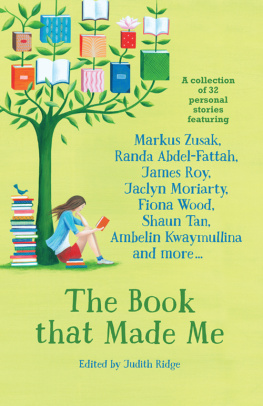

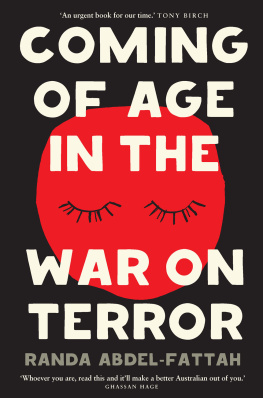

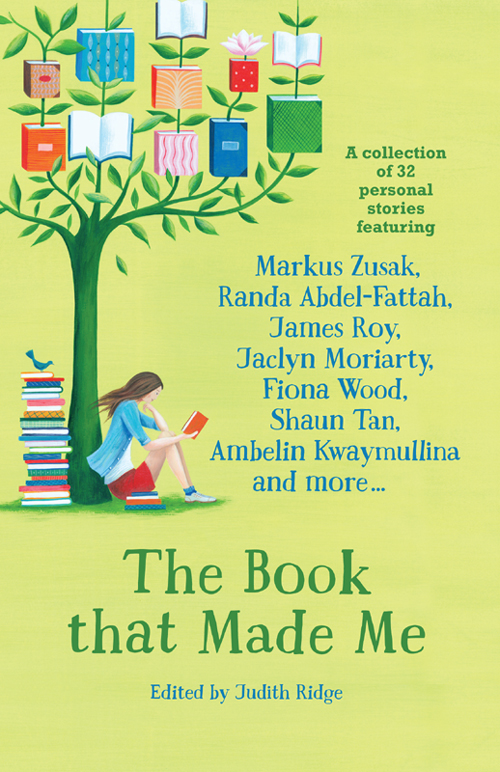

The Book That Made Me is a celebration of the books that influenced some of the most acclaimed authors from Australia and the world. Edited by Judith Ridge, it features non-fiction stories from 32 inspiring and award-winning authors including Markus Zusak, Jaclyn Moriarty, Shaun Tan, Mal Peet, Ambelin Kwaymullina, Simon French, Alison Croggon, Fiona Wood, Bernard Beckett, Ursula Dubosarsky, Rachael Craw, Sue Lawson, Benjamin Law, Cath Crowley, Kate Constable, James Roy, Will Kostakis, Randa Abdel-Fattah and many more. Royalties from the sale of the book will go to the Indigenous Literacy Foundation (ILF).

Foreword

Growing up, reading was my first and best thing. I dont remember not being able to read I was one of those precocious children who was reading before school, reading novels (Enid Blytons Adventures ofthe Wishing-Chair, to be precise) by the time I was in Year Two. For some people, reading is difficult for me, it was like osmosis. I just seemed to absorb it into my way of being in the world as soon as was humanly, and cognitively, possible. Any time my family couldnt find me skiving off from the washing up, or just disappeared for hours they knew that wherever theyd find me, in the loo or up a tree, Id have a book with me.

For me it was almost always fiction (when it wasnt Archie comics and Pink magazine an English girls magazine that published comic strips and pre-teen-suitable romance stories side by side with profiles of such top 70s pop stars as the Bay City Rollers, Paper Lace and The Rubettes. Google them and thank me later). I probably read five or six books a week as a kid, often re-reading old favourites multiple times, while falling for new delights borrowed from the school or local library. (Thanks, Auburn Council in Sydneys west you had the best collection an obsessive reader could have asked for.)

Later in life, though, Ive come to equally enjoy memoir stories of peoples lives. Not autobiography, strictly speaking, but slices of lives, and especially when they are the memoirs of writers. Writers memoirs, at their best, provide not merely insights into their childhoods, or romances, or whatever significant moments in their lives they choose to focus on, but often, indeed, almost always, they are meditations on creativity, and the role books and reading have played in the memoirists life. Memoirs such as Jeanette Wintersons Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal ? go so far as to suggest that books, and reading, can not only make a life, they can save it.

This growing fascination with writers reading lives led me to the creation of this book. I didnt know much about writers when I was a young reader. Apart from a few big names like Enid Blyton, or Ethel Turner, who wrote my beloved Seven Little Australians and whose grandchildren holidayed at the same beach we did, authors were simply names on books. Now, of course, writers are celebrities, and their readers often have opportunities to meet them. But still, I wondered, how great would it be for todays young readers to catch a glimpse into the books that helped build the writers they love? Thinking about the writers I knew and loved, I wondered, what was the book that made them the book that made them fall in love, or made them understand something for the first time? Made them think. Made them laugh. Made them angry. Made them feel safe. Made them feel challenged in ways they never knew they could be, emotionally, intellectually, politically. Made them readers, made them writers made them the person they are today? And so I asked them. The book you hold in your hands is the result.

As youll see when you start dipping into the essays, poems, memoir and other pieces in this collection, theres a fascinating variety of stories told by people who ended up making words and stories their living (and perhaps their life). Some of the books that made them were encountered when they were very small children see Ursula Dubosarskys charming verse account of her kindergarten readers. Some were primary-school aged (as with my own story, recounted below, and James Roys tribute to the Australian classic childrens novel Josh). Most, though, were in their teens and ready, as Emily Maguire so perfectly says in her essay about Frank Moorhouses novel Grand Days, for something to smash and explode their mind and their world wide open.

Some of the books youll read about were in fact comics; some were magazines (stolen, as in Benjamin Laws hilariously cheeky account, from an older sister). Some werent in paper form at all, but were stories passed down through family and culture Ambelin Kwaymullina for one reminds us of the source of all story, from the oral traditions of our ancestors, wherever we, or they, came from.

Whatever their form, and whatever the age the reader was when they were read, they were all books, stories, experiences that one way or another changed the reader. For good.

For myself, the book that made me the kind of reader I am and, I suspect, played no small part in my decision to make a life trying to get inside books and figure out how they work, was the first book I ever read that challenged me on an intellectual and, for want of a better word, creative level.

The book was The Flame Takers, a novel by the Australian author Lilith Norman. It was published in 1973, and I would have read it that year or a year or two, at most, later. I knew Normans work well Id been reading her for years in the New South Wales TheSchool Magazine, where she worked on the editorial staff. Id also read all of her previous novels, all more or less in the realist mode, about recognisably real children in recognisably real places and situations. Her best-known book at the time was probably Climb a Lonely Hill, about children stranded in the desert after a car accident. (Surviving the Australian environment was a favourite theme of childrens writers of the 1960s and 70s.)

The Flame Takers, though, was something else.

The protagonists are still very real young teenage brother and sister Mark and Joanna Malory, in their early years of high school at Sydney Boys and Girls High respectively (Norman was a proud alumna of Sydney Girls High School). The narrative begins as Marks story hes a gifted musician, the son of theatrical parents and grandparents, all of whose creative talents slowly start being drained away by some unknown, mysterious force. Audaciously, about a third of the way into the novel, Norman switches our attention from Mark to Joanna, the blessedly (so Joanna herself says) untalented member of the family, who is the one left to find the cause of her familys flames their creativity being lost.

The Flame Takers was the first book I found difficult, whose meaning was slippery and opaque, whose language and story spiralled around me like elusive, elliptical phantoms. It was the first book I remember where the story didnt immediately present itself to me, but where I had to enter into the book in all its strangeness and make my own sense, make my own meaning. It was the book that introduced me to the intense pleasures of entering deep within the very bones of a story and working out its secrets from the inside out.

And while I may have ended up here anyway, I cant help but think it was