THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

The letters of Willa Cather copyright 2013 by The Willa Cather Literary Trust

Introduction, annotation, commentary, and compilation copyright 2013 by Andrew Jewell and Janis Stout

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

eBook ISBN: 978-0-307-95931-7

Harcover ISBN: 978-0-307-959300-0

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cather, Willa, 18751947.

The selected letters of Willa Cather / edited by Andrew Jewell and Janis Stout.1st ed.

p. cm.

This is a Borzoi book.

ISBN 978-0-307-95930-0 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-307-95931-7 (ebook)

1. Cather, Willa, 18731947Correspondence.

2. Novelists, American20th centuryCorrespondence.

I. Jewell, Andrew (Andrew W.)

II. Stout, Janis P. III. Title.

PS 3505. A 87 Z 48 2013 813.52dc23

[B] 2012036882

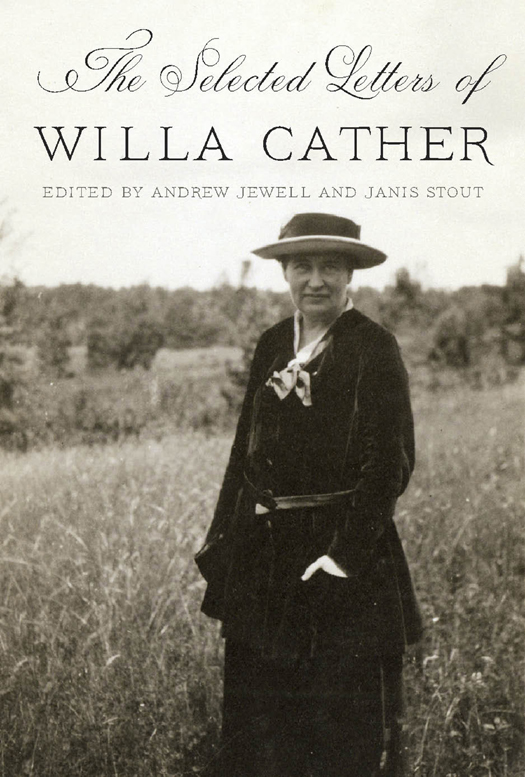

Cover photograph: Willa Cather in Jaffrey, New Hampshire, 1920s, probably taken by Edith Lewis. Archives and Special Collections, University of NebraskaLincoln Libraries.

Cover design by Megan Wilson

Manufactured in the United States of America

v3.1

Contents

Introduction

B EFORE W ILLA C ATHER DIED , she did what she could to prevent this book from ever existing. She made a will that clearly forbade all publication of her letters, in full or in part. And now we flagrantly defy Cathers will in the belief that her decision, made in the last, dark years of her life and honored for more than half a century, is outweighed by the value of making these letters available to readers all over the world.

Why did she put such restrictions in her will? Various answers have been proposed. Some believe that Cather was guarding her privacy, perhaps worried that the letters she dashed off over the years, not thinking of herself as a public figure, would compromise her literary reputation. Some have wondered if she sought to conceal a secret buried in her years of correspondence, some sign of an indiscretion or uncontrolled passion. Many people, following James Woodresss characterization of her in Willa Cather: A Literary Life, are convinced that Cather was obsessed with her privacy and that the willtogether with her supposed systematic collecting and burning of letterswas simply an expression of a personality seeking to control all access to itself. Many have believed she actually did burn all her letters, or almost all, and the will was a kind of backstop.

Our research on Willa Cathers letters calls into question all of these assumptions about Cather, her character, and her motivations. Except for an isolated incident or two, there is no evidence that she systematically collected and destroyed her correspondence. This claim is overwhelmingly demonstrated by the large volume of surviving documents: about three thousand Cather letters are now known to exist, and new caches continue to appear. If Cather or appear to be isolated incidents rather than part of a larger pattern of obliteration.

Nevertheless, Cathers testamentary restriction on the publication of her letters was clearly driven by a desire to restrict the readership of them. We do not believe that desire emerged from a need to shield herself or protect a secret, but instead was an act consistent with her long-held desire to shape her own public identity. In her maturity, Cather was a skillful self-marketer, and a major element of her marketing strategy was to limit her publicly available texts to those she had meticulously prepared. She did not fill shelves with hastily written novels or fleeting topical essays, but toiled over each book until it succeeded to the best of her ability. Sometimes she delayed the publication of a novel by months or even years in order to achieve her artistic goals. She even contributed to the design of the physical books, considering each element that might communicate something of her work to the reader. She specified her margin preferences for My ntonia, had ideas about the font type for Death Comes for the Archbishop, and thwarted most efforts to create paperback editions during her lifetime. Her strategy was extremely successful. By positioning herself not as a popular writer but as a literary artist, she was able to give herself the space to be such an artist while also financially succeeding in the marketplace. Her lovely, quiet, episodic novel about seventeenth-century Quebec, Shadows on the Rock, was one of the top-selling books of 1931. It was not a success because readers were rushing to read a novel about colonial Canada, but because the novel was written by the celebrated author Willa Cather.

We can guess that Cather may have believed that an edition of her letters In this way, the resistance to the publication of her letters was consistent with her resistance, in her later years, to lecturing, interviews, and other forms of exposing her self to the public.

Cathers suppression of the publication of her letters may indeed have helped cement her reputation as a true artist, and today that reputation is virtually unchallenged. In the nearly seven decades since her death, her works have continued to be read, studied, and celebrated, and both general readers and contemporary writers as diverse as A. S. Byatt and David Mamet celebrate her fine artistry and her absolute dedication to her craft. And rightly so: many of Cathers novels and stories are among the finest writings of the twentieth century, rich and complex in their meaning-making, yet elegant and pristine on their surfaces. She manages both to enchant readers with her prose and to move them with her insights into human experience.

We fully realize that in producing this book of selected letters we are defying Willa Cathers stated preference that her letters remain hidden from the public eye. But even her will itself envisions a moment when her preferences would not rule the day; acknowledging her inability to govern publication decisions indefinitely from beyond the grave, it leaves the decision for publication to the sole and uncontrolled discretion of my Executors and Trustee.

The concerns that we believe motivated her to assert her preference are no longer valid. Cathers reputation is now as secure as artistic reputations can ever be, and her works will continue to speak for themselves. These lively, illuminating letters will do nothing to damage her reputation. Instead, we can see from our twenty-first-century perspective that her letters heighten our sense of her complex personality, provide insights into her methods and artistic choices as she worked, and reveal Cather herself to be a complicated, funny, brilliant, flinty, sensitive, sometimes confounding human being. Such an identity is far more satisfyingand more honestthan that of a pure artist, unmoved by commercial motivations, who devoted herself strictly to her creations and nothing else.