Table of Contents

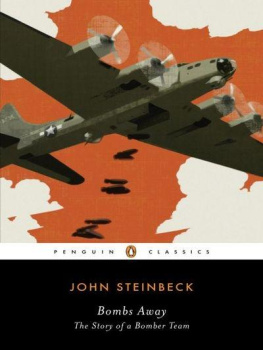

BOMBS AWAY

Born in Salinas, California, in 1902, JOHN STEINBECK grew up in a fertile agricultural valley about twenty-five miles from the Pacific coastand both valley and coast would serve as settings for some of his best fiction. In 1919 he went to Stanford University, where he intermittently enrolled in literature and writing classes until he left in 1925 without taking a degree. During the next five years, he supported himself as a laborer and journalist in New York City and then as a caretaker for a Lake Tahoe estate, all the time working on his first novel, Cup of Gold (1929). After marriage and a move to Pacific Grove, California, he published two California fictions, The Pastures of Heaven (1932) and To a God Unknown (1933), and worked on short stories later collected in The Long Valley (1938). Popular success and financial security came only with Tortilla Flat (1935), stories about Montereys paisanos. A ceaseless experimenter throughout his career, Steinbeck changed courses regularly. Three powerful novels of the late 1930s focused on the California laboring class: In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), and the book considered by many his finest, The Grapes of Wrath (1939). Early in the 1940s, Steinbeck became a filmmaker with The Forgotten Village (1941) and a serious student of marine biology with Sea of Cortez (1941). He devoted his services to the war, writing Bombs Away (1942) and the controversial play-novelette The Moon Is Down (1942). Cannery Row (1945), The Wayward Bus (1947), The Pearl (1947), A Russian Journal (1948), the experimental drama Burning Bright (1950), and The Log from the Sea of Cortez (1951) preceded publication of the monumental East of Eden (1952), an ambitious saga of the Salinas Valley and his familys history. The last decades of his life were spent in New York City and Sag Harbor with his third wife, Elaine, with whom he traveled widely. Later books included Sweet Thursday (1954), The Short Reign of Pippin IV: A Fabrication (1957), Once There Was a War (1958), The Winter of Our Discontent (1961), Travels with Charley in Search of America (1962), America and Americans (1966), and the posthumously published Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters (1969), Viva Zapata! (1975), The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights (1976), and Working Days: The Journals of The Grapes of Wrath (1989). He died in 1968, having won a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962.

JAMES H. MEREDITH is a former lieutenant colonel and professor of English at the United States Air Force Academy. He has served on several literary-society boards and has written about F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Stephen Crane, and Joseph Heller, as well as about Theodore Roosevelt, the American Civil War, and World War II. He is the author of Understanding the Literature of World War II (Greenwood Press, 1999) and Understanding the Literature of World War I (Greenwood Press, 2004), and is the co-editor of a forthcoming collection of essays, War in Hemingways Time (Kent State University Press, 2010). Currently, Professor Meredith is president of the Ernest Hemingway Foundation and Society and teaches American literature for Troy Universitys Global Campus.

Introduction

Ernest Hemingway once said he would rather have cut three fingers off his throwing hand than to have written such a book as Bombs Away (Baker 371). Besides the books obvious propagandistic qualities, what possibly bothered him more than anything else about Bombs Away was the fact that rather than emphasizing the emergence of an individual, as Hemingway would have done, Steinbeck instead focused on the development of a team or group. Steinbeck, who was at the time much more socially oriented than Hemingway, had been throughout his career emphasizing the united effort of Americans to overcome the economic and concomitant social woes of the 1930s Great Depression. At the same time, Hemingway wrote and published To Have and Have Not (1937), a novel about how one man attempts not only to overcome the economic downturn but to triumph over the New Deal bureaucratic functionaries as well. Now, with the advent of Americas involvement in another massive social problem, the global conflict against fascism, Steinbeck was willing to do his part in the war effort by writing a book about how the U.S. Army Air Forces recruited and developed a bomber team, a story that seemingly appealed to his literary sensibility. By the mid-1930s, fascism and military dictatorships had taken control over the governments of Italy, Japan, Germany, and Spain, and by September 1939 they had thrown the world into the most destructive war in history. America, of course, would join the fray after Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Steinbeck began writing this book in 1942.

In general, war was not necessarily Steinbecks literary terrain, whereas it most assuredly was Hemingways. Hemingway, in all of his writings about war, whether fiction or nonfiction, always emphasized individualistic heroism and the personal alienation and despair from mechanized modern warfare and the new technological instruments of terror. His was the stuff of modernism. On the other hand, Steinbecks literary sensibility in such works as Cannery Row, The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men, and East of Eden seemed to prefer group or composite portraits of diverse characters, which seemed to perfectly coincide with the Army Air Forces strategy of bringing together men from across a broad cross section of America and training them to work together for a common purpose as a bomber team.

John Steinbeck was a rather complicated man and writer. How else could one reconcile the fact that he would, in the middle of his career, write what can only be described as a propaganda piece for the United States government? Calling it propaganda, however, should not diminish Bombs Away in any way or suggest that the book is not an important work; it most assuredly is, especially as a significant artifact of a pivotal time in U.S. history. This book is successful primarily because it would indeed do, whether or not many Americans ever read the book, what it proposes to do, and that is make some Americans feel at ease about sending their sons to war in a modern flying machine; because it would provide a coherent glimpse at how the U.S. military was training for modern war; and because it put a uniquely American face on what would turn out to be one of the most destructive military strategic campaigns in history.

Purposefully written in the vernacular, to appeal to mothers and fathers throughout the country, Bombs Away, in the tradition of Walt Whitman during the American Civil War, is a contribution to American literature because it cogently conveys, in almost mythopoeic simplicity, the vital democratic regeneration of the United States in the face of a real and grave danger. Steinbeck writes, It is the intention of this book to set down in simple terms the nature and mission of a bomber crew and the technique and training of each member of it. This is where Steinbeck truly verges on the propagandistic: For the bomber crew will have a great part in defending this country and in attacking its enemies. It is the greatest team in the world. Propaganda, as defined by