ALS o BY MICHAEL CHAB o N

Summerland

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

Wonder Boys

Werewolves in Their Youth

A Model World and Other Stories

The Mysteries of Pittsburgh

C o PYRIGHT

First published in a slightly different form in The Paris Review in 2003.

The steadfast generosity of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle enabled the author to begin this novella; that of the MacDowell Colony enabled him to complete it.

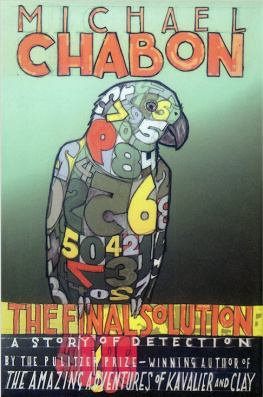

THE FINAL SOLUTION . Copyright 2004 by Michael Chabon.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022.

HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write: Special Markets Department, HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022.

The epigraph is taken from Alternating Currents, in A Kiss in Space: Poems by Mary Jo Salter. Knopf, 1999.

FIRST U.S. EDITION

Printed on acid-free paper

Book design by Jennifer Ann Daddio

Illustrations by Jay Ryan

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

is available upon request.

ISBN 0-06-076340-X

DEDIC a TION

To the memory of

AM a NDA D a VIS

first reader or these pages

EPIGR a PH

The distinctions always fine

between detection and invention.

MARY JO SALTER

C o NTENTS

1

A boy with a parrot on his shoulder was walking along the railway tracks. His gait was dreamy and he swung a daisy as he went. With each step the boy dragged his toes in the rail bed, as if measuring out his journey with careful ruled marks of his shoetops in the gravel. It was midsummer, and there was something about the black hair and pale face of the boy against the green unfurling flag of the downs beyond, the rolling white eye of the daisy, the knobby knees in their short pants, the self-important air of the handsome gray parrot with its savage red tail feather, that charmed the old man as he watched them go by. Charmed him, or aroused his sensea faculty at one time renowned throughout Europeof promising anomaly.

The old man lowered the latest number of The British Bee Journal to the rug of Shetland wool that was spread across his own knobby but far from charming knees, and brought the long bones of his face closer to the window-pane. The tracksa spur of the Brighton-Eastbourne line, electrified in the late twenties with the consolidation of the Southern Railway routesran along an embankment a hundred yards to the north of the cottage, between the concrete posts of a wire fence. It was ancient glass the old man peered through, rich with ripples and bubbles that twisted and toyed with the world outside. Yet even through this distorting pane it seemed to the old man that he had never before glimpsed two beings more intimate in their parsimonious sharing of a sunny summer afternoon than these.

He was struck, as well, by their apparent silence. It seemed probable to him that in any given grouping of an African gray parrota notoriously prolix speciesand a boy of nine or ten, at any given moment, one or the other of them ought to be talking. Here was another anomaly. As for what it promised, this the old manthough he had once made his fortune and his reputation through a long and brilliant series of extrapolations from unlikely groupings of factscould not, could never, have begun to foretell.

As he came nearly in line with the old mans window, some one hundred yards away, the boy stopped. He turned his narrow back to the old man as if he could feel the latters gaze upon him. The parrot glanced first to the east, then to the west, with a strangely furtive air. The boy was up to something. A hunching of the shoulders, an anticipatory flexing of the knees. It was some mysterious businessdistant in time but deeply familiaryes

the toothless clockwork engaged; the unstrung Steinway sounded: the conductor rail.

Even on a sultry afternoon like this one, when cold and damp did not trouble the hinges of his skeleton, it could be a lengthy undertaking, done properly, to rise from his chair, negotiate the shifting piles of ancient-bachelor clutternewspapers both cheap and of quality, trousers, bottles of salve and liver pills, learned annals and quarterlies, plates of crumbsthat made treacherous the crossing of his parlor, and open his front door to the world. Indeed the daunting prospect of the journey from armchair to doorstep was among the reasons for his lack of commerce with the world, on the rare occasions when the world, gingerly taking hold of the brass door-knocker wrought in the hostile form of a giant Apis dorsata, came calling. Nine visitors out of ten he would sit, listening to the bemused mutterings and fumblings at the door, reminding himself that there were few now living for whom he would willingly risk catching the toe of his slipper in the hearth rug and spilling the scant remainder of his life across the cold stone floor. But as the boy with the parrot on his shoulder prepared to link his) own modest puddle of electrons to the torrent of them being pumped along the conductor, or third, rail from the Southern Railway power plant on the Ouse outside of Lewes, the old man hoisted himself from his chair with such unaccustomed alacrity that the bones of his left hip produced a disturbing scrape. Lap rug and journal slid to the floor.

He wavered a moment, groping already for the door latch, though he still had to cross the entire room to reach it. His failing arterial system labored to supply his suddenly skybound brain with useful blood. His ears rang and his knees ached and his feet were plagued with stinging. He lurched, with a haste that struck him as positively giddy, toward the door, and jerked it open, somehow injuring, as he did so, the nail of his right forefinger.

You, boy! he called, and even to his own ears his voice sounded querulous, wheezy, even a touch demented. Stop that at once!

The boy turned. With one hand he clutched at the fly of his trousers. With the other he cast aside the daisy. The parrot sidestepped across the boys shoulders to the back of his head, as if taking shelter there.

Why, do you imagine, is there a fence? the old man said, aware that the barrier fences had not been maintained since the war began and were in poor condition for ten miles in either direction. For pitys sake, youd be fried like a smelt! As he hobbled across his dooryard toward the boy on the tracks, he took no note of the savage pounding of his heart. Or rather he noted it with anxiety and then covered the anxiety with a hard remark. One can only imagine the stench.

Flower discarded, valuables restored with a zip to their lodging, the boy stood motionless. He held out to the old man a face as wan and empty as the bottom of a beggars tin cup. The old man could hear the flatted chiming of milk cans at Satterlees farm a quarter mile off, the agitated rustle of the housemartins under his own eaves, and, as always, the ceaseless machination of the hives. The boy shifted from one foot to the other, as if searching for an appropriate response. He opened his mouth, and closed it again. It was the parrot who finally spoke.

Zwei eins sieben fnf vier sieben drei, the parrot said, in a soft, oddly breathy voice, with the slightest hint of a lisp. The boy stood, as if listening to the parrots statement, though his expression did not deepen or complicate. Vier acht vier neun eins eins sieben.

The old man blinked. The German numbers were so unexpected, literally so outlandish, that for a moment they registered only as a series of uncanny noises, savage avian utterances devoid of any sense.