PENGUIN BOOKS

A PLACE OF MY OWN

Michael Pollan is the author of five books, including In Defense of Food, The Omnivores Dilemma , and The Botany of Desire , all New York Times bestsellers. A longtime contributing writer to The New York Times Magazine , he is also currently the Knight Professor of Journalism at the University of California at Berkeley. To read more of his work, go to www.michaelpollan.com.

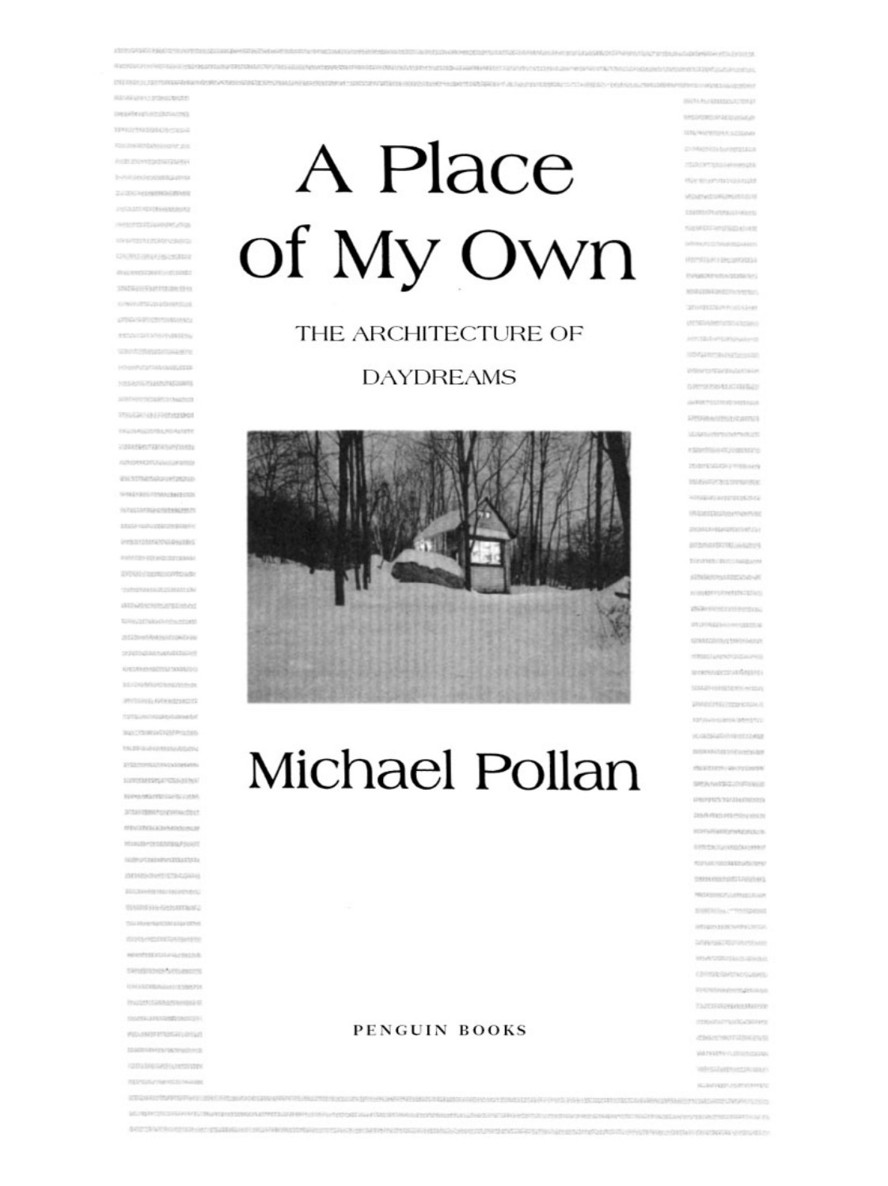

A Place of My Own

THE ARCHITECTURE OF DAYDREAMS

Michael Pollan

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

First published in the United States of America by Random House, Inc., 1997

Published by arrangement with Random House, Inc.

This edition with a new preface published in Penguin Books 2008

Copyright Michael Pollan, 1997, 2008

Drawings copyright by Charles R. Myer & Company, 1997

All rights reserved

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Pollan, Michael.

A place of my own: the education of an amateur building / by Michael Pollan.

p. cm.

ISBN: 1-4406-5564-2

1. HutsDesign and constructionPopular works. 2. Space and timePopular works. I. Title.

TH4890.P65 1997 690.837dc20 96-35101

Title page photo copyright 1997 by John Peden

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

For Isaac

With this more substantial shelter about me, I had made some progress toward settling in the world.Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Contents

Preface

A Place of My Own is the biography of a building. In a sense it is the biography of every building, but happens to dwell on one in particular: the not-so-primitive hut I built in the woods behind my house in New England, as a place to read and write and daydream. This is not a famous or important building, but to me it has meant the world: I built it with my own two unhandy hands, and it is in here I wrote the book you now hold, as well as a second ( The Botany of Desire ) and a third of a third ( The Omnivores Dilemma ).

But the book could have been written about almost any building because at its heart is a narrative of the universal process of design and constructionwhich is to say, the age-old story of how dreams get turned into drawings that then get turned into wood and stone and glass, finally to take their place in the palpable world. I have always found that process wonderful and slightly mysterious, and the people involvedarchitects and buildersparticularly impressive characters. Architects do their work on the frontier between the ideal and the practical, translating wisps of ideas into buildable facts, and carpenters are among those lucky souls whose handiwork actually adds to the available stock of reality. To a writer, whose creations can really only be said to exist among the human speakers of his or her language, this is cause for envy. For us, terms like architecture and carpentry are little more than pretentious metaphors we use to dress up our far more ephemeral makings.

I had a dense tangle of reasons for wanting to build something, but one of them was to join the world of the makers homo faber and leave, if only temporarily, the dodgier world of words. I was looking for an antidote to the increasingly abstract and abstracted nature of my altogether typical working life, most of which was conducted in front of screens at an ever-greater remove from the natural world. Its possible I was also in the midst of a low-grade midlife crisis, and may have been looking for an escape hatch from a house that had mysteriously begun to shrink with the arrival of a new baby.

All this is true enough. But I also wanted very simply to learn how the work gets done: how exactly a designer goes about designing a successful space and a builder building it. At first I thought I could learn this by following the design and construction of a house or perhaps a skyscraper, and I started out on such a path. But I found I couldnt get as close to the subject and the work as I wanted to, and eventually realized I could learn a lot more by radically shrinking the dimensions of the project, stripping it down to its essentials and to a scale where I could work on it with my own hands right in my own backyard, as it were. In other words, I decided to conceive and build a microcosm: a place of my own that would also be a tool for exploring architecture.

It wasnt until I started down this path that I learned that the history of architecture contains a rich tradition of such microcosmsstories about elemental buildings conceived as a way to return architecture to its first principles. Beginning with the Primitive Hut described by the Roman architect and writer Vitruvius, accounts of the First Shelter have served as myths of the origins of architecture, as well as clever ways to argue for your particular view of how buildings should look and be built. Vitruvius primitive hut looks a lot like a Greek temple built out of tree trunks and branches, thereby implying that the classical forms he admires were given to us by the forest itself, and so have the sanction of nature. Following his example, Alberti, Laugier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier each constructed (at least in words) their own rhetorical hut as a way to argue for the naturalness or inevitability of their respective visions of architectureneoclassical, Gothic, modern, whatever. In much the same way, many writers have built their own primitive hutsthink of the ones in Robinson Crusoe or Walden as a vantage from which to explore civilized mans relationship to nature and launch their critiques of modern society.

In retrospect I can see that my little cabin by the pond in Connecticut, and this account of it, is very much in the tradition of the Polemical Hut. In the course of its narrative, A Place of My Own puts forth an argument about architecture as well as modern life and work, all of which, I suggest, have lost the vital thread of their connection to nature, much to the detriment of our lives and buildings.

Next page