George Orwell

19031950

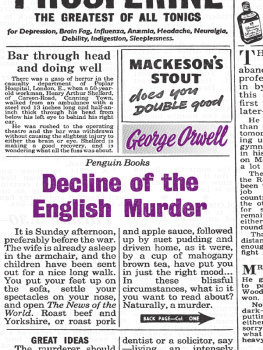

George Orwell

Decline of the English Murder

PENGUIN BOOKS GREAT IDEAS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

Clink written August 1932

Decline of the English Murder first published in Tribune, 15 February 1946

Just Junk But Who Could Resist It? first published as the Saturday Essay, Evening Standard, 5 January 1946

Good Bad Books first published in Tribune, 2 November 1945

Boys Weeklies first published in Horizon, March 1940

Womens Twopenny Papers extract from As I Please first published in Tribune, 28 July 1944

The Art of Donald McGill first published in Horizon, September 1941

Hop-Picking Diary, written 25 August to 8 October 1931

This selection first published in Penguin Books 2009

Copyright the Estate of Sonia Brownell Orwell, 1984

All rights reserved

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-195655-8

Contents

Clink

This trip was a failure, as the object of it was to get into prison, and I did not, in fact, get more than forty-eight hours in custody; however, I am recording it, as the procedure in the police court etc. was fairly interesting. I am writing this eight months after it happened, so am not certain of any dates, but it all happened a week or ten days before Xmas 1931.

I started out on Saturday afternoon with four or five shillings, and went out to the Mile End Road, because my plan was to get drunk and incapable, and I thought they would be less lenient towards drunkards in the East End. I bought some tobacco and a Yank Mag against my forthcoming imprisonment, and then, as soon as the pubs opened, went and had four or five pints, topping up with a quarter bottle of whisky, which left me with twopence in hand. By the time the whisky was low in the bottle I was tolerably drunk more drunk than I had intended, for it happened that I had eaten nothing all day, and the alcohol acted quickly on my empty stomach. It was all I could do to stand upright, though my brain was quite clear with me, when I am drunk, my brain remains clear long after my legs and speech have gone. I began staggering along the pavement in a westward direction, and for a long time did not meet any policemen, though the streets were crowded and all the people pointed and laughed at me. Finally I saw two policemen coming. I pulled the whisky bottle out of my pocket and, in their sight, drank what was left, which nearly knocked me out, so that I clutched a lamp-post and fell down. The two policemen ran towards me, turned me over and took the bottle out of my hand.

THEY : Ere, what you bin drinking? (For a moment they may have thought it was a case of suicide.)

I : Thass my boll whisky. You lea me alone.

THEY : Coo, es fair bin bathing in it! What you bin doing of, eh?

I : Bin in boozer avin bit o fun. Christmas, aint it?

THEY : No, not by a week it aint. You got mixed up in the dates, you ave. You better come along with us. Well look after yer.

I : Why shd I come along you?

THEY : Jest sos well look after you and make you comfortable. Youll get run over, rolling about like that.

I : Look. Boozer over there. Less go in ave drink.

THEY : Youve ad enough for one night, ole chap. You best come with us.

I : Where you takin me?

THEY : Jest somewhere as youll get a nice quiet kip with a clean sheet and two blankets and all.

I : Shall I get drink there?

THEY : Course you will. Got a boozer on the premises, we ave.

All this while they were leading me gently along the pavement. They had my arms in the grip (I forget what it is called) by which you can break a mans arm with one twist, but they were as gentle with me as though I had been a child. I was internally quite sober, and it amused me very much to see the cunning way in which they persuaded me along, never once disclosing the fact that we were making for the police station. This is, I suppose, the usual procedure with drunks.

When we got to the station (it was Bethnal Green, but I did not learn this till Monday) they dumped me in a chair & began emptying my pockets while the sergeant questioned me. I pretended, however, to be too drunk to give sensible answers, & he told them in disgust to take me off to the cells, which they did. The cell was about the same size as a Casual Ward cell (about 10 ft. by 5 ft. by 10 ft. high), but much cleaner & better appointed. It was made of white porcelain bricks, and was furnished with a W. C., a hot water pipe, a plank bed, a horsehair pillow and two blankets. There was a tiny barred window high up near the roof, and an electric bulb behind a guard of thick glass was kept burning all night. The door was steel, with the usual spy-hole and aperture for serving food through. The constables in searching me had taken away my money, matches, razor, and also my scarf this, I learned afterwards, because prisoners have been known to hang themselves on their scarves.

There is very little to say about the next day and night, which were unutterably boring. I was horribly sick, sicker than I have ever been from a bout of drunkenness, no doubt from having an empty stomach. During Sunday I was given two meals of bread and marg. and tea (spike quality), and one of meat and potatoes this, I believe, owing to the kindness of the sergeants wife, for I think only bread and marg, is provided for prisoners in the lock-up. I was not allowed to shave, and there was only a little cold water to wash in. When the charge sheet was filled up I told the story I always tell, viz. that my name was Edward Burton, and my parents kept a cake-shop in Blythburgh, where I had been employed as a clerk in a drapers shop; that I had had the sack for drunkenness, and my parents, finally getting sick of my drunken habits, had turned me adrift. I added that I had been working as an outside porter at Billingsgate, and having unexpectedly knocked up six shillings on Saturday, had gone on the razzle. The police were quite kind, and read me lectures on drunkenness, with the usual stuff about seeing that I still had some good in me etc. etc. They offered to let me out on bail on my own recognizance, but I had no money and nowhere to go, so I elected to stay in custody. It was very dull, but I had my Yank Mag, and could get a smoke if I asked the constable on duty in the passage for a light prisoners are not allowed matches, of course.

Next page