George Orwell - Inside the Whale

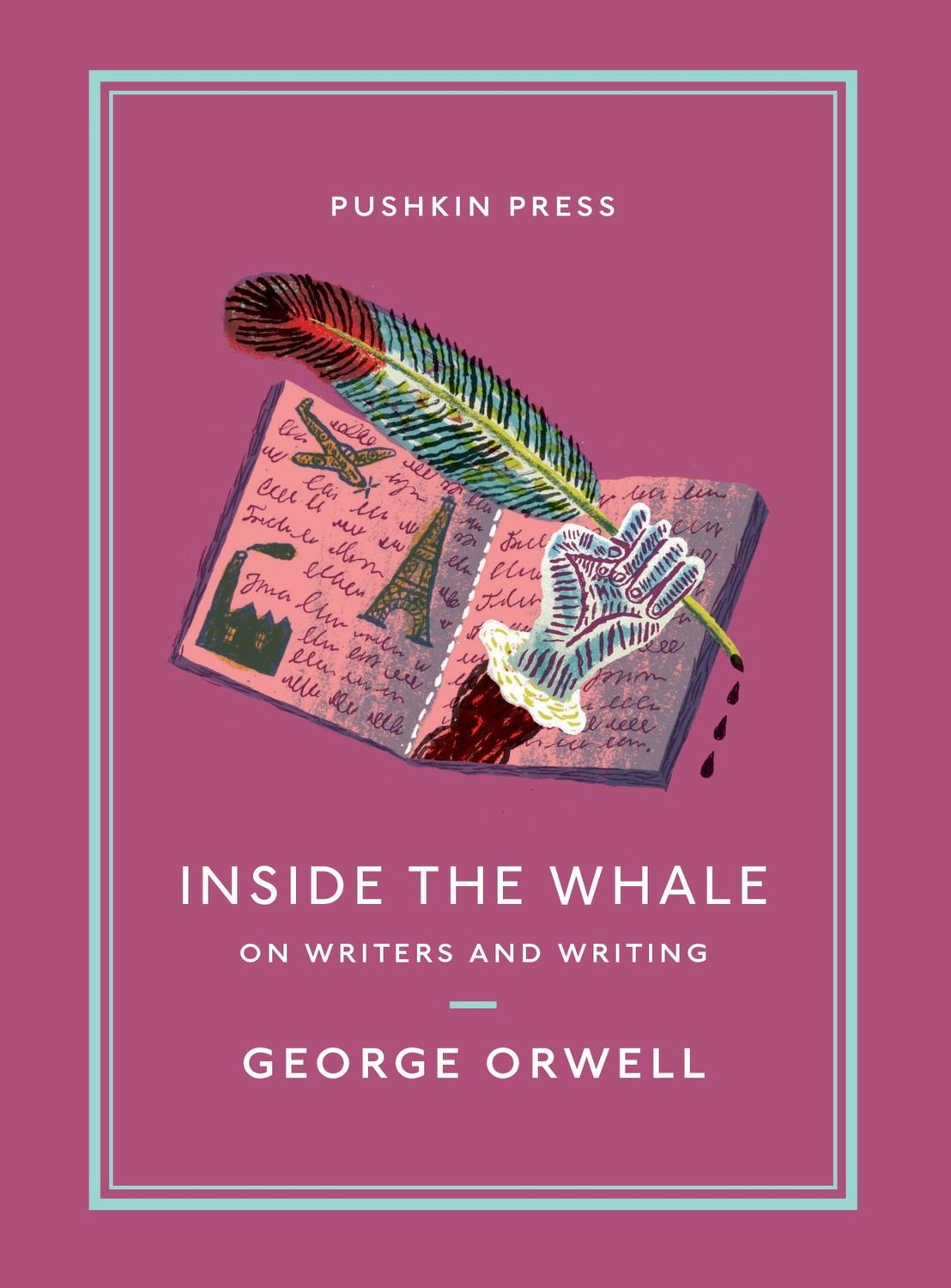

Here you can read online George Orwell - Inside the Whale full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Pushkin Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Inside the Whale

- Author:

- Publisher:Pushkin Press

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Inside the Whale: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Inside the Whale" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Inside the Whale — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Inside the Whale" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

W hen henry millers novel, Tropic of Cancer, appeared in 1935, it was greeted with rather cautious praise, obviously conditioned in some cases by a fear of seeming to enjoy pornography. Among the people who praised it were T. S. Eliot. Herbert Read, Aldous Huxley, John dos Passos, Ezra Pound on the whole, not the writers that are in fashion at this moment. And in fact the subject-matter of the book, and to a certain extent its mental atmosphere, belong to the twenties rather than to the thirties.

Tropic of Cancer is a novel in the first person, or autobiography in the form of a novel, whichever way you like to look at it. Miller himself insists that it is straight autobiography, but the tempo and method of telling the story are those of a novel. It is a story of the American Paris, but not along the usual lines, because the Americans who figure in it happen to be people without money. During the boom years, when dollars were plentiful and the exchange-value of the franc was low, Paris was invaded by such a swarm of artists, writers, students, dilettanti, sight-seers, debauchees and plain idlers as the world has probably never seen. In some quarters of the town the so-called artists must actually have outnumbered the working population indeed, it has been reckoned that in the late twenties there were as many as 30,000 painters in Paris, most of them impostors. The populace had grown so hardened to artists that gruff-voiced lesbians in corduroy breeches and young men in Grecian or medieval costume could walk the streets without attracting a glance, and along the Seine banks by Notre Dame it was almost impossible to pick ones way between the sketching-stools. It was the age of dark horses and neglected genii; the phrase on everybodys lips was Quand je serai lanc. As it turned out, nobody was lanc, the slump descended like another Ice Age, the cosmopolitan mob of artists vanished, and the huge Montparnasse cafs which only ten years ago were filled till the small hours by hordes of shrieking poseurs have turned into darkened tombs in which there are not even any ghosts. It is this world described in, among other novels, Wyndham Lewiss Tarr that Miller is writing about, but he is dealing only with the under side of it, the lumpenproletarian fringe which has been able to survive the slump because it is composed partly of genuine artists and partly of genuine scoundrels. The neglected genii, the paranoiacs who are always going to write the novel that will knock Proust into a cocked hat, are there, but they are only genii in the rather rare moments when they are not scouting about for the next meal. For the most part it is a story of bug-ridden rooms in working-mens hotels, of fights, drinking bouts, cheap brothels, Russian refugees, cadging, swindling and temporary jobs. And the whole atmosphere of the poor quarters of Paris as a foreigner sees them the cobbled alleys, the sour reek of refuse, the bistros with their greasy zinc counters and worn brick floors, the green waters of the Seine, the blue cloaks of the Republican Guard, the crumbling iron urinals, the peculiar sweetish smell of the Mtro stations, the cigarettes that come to pieces, the pigeons in the Luxembourg Gardens it is all there, or at any rate the feeling of it is there.

On the face of it no material could be less promising. When Tropic of Cancer was published the Italians were marching into Abyssinia and Hitlers concentration camps were already bulging. The intellectual foci of the world were Rome, Moscow and Berlin. It did not seem to be a moment at which a novel of outstanding value was likely to be written about American dead-beats cadging drinks in the Latin Quarter. Of course a novelist is not obliged to write directly about contemporary history, but a novelist who simply disregards the major public events of the moment is generally either a footler or a plain idiot. From a mere account of the subject-matter of Tropic of Cancer most people would probably assume it to be no more than a bit of naughty-naughty left over from the twenties. Actually, nearly everyone who read it saw at once that it was nothing of the kind, but a very remarkable book. How or why remarkable? That question is never easy to answer. It is better to begin by describing the impression that Tropic of Cancer has left on my own mind.

When I first opened Tropic of Cancer and saw that it was full of unprintable words, my immediate reaction was a refusal to be impressed. Most peoples would be the same, I believe. Nevertheless, after a lapse of time the atmosphere of the book, besides innumerable details, seemed to linger in my memory in a peculiar way. A year later Millers second book, Black Spring, was published. By this time Tropic of Cancer was much more vividly present in my mind than it had been when I first read it. My first feeling about Black Spring was that it showed a falling-off, and it is a fact that it has not the same unity as the other book. Yet after another year there were many passages in Black Spring that had also rooted themselves in my memory. Evidently these books are of the sort to leave a flavour behind them books that create a world of their own, as the saying goes. The books that do this are not necessarily good books, they may be good bad books like Raffles or the Sherlock Holmes stories, or perverse and morbid books like Wuthering Heights or The House with the Green Shutters. But now and again there appears a novel which opens up a new world not by revealing what is strange, but by revealing what is familiar. The truly remarkable thing about Ulysses, for instance, is the commonplaceness of its material. Of course there is much more in Ulysses than this, because Joyce is a kind of poet and also an elephantine pedant, but his real achievement has been to get the familiar on to paper. He dared for it is a matter of daring just as much as of technique to expose the imbecilities of the inner mind, and in doing so he discovered an America which was under everybodys nose. Here is a whole world of stuff which you have lived with since childhood, stuff which you supposed to be of its nature incommunicable, and somebody has managed to communicate it. The effect is to break down, at any rate momentarily, the solitude in which the human being lives. When you read certain passages in Ulysses you feel that Joyces mind and your mind are one, that he knows all about you though he has never heard your name, that there exists some world outside time and space in which you and he are together. And though he does not resemble Joyce in other ways, there is a touch of this quality in Henry Miller. Not everywhere, because his work is very uneven, and sometimes, especially in Black Spring, tends to slide away into mere verbiage or into the squashy universe of the Surrealists. But read him for five pages, ten pages, and you feel the peculiar relief that comes not so much from understanding as from being understood. He knows all about me, you feel; he wrote this specially for me. It is as though you could hear a voice speaking to you, a friendly American voice, with no humbug in it, no moral purpose, merely an implicit assumption that we are all alike. For the moment you have got away from the lies and simplifications, the stylized, marionette-like quality of ordinary fiction, even quite good fiction, and are dealing with recognizable experiences of human beings.

But what kind of experience? What kind of human beings? Miller is writing about the man in the street, and it is incidentally rather a pity that it should be a street full of brothels. That is the penalty of leaving your native land. It means transferring your roots into shallower soil. Exile is probably more damaging to a novelist than to a painter or even a poet, because its effect is to take him out of contact with working life and narrow down his range to the street, the caf, the church, the brothel and the studio. On the whole, in Millers books you are reading about people living the expatriate life, people drinking, talking, meditating and fornicating, not about people working, marrying and bringing up children; a pity, because he would have described the one set of activities as well as the other. In

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Inside the Whale»

Look at similar books to Inside the Whale. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Inside the Whale and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.