All rights reserved.

First published in North America, October 2018 by Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers is an imprint of Running Press, a division of Hachette Book Group. The Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.HachetteSpeakersBureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

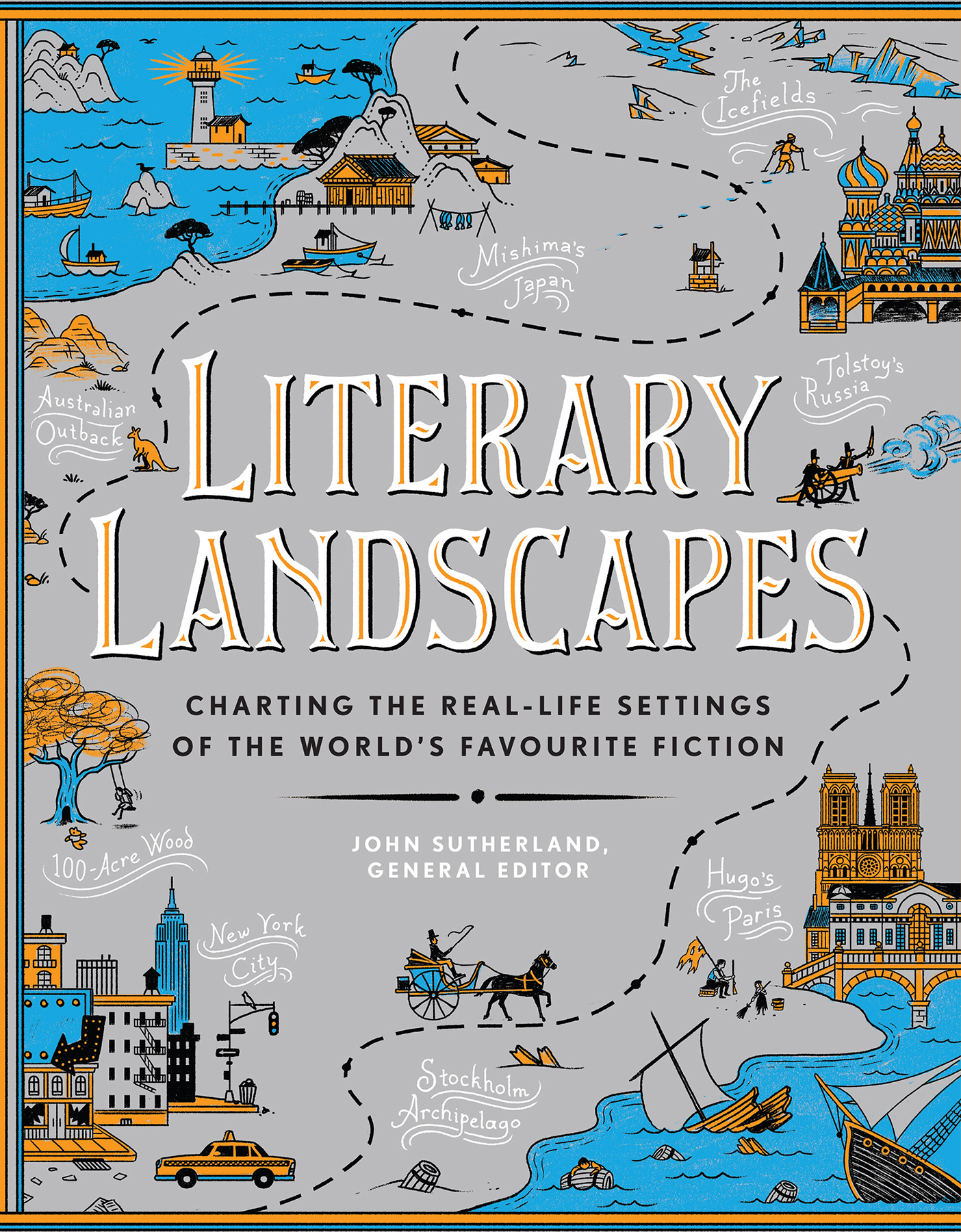

Cover copyright 2018 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

There is no there there, Gertrude Stein, now by choice a Parisian, once wrote, haughtily, of her home city Oakland. These are words that could not be said of any of the books examined and described in this volume. Indicating that Californian citys historical emptiness, positing the location as, disappointingly, a kind of anywhere, with no features to mark it out as either memorable or categorically distinct, Stein gives us a scornful shorthand for defining the elusive sense of place: an essential thereness or isness, without which a citys edges fall apart.

Immediately ones mind starts questioning the idea, subverting it. Was Oakland, when Stein was brought up there (where her childhood was, as Philip Larkin said of his hometown, unspent) the same as where the hippy revolution of the 1960s found its home? Did the Beatniks give Oakland a there which wasnt there, and couldnt be foreseen, in Steins childhood? Is Cannery Row still what the name describes as when fish are canned elsewhere and the place lives mainly as a shrine to lovers of John Steinbecks fiction? This, and many other questions on literary topography, are pondered, illuminatingly and informatively, in the essays that follow.

As a collection of the worlds most memorable fictionalized geographies, Literary Landscapes can be summed up as an investigation into Steins therenessthe enduring fixity of place (Therell always be an England) and the fluidities and meltingness that places are subject to. They melt and reform themselves, over social time, historical time, and geological time. Describing literary place, in the dimensions of time and space, requires a fine critical touchwhich, one can confidently assert, is displayed in the pages that follow.

All the works described in this volume capture, are even built upon, a sense of their authors having been to, seen, experienced, and been able to relate all the qualities of a place that, in combination, lodge that locale in cultural and geographical specificity. From Hardys Wessex to Mishimas Japan, from Bulgakovs Moscow to Proulxs Newfoundland, the literary landscapes collected here are singular in their sights, sounds, associations, and representations; they could not be mistaken for anywhere else.

The idea of literary landscape was, originally, founded on a paradox. Entering the English language as a loan word by way of the Dutch landschap in the early seventeenth century, a landscape initially denoted a purely visual representation. The natural world had begun to emerge from its position as an undervalued backdrop, becoming a major artistic genre from Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin onward, but its depiction was a pictorial skill.

By contrast, literary landscape, the subject of this richly detailed and illustrated volume, cannot, like fine art, be experienced as representation by the eye alone. Literary landscape is composed of words which must be recomposed in a frame of imagination. The inward eye, British Lakeland poet William Wordsworth called it, drawing a distinction between perception and imagination. Just as the painter can choose his balance of verisimilitudestriving for eye-witnessed accuracyand creative depiction, so the writer must decide how much of an influence his inward eye will have on the scene depicted. What one might call creative bias comes into itsubjective coloration. And sometimes moral judgement: when Bunyan called London Vanity Fair (a place of ostentation or empty, idle amusement and frivolity) he meant something quite different, morally, from what London-loving William Makepeace Thackeray presents in his novel Vanity Fair. Thackeray rather liked amusement and frivolity.

Some writers open up more than others to the demands of imagination combining studious historical research with the literary artists creative licenceChinua Achebes chronicle of pre-colonial life in Nigeria, for instance (1958, ) hovers between fact and fictioncreating a landscape at once familiar and foreign, populated by phantoms.

For others, a more photographically exact portrayal of place yields a greater reward. Often these writers draw upon a personal topography, recreating the intimate corners of their own uniquely felt experience. From August Strindberg, whose Hems was recognized as a lightly veiled version of Kymmend where he had spent his childhood summers (1887, ), personal biography informs and colors these characterizations of place and renders them all the more fascinating because of that.

Sometimes authors choose to work on a large canvas landscape, powerful and dramatic, dwarfing humanity; others work on a smaller scale. Jane Austen, whose novel Persuasion (1817, nature as she really exists in the common walks of life, and presenting to the reader, instead of the splendid scenes from an imaginary world, a correct and striking representation of that which is daily taking place around him. Yet, even the little bit (two inches wide) of ivory, as she called it, on which she wrote can give us an occasional large canvas landscape. One such is in the Donwell Abbey Picnic scene in Emma. The picnickers have nothing much to say to one another, and Emma looks down from the hill on which she is standing:

half a mile, at the ruined Abbey and the Abbey Mill farm. It was a sweet viewsweet to the eye and mind. English verdure, English culture, English comfort, seen under a bright sun, without being oppressive.

What is Austen saying here in her encomium of the Englishness of the sweet landscape? Emma Woodhouse has this serene confidence that her countrys countryside was the best anywhere in the world: the dates tell us that these were ominous years for Anglo-French relations, with Waterloo, Napoleons exile, victory, then peace and the inauguration of the British Century. Not even a parsons daughter in rural Hampshire could be unaware that society was changing. In short, this is an exquisitely described landscapeworthy of the miniature ivory artistwith a heavy historical subtext to it. Though rooted in her own observation, the novel becomes a commentary on a world beyond personal experience, as a vehicle for affirming Englishness.