, I see you are consulting the literature. Dont. It will only confuse you. Consulting and the give the game away. He was using literature in the special way scientists do, a version of the OEDs b definition above. The literature, for a scientist, is all those papers, often abstrusely and densely written, which pertain to a particular research topic. John Maynard Smith was once heard to say, There are those who read the literature. I prefer to write it. His witticism didnt do himself justice, for he was a generous scholar who scrupulously read and credited the work of other scientists. But his quip again serves to illustrate the two meanings of literature.