Thank you for buying this ebook, published by HachetteDigital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about ourlatest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

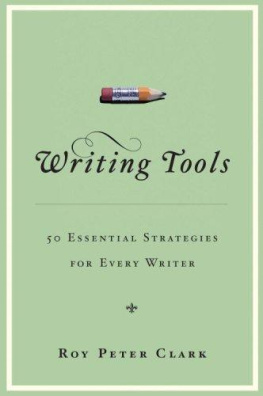

Copyright 2016 by Roy Peter Clark

Cover design by Keith Hayes

Cover copyright 2016 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Author photograph by Kenny Irby

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: January 2016

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The author is grateful for permission to reprint the following:

Excerpt from Daddy from Ariel by Sylvia Plath. Copyright 1963 by Ted Hughes. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Excerpts from The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. Copyright 1971 by Harper & Row, Publishers. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Excerpt from Hiroshima by John Hersey. Copyright 1946, 1985, copyright renewed 1973 by John Hersey. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from Miss Lonelyhearts & The Day of the Locust by Nathanael West. Copyright 1939 by Estate of Nathanael West. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

All excerpts from The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald are taken from the 2004 Scribner edition, which is published by Simon & Schuster.

ISBN 978-0-316-28216-1

E3

To my brothers, Vincent Clark and Ted Clark, for their tender care of our mom, Shirley Clark, who, at age ninety-five, was still singing.

Where do writers learn their best moves? They learn them from a technique I call X-ray reading. They read for information or vicarious experience or pleasure, as we all do. But in their reading, they see something more. Its as if they had a third eye or a pair of X-ray glasses like the ones advertised years ago in comic books.

This special vision allows them to see beneath the surface of the text. There they observe the machinery of making meaning, invisible to the rest of us. Through a form of reverse engineering, a good phrase used by scholar Steven Pinker, they see the moving parts, the strategies that create the effects we experience from the pageeffects such as clarity, suspense, humor, epiphany, and pain. These working parts are then stored in the writers toolshed in boxes with names such as grammar, syntax, punctuation, spelling, semantics, etymology, poetics, and that big boxrhetoric.

Lets get to work.

Please put on your new X-ray reading glasses so we can examine the titles of a couple of famous literary works. The first is The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1915), by T. S. Eliot. (The poet died in 1965, my senior year in high school, when I became the keyboard player in a rock band called T. S. and the Eliots.)

Prufrock is widely considered one of the great poems of the twentieth century, and I encourage you to read it for the first time, or again, to see if my claims about the title ring true. The poem is, most of all, a poignant reflection on the losses brought on by aging. The protagonist is torn between the lingering longings of youthromance, sexual energy, creativity, social prominenceand his sense of himself as an old man. He wonders if women at social gatherings, discussing Michelangelo, will notice him; he shrinks in stature and wears his pants rolled up at the cuffs; he worries whether his dentures will allow him to eat a peach. He looks back to see how his life has been measured out, a wonderful poetic phrase, and all he can see is coffee spoons.

Those are the dramatic and thematic outlines of the poem, but how did Eliot create them? If we can answer that question, perhaps we can begin to know some of the things he knew as a writer. Maybe there will come a time when we can reach for that knowledge and write a title to a text that draws on the same creative energy used by Eliot.

So what is the source of that energy?

My X-ray vision reveals that The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock is a title built upon a tension, a friction, a rub between two dramatically different phrases, two radically different kinds of language.

Write down some of the associations you make when you hear the phrase love song. My list contains courtship, romance, flirtation, beauty, serenade, youthful exuberance, hope, longing, music, poetry. The range of associationswriters call them connotationscan be wide. A Shakespeare sonnet is a love song: My love shall in my verse ever live young. But so is Double Shot (Of My Babys Love), by the Swingin Medallions.

So who is the persona created by Eliot to sing his love song? Does he have a poetic name such as Marvell, Wordsworth, or Longfellow? No: his name is J. Alfred Prufrock. Make a list of things that come to mind when you read or hear that name. My list includes banker, academic, attorney, businessman, bureaucrat. Nothing defies romance like a name that begins with a first initial followed by a full middle name. John A. Prufrock sounds more regular than J. Alfred Prufrock, which tiptoes near a parody of cold British fussiness. And then there is Prufrock, a name in full defiance of love song. Passion and fervor are neutralized by the empiricism of Pruf (proof) anchored to the hardness of rock. Read another way, that last name might divide as Pru-frocksomeone who wears prudish or prune-ish garb, a shrinking old man who wears his trousers rolled up so he wont step on them.

The tension can be felt in the very letters. The first phraselove songhooks up the liquid consonant l with the sexy sibilance of s. In contrast, Prufrock links a plosive p with the fricative k sound. Combined, the effect is like a great wave of sea and sand crashing onto a boulder-blocked shore.

See what happens when you put on those X-ray glasses? You are cured of the myopia of common reading. Beyond clarity, you gain an inner vision of literary effects, at its best psychedelic, kaleidoscopic, and 3-D. You are beginning to see as a writer.