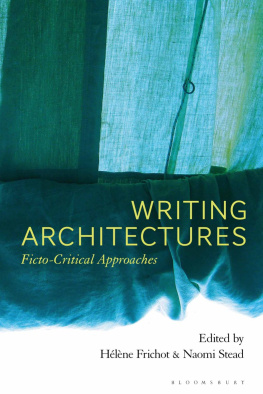

Experimental Fiction

Also Available from Bloomsbury

The Creative Screenwriter: Exercises to Expand Your Craft , Dr Craig Batty and Zara Waldeback

The Post-War British Literature Handbook , Katharine Cockin

The Modernism Handbook , Philip Tew

Bending Genre: Essays on Creative Nonfiction , Margot Singer

Maverick Screenwriting: A Manual for the Adventurous Screenwriter , Josh Golding

Experimental Fiction

An Introduction for Readers

an d W riters

Julie Armstrong

For my Creative Writing students, past and present, at MMU Cheshire

Preface and Contents

Who the book is intended for and why

This book is for writers and readers of fiction, especially those who are studying, or have an interest in, experimental literary works. The aim is to enrich readers knowledge, understanding and appreciation of such works and to enable writers to heighten their powers of imagination whilst developing their craft.

The history of experimental writing, from modernism to the Beats, to postmodernism and beyond, will be traced. In addition, Experimental Fiction will analyse why the twenty-first century is a time ripe for change for the reader and the writer.

How the book is organized

Experimental Fiction: An Introduction for Readers and Writers has an Introduction, four sections Modernism, Beats, Postmodernism, A Ne w Era Dawning and a Conclusion.

The introduction will pose, and hope to find answers to, the following questions:

Alongside the historical discussion of each movement, at the end of each chapter there are creative writing exercises designed to stimulate writing experimentation and to introduce techniques which will help learning in terms of the practice of creative writing. References for further reading are also listed. Each section has an introduction.

Followed by chapters:

Followed by chapters:

Followed by chapters:

Followed by chapters:

The conclusion will pose, and hope to find answers to, the following questions:

Having read Experimental Fiction: An Introduction for Readers and Writers and completed the exercises, readers and writers will be better informed and more skilful creative writing practitioners.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following colleagues who have kindly supported me in the writing of this book: Ms Carola Boehm, Mr John Deeney, Mr Terry Fox, Dr Robert Graham, Professor Dick Hartley, Ms Angi Holden, Dr Meriel Lland, Professor Berthold Schoene, Ms J o Selley, Ms Bev Steven, Professor Michael Symmons Roberts and D r Ja ne Turner. Many thanks are also due to the team at Bloomsbury: Mark Richardson, Avinash Singh and, in particular, editor David Avital for his vision and rigorous reading of the manuscript.

I would like to thank my Creative Writing students, especially Context 1, 2 and Historical Perspectives students; this book is for you.

The word experimental is a contested and historically contingent term when applied to fiction. Many readers, writers and critics are unsure about giving fiction the label experimental , and as a consequence, there are many questions that need to be fully considered before the label can be applied to literary works. For example, if a writer is creating work in accordance with new not pre-established conventions of writing, can this fiction be classified as experimental? How can the actual experiment in a piece of unconventional writing be defined? Does fiction which expresses the writers restlessness with form and content be characterized as experimental? Does what was once labelled experimental in one historical period become mainstream fiction in another? Is experimental simply a label which identifies the next trend in fiction? Is fiction deemed experimental at the time of writing, or is it established as such by later generations?

Any new writing will owe something to the past and also something to the future in the shaping of ideologies and styles. However, it can be said, the novel is often a product of its time and place. Although, experimental literary works become comprehensible after their unfamiliar structures, forms and content have been conventionalized over time.

It can be acknowledged that there are writers throughout history whose intention is to experiment and create fiction that sets out to break new ground and deviate from traditional realist fiction. Virginia Woolf, for example, declared in her diary that she sought to experiment with her craft and, as a result, she discovered a new form for a new novel. Jack Kerouac also set out to experiment with his writing and to produce work that contested mainstream, middle-class America. He felt that his writing could not be fully realized through existing traditional novel conventions; they would simply not allow him to tell the story he wanted to tell. By creating his own rules or essentials , as he referred to them, Kerouac did not produce novels but a new prose-narrative form. He used technical devices of epic poetry, which, together with his spontaneous prose, revitalized his writing and resulted in the poetic sprawl On the Road .

And yet, it can also be noted that there are other writers who produce new works by simply expressing their own, often idiosyncratic personalities, in response to the internal and external worlds they inhabit. There are also writers who are creating works in order to make sense of the world and their place in it, and in so doing, they produce works which depart from tradition realist fiction, a form considered to be too restricting to express some writers thoughts and ideas. As a consequence, they create new forms, styles and genres of literary work. In addition, there are writers who consciously react against traditional realist fiction with the intention of creating work which will bring about self-realization and change in peoples lives, and in so doing, they too establish new forms and content. All of the above writers will be explored in this book.

The concerns of individual writers are not always explicit. However, some writers have written essays or diaries or given interviews voicing their preoccupations and citing what their intentions are when creating fiction that opposes traditional realist fiction. Jack Kerouac, for example, stated in numerous interviews that he was preoccupied with writing that had feeling as opposed to craft. He favoured a spontaneous, improvised style, like jazz, a style that was fast, mad, confessional and suited the bohemian content of his work. Gertrude Stein conducted experiments to access the subconscious in order to research into the process of automatic writing. Later, she converted the data into new literary fiction. Other contemporary writers, such as the late Scottish- born author Iain Banks, created fiction considered to be thought experiments. In such works, fiction is a vehicle for a writer to investigate ideas and concepts for example, the Culture series of fiction, which centres around the Culture, a semi-anarchist utopia, consisting of humanoid races managed by advanced artificial intelligence. The main themes of the novels, such as The Player of Games and The State of the Art , are the dilemmas that an idealistic hyper-power faces in dealing with civilizations that do not share its ideals and behaviour.

Jeanette Winterson has written about her desire to create fiction that addresses twenty-first-century needs. Indeed, many experimental writers, for example, William Gibson and Jon McGregor, despite being different, are both seeking to create new forms, techniques, content and styles to enable them to express what they want to express through their writing. They are looking for new ways to tell the new stories that they wish to tell. More traditional forms, styles and techniques are too restricting, simply not suited to the ideas and content they wish to explore.

Next page