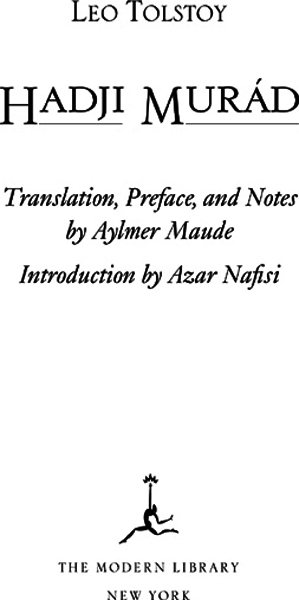

Leo Tolstoy - Hadji Murad

Here you can read online Leo Tolstoy - Hadji Murad full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Random House Publishing Group, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Hadji Murad

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hadji Murad: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Hadji Murad" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Hadji Murad — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Hadji Murad" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Count Lev (Leo) Nikolayevich Tolstoy was born on August 28, 1828, at Yasnaya Polyana (Bright Glade), his familys estate located 130 miles southwest of Moscow. He was the fourth of five children born to Count Nikolay Ilyich Tolstoy and Marya Nikolayevna Tolstoya (ne Princess Volkonskaya, who died when Tolstoy was barely two). He enjoyed a privileged childhood typical of his elevated social class (his patrician family was older and prouder than the tsars). Early on, the boy showed a gift for languages as well as a fondness for literatureincluding fairy tales, the poems of Pushkin, and the Bible, especially the Old Testament story of Joseph. Orphaned at the age of nine by the death of his father, Tolstoy and his brothers and sister were first cared for by a devoutly religious aunt. When she died in 1841 the family went to live with their fathers only surviving sister in the provincial city of Kazan. Tolstoy was educated by French and German tutors until he enrolled at Kazan University in 1844. There he studied law and Oriental languages and developed a keen interest in moral philosophy and the writings of Rousseau. A notably unsuccessful student who led a dissolute life, Tolstoy abandoned his studies in 1847 without earning a degree and returned to Yasnaya Polyana to claim the property (along with 350 serfs and their families) that was his birthright.

After several aimless years of debauchery and gambling in Moscow and St. Petersburg, Tolstoy journeyed to the Caucasus in 1851 to join his older brother Nikolay, an army lieutenant participating in the Caucasian campaign. The following year Tolstoy officially enlisted in the military, and in 1854 he became a commissioned officer in the artillery, serving first on the Danube and later in the Crimean War. Although his sexual escapades and profligate gambling during this period shocked even his fellow soldiers, it was while in the army that Tolstoy began his literary apprenticeship. Greatly influenced by the works of Charles Dickens, Tolstoy wrote Childhood, his first novel. Published pseudonymously in September 1852 in the Contemporary, a St. Petersburg journal, the book received highly favorable reviewsearning the praise of Turgenevand overnight established Tolstoy as a major writer. Over the next years he contributed several novels and short stories (about military life) to the Contemporaryincluding Boyhood (1854), three Sevastopol stories (18551856), Two Hussars (1856), and Youth (1857).

In 1856 Tolstoy left the army and went to live in St. Petersburg, where he was much in demand in fashionable salons. He quickly discovered, however, that he disliked the life of a literary celebrity (he often quarreled with fellow writers, especially Turgenev) and soon departed on his first trip to western Europe. Upon returning to Russia, he produced the story Three Deaths and a short novel, Family Happiness, both published in 1859. Afterward, Tolstoy decided to abandon literature in favor of more useful pursuits. He retired to Yasnaya Polyana to manage his estate and established a school there for the education of children of his serfs. In 1860 he again traveled abroad in order to observe European (especially German) educational systems; he later published Yasnaya Polyana, a journal expounding his theories on pedagogy. The following year he was appointed an arbiter of the peace to settle disputes between newly emancipated serfs and their former masters. But in July 1862 the police raided the school at Yasnaya Polyana for evidence of subversive activity. The search elicited an indignant protest from Tolstoy directly to Alexander II, who officially exonerated him.

That same summer, at the age of thirty-four, Tolstoy fell in love with eighteen-year-old Sofya Andreyevna Bers, who was living with her parents on a nearby estate. (As a girl she had reverently memorized whole passages of Childhood.) The two were married on September 23, 1862, in a church inside the Kremlin walls. The early years of the marriage were largely joyful (thirteen children were born of the union) and coincided with the period of Tolstoys great novels. In 1863 he not only published The Cossacks, but began work on War and Peace, his great epic novel that came out in 1869.

Then, on March 18, 1873, inspired by the opening of a fragmentary tale by Pushkin, Tolstoy started writing Anna Karenina. Originally titled Two Marriages, the book underwent multiple revisions and was serialized to great popular and critical acclaim between 1875 and 1877.

It was during the torment of writing Anna Karenina that Tolstoy experienced the spiritual crisis that recast the rest of his life. Haunted by the inevitability of death, he underwent a conversion to the ideals of human life and conduct that he found in the teachings of Christ. A Confession (1882), which was banned in Russia, marked this change in his life and works. Afterward, he became an extreme rationalist and moralist, and in a series of pamphlets published during his remaining years Tolstoy rejected both church and state, denounced private ownership of property, and advocated celibacy, even in marriage. In 1897 he even went so far as to renounce his own novels, as well as many other classics, including Shakespeares Hamlet and Beethovens Ninth Symphony, for being morally irresponsible, elitist, and corrupting. His teachings earned him numerous followers in Russia (We have two tsars, Nicholas II and Leo Tolstoy, a journalist wrote) and abroad (most notably, Mahatma Gandhi) but also many opponents, and in 1902 he was excommunicated by the Russian holy synod. Prompted by Turgenevs deathbed entreaty (My friend, return to literature!), Tolstoy did produce several more short stories and novelsincluding the ongoing series Stories for the People, The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), The Kreutzer Sonata (1889), Master and Man (1895), Resurrection (1899), and Hadji Murd (published posthumously)as well as a play, The Power of Darkness (1886).

Tolstoys controversial views produced a great strain on his marriage, and his relationship with his wife deteriorated. Until the day I die she will be a stone around my neck, he wrote. I must learn not to drown with this stone around my neck. Finally, on the morning of October 28, 1910, Tolstoy fled by railroad from Yasnaya Polyana headed for a monastery in search of peace and solitude. However, illness forced Tolstoy off the train at Astapovo; he was given refuge in the stationmasters house and died there on November 7. His body was buried two days later in a forest at Yasnaya Polyana.

Dont despair of becoming perfect.

Leo Tolstoy, from a letter to Valeria Arsenyeva.

I have done nothing but copy out Hadji Murd, Countess Tolstoy wrote in her journal in 1909, a year before her husbands death; its so good I simply could not tear myself away from it. Sonya Tolstoy was an astute judge of her husbands work and a devoted admirer, claiming to have copied out War and Peace nine times. Yet many prominent writers and thinkers have surpassed her in their enthusiastic praise of Hadji Murd. Isaac Babel and the philosopher Ludvig Wittgenstein have been among its ardent admirers, and one critic, Harold Bloom, has gone so far as to claim that Hadji Murd is my personal touchstone, for the sublime of prose fiction, to me the best story in the world, or at least the best that I have ever read.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Hadji Murad»

Look at similar books to Hadji Murad. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Hadji Murad and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.