William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2016

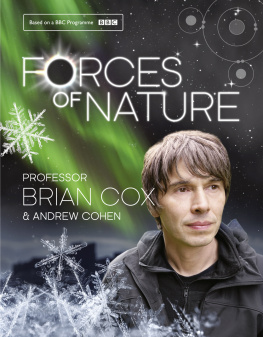

Text Brian Cox and Andrew Cohen 2016

Photographs individual copyright holders

Diagrams, design and layout HarperCollins Publishers 2016

The BBC logo is a trademark of the British Broadcasting Corporation and is used under licence.

BBC logo BBC 2014

The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

Cover photographs BBC 2016 (Brian Cox); other images Shutterstock.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780007488827

Ebook Edition June 2016 ISBN: 9780007488834

Version: 2016-06-27

For my dad, David.

Brian Cox

For Benjamin, Martha, Theo, Dan, Jake, Lyla, Ellie, Toby, Phoebe, Max, Zak, Josh, Isaac and Tabitha because curious young minds always ask the smartest of questions.

Andrew Cohen

Contents

Chapter 1

SYMMETRY

Chapter 2

MOTION

Chapter 3

ELEMENTS

Chapter 4

COLOUR

SEARCHING FOR THE DEEPEST ANSWERS TO THE SIMPLEST QUESTIONS

What beauty. I saw clouds and their light shadows on the distant dear Earth.... The water looked like darkish, slightly gleaming spots.... When I watched the horizon, I saw the abrupt, contrasting transition from the Earths light-coloured surface to the absolutely black sky. I enjoyed the rich colour spectrum of the Earth. It is surrounded by a light blue aureole that gradually darkens, becoming turquoise, dark blue, violet, and finally coal black.

Yuri Gagarin

On 5 May 1961, Alan Shepards Freedom 7 launched into space from Cape Canaveral, Florida, for NASAs first ever suborbital flight.

Taking a different perspective

The first day or so we all pointed to our countries. The third or fourth day we were pointing to our continents. By the fifth day we were aware of only one Earth.

Sultan bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud, Space Shuttle STS-51-G

T his is a book about science. What is science? Thats a good question, and there may be as many answers as there are scientists. I would say that science is an attempt to understand the natural world. The explanations we discover can often seem abstract and separate from the familiar, but this is a false impression. Science is about explaining the everyday minutiae of human experience. Why is the sky blue? Why are stars and planets round? Why does the world keep on turning? Why are plants green? These are questions a child might ask, but they are certainly not childish; they generate a chain of answers that ultimately lead to the edge of our understanding.

If you dig deep enough, most questions end with uncertainty. The sky is blue because of the way light interacts with matter, and the way light interacts with matter is determined by symmetries that constrain the laws of nature. Well encounter these concepts later in the book. But if one keeps on digging, and asks why those particular symmetries, or why there are laws of nature at all, then we are into the glorious hazy place in which scientists live and work; the space between the known and the unknown. This is the domain of the research scientist, and it is a place of curiosity and wonder.

Grander questions lurk in the half-light. How did life on Earth begin? Is there life on other worlds? What happened in the first few moments after the Big Bang? These are questions that have a sense of depth and a feeling of complexity and intractability, but the techniques and processes by which we look for answers are no different to those deployed in discovering why the sky is blue. This is an important point. If a question sounds deep, it doesnt mean that the way to answer it is to retire to the wilderness for a year, sit cross-legged and hope for something to occur to you. Rather, the answers are often constructed on foundations generated by the systematic and careful exploration of simpler questions. This idea is central to our book. In seeking to understand the everyday world the colours, structure, behaviour and history of our home we develop the knowledge and techniques necessary to step beyond the everyday and approach the Universe beyond.

Planet Earth is the easiest place in the Universe to study because we live on it, but it is also confusingly complicated. For one thing, its the only planet we know of that supports life. It is home to over seven billion humans and at least ten million species of animals and plants. Of its surface area, 29 per cent is land, and humans have divided that 148,326,000 square kilometres into 196 countries, although this number is disputed. Within these boundaries, reflecting the vagaries of 10,000 years of human history, there are over 4000 religions. Some want to increase the number of countries; others want to decrease the number of religions. For such a small world orbiting an ordinary star in such a run-of-the-mill galaxy, its not very well organised and difficult to understand through the parochial fog. Just over five hundred humans have travelled high enough to see our home in its entirety a small world against the backdrop of the stars and when they do, something interesting happens. They see through the fog, and return with a description not of segregation and complexity, but of unity and simplicity.

When youre finally up at the Moon looking back on Earth, all those differences and nationalistic traits are pretty well going to blend, and youre going to get a concept that maybe this really is one world and why the hell cant we learn to live together like decent people.

Frank Borman, Gemini 7, Apollo 8

Earthrise possibly the most influential and best-known image in space history. Taken by astronaut William Anders in 1968 during the Apollo 8 mission.

If somebody had said before the flight, Are you going to get carried away looking at the Earth from the Moon? I would have said, No, no way. But yet when I first looked back at the Earth, standing on the Moon, I cried.

Alan Shepard, Mercury 3, Apollo 14

Alan Shepard became the first American in space but didnt walk on the Moon until 15 February 1971, with Edgar Mitchell.