Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

We hope you enjoyed reading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

ALSO AVAILABLE BY BERND HEINRICH

Bumblebee Economics

One Mans Owl

A Year in the Maine Woods

The Trees in My Forest

Mind of the Raven

Why We Run

Winter World

The Snoring Bird

Summer World

The Nesting Season

Life Everlasting

The Homing Instinct

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bernd Heinrich is Professor Emeritus of Biology at the University of Vermont and is the author of numerous books, including Bumblebee Economics, Why We Run, Mind of the Raven, and most recently, The Homing Instinct. His work has been featured in Scientific American, Discover, and The New York Times, among other places. He has received the John Burroughs Medal for nature writing and has been nominated for a National Book Award for Science. He lives in Vermont.

Simon & Schuster Paperbacks

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

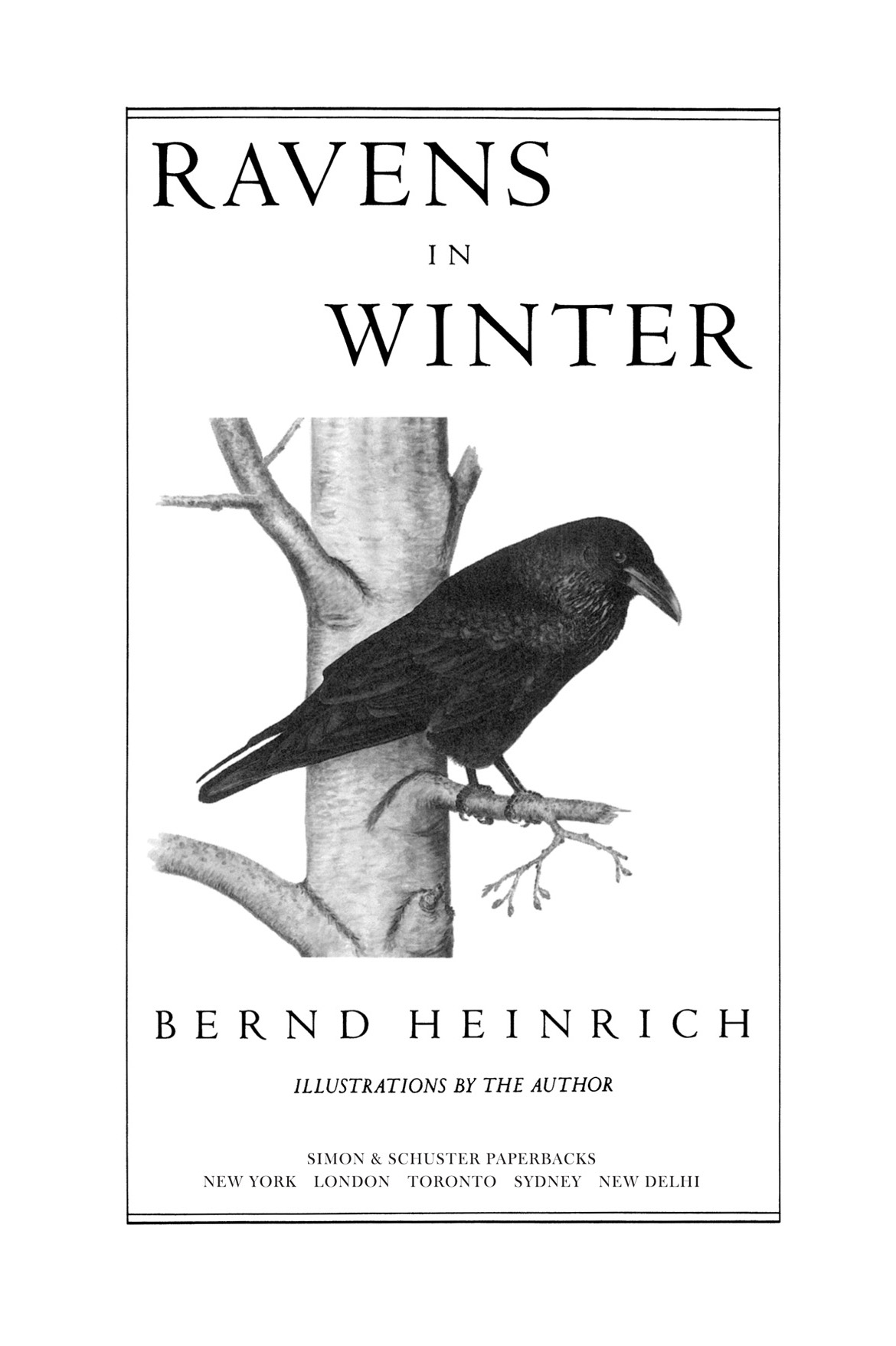

Copyright 1989 by Bernd Heinrich

Introduction copyright 2014 by Bernd Heinrich

Originally published in 1989 by Summit Books.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Paperbacks Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster trade paperback edition October 2014

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Cover illustration by Bernd Heinrich

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-1-4767-9456-3 (pbk)

ISBN 978-1-4767-9457-0 (ebook)

T O ALL THE RAVEN MAINIACS

WHO ANSWERED THE CALL

CONTENTS

NOTE ON THE NEW EDITION

Ravens in Winter is now celebrating its twenty-fifth anniversary. It is a scientific detective story derived from a commonplace sighting I made on October 18, 1984, in the Maine woods. I had observed the puzzling behavior of a large group of ravens that I thought might have been sharing a prized food bonanzaa moose carcass. But such sharing made absolutely no sense to me. It went against the grain of everything I had learned in my pursuit of classical biology. I was then officially an insect biologist with fourteen years of studying the physiology and behavior of bumblebees just recently behind me. Biology, the study of life, is all about finding generalities behind often seemingly idiosyncratic differences: when I saw those otherwise highly aggressive and territorial birds all sharing the same food bonanza, I could not help but think they held some profound and interesting secret, maybe even one that could apply to humans.

I had always been interested in birds, but felt we knew them well. Yet my observation that day seemed totally at odds with everything I knew. There were several possibilities, but there had to be one answer and that answer would reveal something new and wonderful about ravens and perhaps about animals in general. The question was so important that it would need to be solved and I wanted to leave a record of how it was solved. I thought, however, that the journey might be even more interesting than the destination. It would definitely be difficult because in the Maine woods ravens were not only uncommon but absurdly alert and shy of humans. I felt that the process of solving a scientific puzzle, using techniques that were available to almost everyonebecause I had no special resources myselfwould make for interesting reading and show how science is done or can be done by anyone venturing to tread on new ground. My task was to sort out and reject various hypotheses by experimentation and observation, as is the process of science.

The challenges were quite daunting, but the prize lured me on, and not always in the right direction. The false starts were ultimately essential, because each one narrowed the possibilities, leading me, hopefully, in the right direction. Not knowing anything about ravens proved to be a blessing because I was not biased by previous knowledge but informed by it. My writing was directly done from my research in the field and because I was typing-illiterate I did not use a computer. Yet when I submitted a draft of my notes for the book to the late Anne Freedgood, my editor at Summit Books, she was excited and worked on it over the weekend, handing it back to me all marked up in pencil. I thank her still for her encouragement and guidance.

Little did I suspect what a Pandoras box my book would open. In the thirty years since its publication there has been an explosion of research on ravens and other birds of the crow family, and the findings are nothing if not astounding. I feel a new window has been opened into the minds of animals, one never before suspected.

I was highly honored when the publisher agreed to reprint Ravens in Winter after its long hibernation in obscurity overshadowed by more recent knowledge-based books, including my own Mind of the Raven . Although the latter became a winner of the John Burroughs Medal for natural history writing, to me the more simple Ravens in Winter is by far the more important book, because it represents the passions, joys, and sometimes heartache of what seemed to me at the time a life poured wholeheartedly into an endeavor equivalent to Sir Edmund Hillary tackling Mount Everest for the first time. I had not done anything like it before, or since.

When considering the reissue of this book, the question came up of what to include: whether more, or less, of anything. I thought of perhaps deleting the appendix, which includes my hard-won data. I felt that this data in charts and graphs might have been off-putting to many readers because it gave a technical flavor to the book, which is not its thrust. But I decided to keep it in, to preserve the original.

When I originally wrote the book, I needed to include the appendix to justify the conclusion and the story, but the story has now not only been justified but greatly expanded. I also considered writing a new appendix, to include what had been done since. However, I decided against that because so much has been accomplished in the years after the books initial publication, by so many dedicated and professionally competent scientists, that anything I might try to synthesize would be deficient. This, then, is the story of a beginning, and it gives a flavor of the Maine woods in winter, the ravens in the wild, and the people whose passions united in solving a gripping scientific riddle.

PREFACE

A S AN ACADEMIC field biologist, I have the duty of finding out about our natural world. I also get privileges, like a sabbatical leave. Most of my colleagues in North America tend to spend their sabbatical years in distant, exotic lands to get to know new organisms or to see new perspectives on old biological puzzles. I went instead to my retreat in Maine because I had seen ravens there behaving in what seemed to me an irrational way, and I wanted to find out why.

Next page