The Sick Man of Europe: The History of the Ottoman Empires Decline in the 19 th Century

By Charles River Editors

A picture of the Ottoman flag

About Charles River Editors

Charles River Editors is a boutique digital publishing company, specializing in bringing history back to life with educational and engaging books on a wide range of topics. Keep up to date with our new and free offerings with this 5 second sign up on our weekly mailing list , and visit Our Kindle Author Page to see other recently published Kindle titles.

We make these books for you and always want to know our readers opinions, so we encourage you to leave reviews and look forward to publishing new and exciting titles each week.

Introduction

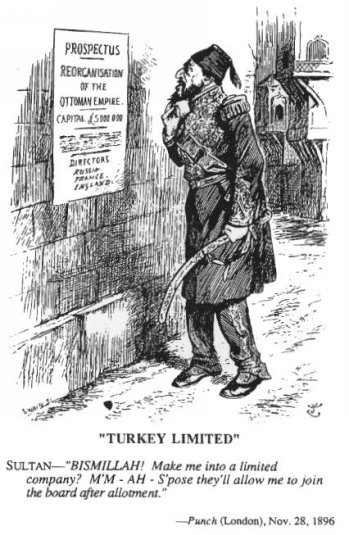

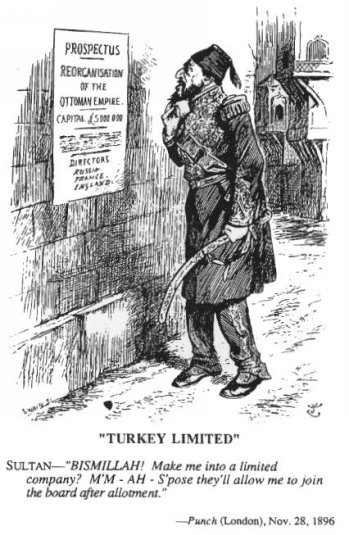

A 19 th century cartoon satirizing the decline of the Ottoman Empire

The Sick Man of Europe

In terms of geopolitics, perhaps the most seminal event of the Middle Ages was the successful Ottoman siege of Constantinople in 1453. The city had been an imperial capital as far back as the 4 th century, when Constantine the Great shifted the power center of the Roman Empire there, effectively establishing two almost equally powerful halves of antiquitys greatest empire. Constantinople would continue to serve as the capital of the Byzantine Empire even after the Western half of the Roman Empire collapsed in the late 5 th century. Naturally, the Ottoman Empire would also use Constantinople as the capital of its empire after their conquest effectively ended the Byzantine Empire, and thanks to its strategic location, it has been a trading center for years and remains one today under the Turkish name of Istanbul.

The end of the Byzantine Empire had a profound effect not only on the Middle East but Europe as well. Constantinople had played a crucial part in the Crusades, and the fall of the Byzantines meant that the Ottomans now shared a border with Europe. The Islamic empire was viewed as a threat by the predominantly Christian continent to their west, and it took little time for different European nations to start clashing with the powerful Turks. In fact, the Ottomans would clash with Russians, Austrians, Venetians, Polish, and more before collapsing as a result of World War I, when they were part of the Central powers.

The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople also played a decisive role in fostering the Renaissance in Western Europe. The Byzantine Empires influence had helped ensure that it was the custodian of various ancient texts, most notably from the ancient Greeks, and when Constantinople fell, Byzantine refugees flocked west to seek refuge in Europe. Those refugees brought books that helped spark an interest in antiquity that fueled the Italian Renaissance and essentially put an end to the Middle Ages altogether.

In the wake of taking Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire would spend the next few centuries expanding its size, power, and influence, bumping up against Eastern Europe and becoming one of the worlds most important geopolitical players. It was a rise that would not truly start to wane until the 19 th century.

The long agony of the sick man of Europe, an expression used by the Tsar of Russia to depict the falling Ottoman Empire, could almost blind people to its incredible power and history. Preserving its mixed heritage, coming from both its geographic position rising above the ashes of the Byzantine Empire and the tradition inherited from the Muslim Conquests, the Ottoman Empire lasted more than six centuries. Its soldiers fought, died, and conquered lands on three different continents, making it one of the few stable multi-ethnic empires in history, and likely one of the last. Thus, its somewhat inevitable that the history of its decline is at the heart of complex geopolitical disputes, as well as sectarian tensions that are still key to understanding the Middle East, North Africa and the Balkans.

When studying the fall of the Ottoman Empire, historians have argued over the breaking point that saw a leading global power slowly become a decadent empire. The failed Battle of Vienna in 1683 is certainly an important turning point for the expanding empire, as the defeat of Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha at the hands of a coalition led by the Austrian Habsburg dynasty, Holy Roman Empire and Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth marked the end of Ottoman expansionism. It was also the beginning of a slow decline during which the Ottoman Empire suffered multiple military defeats, found itself mired by corruption, and had to deal with the increasingly mutinous Janissaries (the Empires initial foot soldiers).

Despite it all, the Ottoman Empire would survive for over 200 more years, and in the last century of its life it strove to reform its military, administration and economy until it was finally dissolved. Years before the final collapse of the Empire, the Tanzimat (Reorganization), a period of swiping reforms, led to significant changes in the countrys military apparatus, among others, which certainly explains the initial success the Ottoman Empire was able to achieve against its rivals. Similarly, the drafting of a new Constitution ( Kann-u Ess , basic law ) in 1876, despite it being shot down by Sultan Abdul Hamid II just two years later, as well as its revival by the Young Turks movement in 1908, highlights the understanding among Ottoman elites that change was needed, and their belief that such change was possible.

Looking at the events of the empires last two centuries, and interpreting the fall of the Ottoman Empire as a slow but long decline is what could be called the accepted narrative. At the start of World War I, the Ottoman Empire was often described as a dwindling power, mired by administrative corruption, using inferior technology, and plagued by poor leadership. The general idea is that the Ottoman Empire was lagging behind, likely coming from the clear stagnation of the Empire between 1683 and 1826. Yet it can be argued that this portrayal is often misleading and fails to give a fuller picture of the state of the Ottoman Empire. The fact that the other existing multicultural Empire, namely the Austro-Hungarian Empire, also did not survive World War I should put into question this accepted narrative. Looking at the reforms, technological advances and modernization efforts made by the Ottoman elite between 1826 and the beginning of World War I, one could really wonder why such a thirst for change failed to save the Ottomans when similar measures taken by other nations, such as Japan during the Meiji era, did in fact result in the rise of a global power in the 20 th century.

During the period that preceded its collapse, the Ottoman Empire was at the heart of a growing rivalry between two of the competing global powers of the time, England and France. The two powers asserted their influence over a declining empire, the history of which is anchored in Europe as much as in Asia. However, while the two powers were instrumental in the final defeat and collapse of the Ottoman Empire, their stance toward what came to be known as the Eastern Question the fate of the Ottoman Empire is not one of clear enmity. Both England and France found, at times, reasons to extend the life of the sick man of Europe until it finally sided with their shared enemies. Russias stance toward the Ottoman Empire is much more clear-cut; the rising Asian and European powers saw the Ottomans as a rival, which they strove to contain, divide and finally destroy for more than 300 years in a series of wars against their old adversary.