The East Garden, designed during the Wilson administration by Beatrix Farrand, in a 1921 photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston.

All the Presidents Gardens

Madisons Cabbages to Kennedys RosesHow the White House Grounds Have Grown with America

Marta McDowell

TIMBER PRESS

PORTLAND, OREGON

This 1899 cover of the Iowa Seed Company catalog featured the White House, Old Glory geraniums, and elaborate pattern bedding, as well as the forty-five-star flag that flew from 1896 to 1907.

Contents

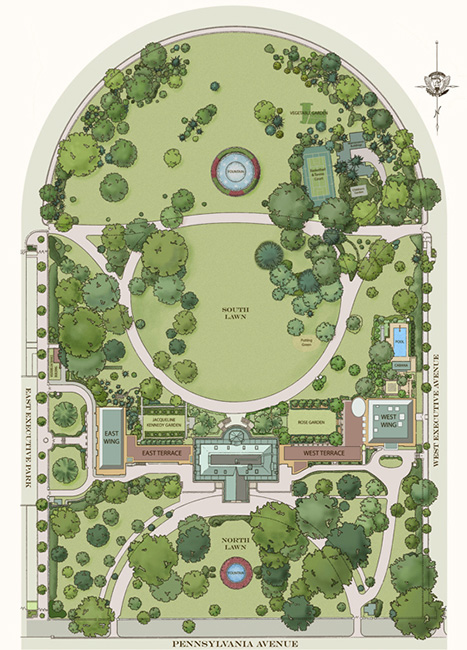

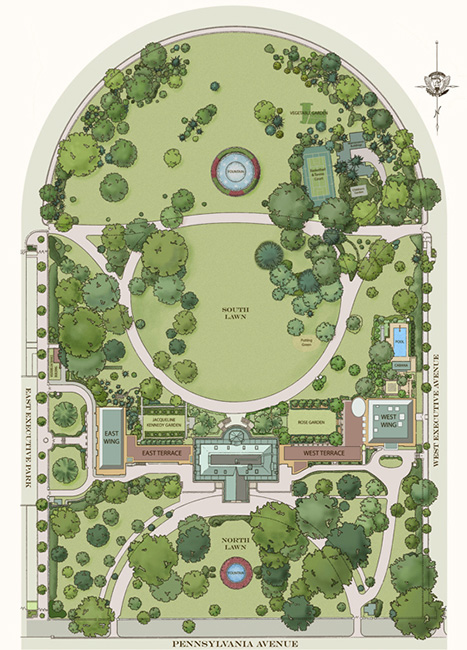

The White House grounds.

Preface

The United States was too big. For a topic, that is. When my editor suggested I might write a history of American gardening, I sat at my desk. Stunned. It seemed a subject broad as a sea of grass, long and muddy as the Mississippi, elusive as a white whale that would, after a mad, obsessed chase, drag me under.

Regional differences are vast. What grows happily for friends in Denver sulks, then dies, in my humid New Jersey garden. Then there are questions of influence that vary across the wide waist of the continent: the Spanish with their patio and courtyard gardens from Florida to California, the tidy colonial gardens of New England, the immense plantations of the antebellum South. And with more than five-plus centuries, depending on how you count, the players involved in American horticulture and landscape design are legion.

Two people convinced me to take on this questone dead, one alive. The reason I study, teach, and write about garden history is because of Beatrix Jones Farrand (18721959). On my first visit to the grounds of Dumbarton Oaks in Georgetown in the 1980s, I was smitten with it and Farrand, its designer, one of the countrys first landscape architects. It was about Beatrix Farrand that I taught my first class at the New York Botanical Garden.

Some years later one of my landscape history students, Seamus Maclennan, chose the White House grounds as the topic for his final project. It was riveting, a fifteen-minute chronicle of change in one of Americas most recognizable landscapes. There were victory gardens and flowerbeds, glasshouses and putting greens, all set in the context of American history. For the problem now before me, it would set bounds, but also pull in a cast of characters and a vip setting. Before I embarked on this undertaking Seamus graciously gave me leave to use his idea, proving once again, if you want to hum along with the Rodgers and Hammerstein tune, that if you become a teacher, by your pupils youll be taught.

The lower 48.

Even with this approach, given the number of presidents plus first ladies, gardeners, architects, and the like, Ive had to impose some economies in terms of scope. If, for example, Zachary Taylor is your favorite president, you will be disappointed. As neither he nor his wife were involved in the White House gardens, they do not appear in the narrative. Summer White at the back of the book.

I have defaulted to common names of plants in the body of the book. For those who prefer proper botanical nomenclature, you will find it in a back section, . If you had hoped for a complete list of plants named for presidents and first ladies, I did too. Unfortunately in most cases these cultivars have not stood the test of time, at least in terms of the marketplace. A rhododendron named Mrs. Grover Cleveland might have been a big seller in the 1890s but soon disappeared from the nursery trade.

Long-term White House head gardener Irvin Williams once said, Whats great about the job is that our trees, our plants, our shrubs, know nothing about politics. Despite the presidential focus of the book, I have attempted to emulate the politics of plants. Because whether gardeners lean right or left, blue or red, we are united by a love of green growing things and the land in which they grow.

The variety of corn raised by Native Americans and earlier settlers is still called Indian corn. From Histoire naturelle, agricole et conomique du mais by Matthieu Bonafous, 1836.

PROLOGUE

The Pursuit of Happiness

Since 1800, the white house has served as a residence for the president of the United States. The eighteen acres that surround the White House have been the Forrest Gump of gardensan unwitting witness to historya backdrop for Civil War soldiers, suffragettes, protestors in the 1960s, and activists today. Kings and queens have dined there. Bills and treaties have been signed. On its lawn presidents have landed and retreated. The front and back yard for the first family, it is by extension the nations first garden.

The White House gardens mirror the countrys horticultural aspirations over time. If melting pot has been a persistent metaphor for American culture, American horticulture shares the pedigree. The garden styles of the colonies, and later the United States, were borrowed from Europe and farther afield and then shaped by local traditions, by geography and climate, by transportation, economics, and innovation.

The White House that we know today was not in the mind of English explorer John Smith when he first sailed up the Patawomeck on a June day in 1608. When the wooden boat turned from the Chesapeake Bay into the mouth of the broad river, he and his fourteen-man crew were looking for the passage to the South Seas. Instead they found forests, fish, and farms. Along the Potomac that summer, they encountered native villages and with the villages, gardens bearing their summer abundance.

Corn was the main crop. Not the juicy sweet ears to which we have become accustomed, but Indian corn: hard kernels that had to be soaked or ground. It sustained life during the hungry season. Other food crops were also in evidence: beans, squash, sunflowers, and goosefoot (a relative of quinoa), and, for smoking rather than eating, tobacco. To his London Company John Smith wrote, Heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for mans habitation... were it fully manured and inhabited by an industrious people.

Industrious settlers soon followed, pursuing not so much happiness as the right to plant and cash in on the brown gold that was tobacco. George Washingtons ancestors were among those who emigrated from England and settled in the rich Virginia countryside below the Great Falls of the Potomac. The subjects of the Court of St. James, as well as the rest of Europe, presumed an unquestioned cultural superiority over the native people and a God-given right to improve this new land.

When the Potomac shoreline that John Smith had explored was finally chosen as the capital city of the brand-new United States of America, George Washington knew it needed a place for the president to call home. And that home would need a garden. This book is the story of that garden, and a story of gardening American-style.

Next page

![McDowell - God-Breathed]: the Undeniable Power and Reliability of Scripture](/uploads/posts/book/219249/thumbs/mcdowell-god-breathed-the-undeniable-power-and.jpg)