Table of Contents

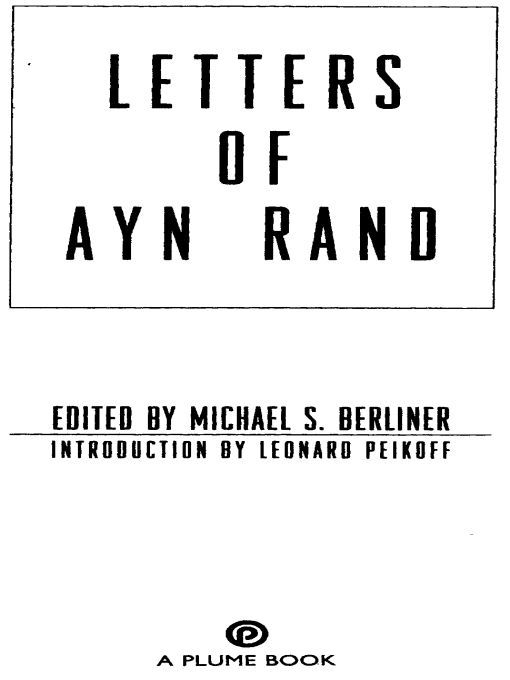

People always ask me: What was she [Ayn Rand] really like? My standard answer is: Read her novels; she was everything their creator would have to be. But now I have a follow-up answer: Read her letters.

from the Introduction by Leonard Peikoff

A remarkable volume that easily rises to the level of literature ... and, in the bargain, surprisingly ample self-revelation.

New York Times

Like everything she wrote, the letters are structured, lucid, original, and meticulously composed ... also warm, colorful, dramatic, and intense.

Detroit Free Press

Delightful and entertaining ... as readable as it is enlightening: a still-living legacy from one of the last of the great letter writers.

Tulsa World

Engagingly hale and generous.

The New Yorker

Adds greatly to our understanding of a most exceptional woman.... Her fiercely held beliefs fairly blaze off the page.

Booklist

A portrait of a heroine who forged and lived by her philosophy of Objectivism.

The Intellectual Activist

MICHAEL S. BERLINER has been executive director of the Ayn Rand Institute, a nonprofit educational organization devoted to the advancement in high schools and universities of the philosophy of Objectivism, since 1985. For fifteen years before that, he taught at California State University, Northridge, where he served as chairman of the Department of Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education. He received his B.A. in political science from the University of Michigan and Ph.D. in philosophy from Boston University.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following individuals and copyright holders have generously given permission to print material from previously unpublished correspondence: Christopher Cerf, the Estate of Cecil B. DeMille, Sen. Barry Goldwater, John Hospers, the Estate of Rose Wilder Lane, Ira Levin, Elizabeth T. Ogden, the Estate of Isabel Paterson, Robert Stack, and the Estate of Barbara Stanwyck.

The quoted letters of Frank Lloyd Wright are Copyright 1994 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and are used with the permission of the Foundation. All rights reserved.

Excerpts from the letters of H. L. Mencken are quoted by permission of the Enoch Pratt Free Library in accordance with the terms of the will of H. L. Mencken.

INTRODUCTION

I was a student and friend of Ayn Rands for thirty-one years, from 1951 when she was 46 and writing Atlas Shruggeduntil her death in 1982, at the age of 77. So people always ask me: What was she really like?

My standard answer is: Read her novels; she was everything their creator would have to be. But now I have a follow-up answer: Read her letters.

When Michael Berliner handed me the manuscript of this book a month ago, I did not know much about the letters, and I proceeded to read them through. I started out coolly, as an editor, but I was soon hooked; I became emotionally involved and even rapt. I ended in tears.

It is almost eerie to hear her inimitable voice again, so many years after her death, but this book is Ayn Rand, exactly as I knew her. It captures her mindand also her feelings, her actions, her achievements, her character, her soul. An authorized biography of Ayn Rand will appear in due course. But these letters will remain unique. Through them you can see her thinking and choosing and judging and reacting day by day, across decades, in virtually every aspect of her professional and personal life.

These letters do not merely tell you about Ayn Rands life. In effect, they let you watch her live it, as though you were an invisible presence who could follow her around and even read her mind.

The person you will meet in this book has several essential attributes.

The first thing you will see is that Ayn Rand does not merely agree or disagree with the ideas of her fans or associates; if she undertakes to answer someone, she methodically explains her conclusions; she offers a patientand often brilliantsentence-by-sentence analysis. She does not merely accept or reject a practical proposal; she works to identify its merits and drawbacks, then weighs them dispassionately. If a friend in trouble solicits her advice, she does not give a glib answer; she identifies the basic problem, often down to its philosophical roots, so that the individual can see for himself how to decide.

Ayn Rand not only says or doesshe says why; she always gives her reasons. Like the person I knew, therefore, her letters are the opposite of casual or purposeless. They are focused, deliberate, and bracingly logical. In a word, they display in lifelong practice the quality extolled as the top virtue by her own philosophy of Objectivism: rationality.

As a result of her method of thinking, Ayn Rand knew exactly what ideas and values she endorsed in every field and why. Hence her individualism and her integrityher refusal to sell out to any establishment, to contradict her own conclusions, or to compromise her work. I am not brave enough to be a coward, she once said. I see the consequences too clearly. In this respect, she was not like her hero, Howard Roark; on the contrary, he was like her, as these letters make clear. In 1934, for instance, when she was an impoverished beginner, an editor at an important publishing house suggested that she rewrite her first novel (We the Living) with the help of a collaborator. She replied, in part: If anyone is capable of improving that bookhe should have written it himself. I would prefer not only never seeing it in print, but also burning every manuscript of itrather than having William Shakespeare himself add one line to it which was not mine, or cross out one comma. Was she, then, a prima donna? Here are her next two sentences: I repeat, I welcome and appreciate all suggestions of changes to improve the book without destroying its theme, and I am quite willing to make them. But these changes will be made by me.

Because Ayn Rands value judgments, like her ideas, were products of her mind, they, too, were absolutes to her. Hence her unique intensity as a personmade of her unbreached commitment to her values, her pride in them, and her consequent complete openness about her feelings. She saw no more reason to repress her emotions than her convictions.

When Ayn Rand liked or disliked something, her friends knew it, as you will know it when, through these magically eloquent letters, you all but reexperience her passions: her enchantment with America; her bitter disappointment over the countrys slow deterioration (which, virtually alone, she saw in the 30s); the joy and agony of her creative work; her fierce battle against every obstacle, including poverty; her pleasure in her growing success, first as a screenwriter, then as a novelist; her childlike delight at an unexpected gift from a friend; her unforgiving anger at injustice or betrayal; her desperate kisses on paper to her parents and sisters trapped in Russia; her lifelong love for her husband, Frank OConnor; and the fundamental element conditioning all these emotions: her capacity to make moral judgments, that is, to condemn the evil and, above all, to revere the good, specifically, the greatness possible to man. As to this last: In 1934, she wrote a letter to thank an actor she did not know, whose performance onstage gave me, for a few hours, a spark of what man could be, but isnt.... The word