O urs is a small, rural Scottish town. There are shops, parks, a school, and a Victorian museum which displays, amongst other things, a two-headed weasel and a Zulu shield. Stolid stone houses, some painted a grudging cream or pale blue, line a long main street. There are no front gardens. Its the kind of place where you acknowledge the people you pass. There is too much traffic, always going elsewhere.

Because it was Guy Fawkes night, we were going to buy fireworks . The kids ran ahead, while I walked past six or seven houses, all with lace curtains, all with closed doors. When the doors are closed, the town can take on a dour, forbidding look. From The Tay View came a sudden male roar. Rangers must have been winning the football.

The kids were excited about their fireworks. They were going to have friends over, and eat sausages.Wed left their dad building a bonfire at the top of our long garden. They danced on ahead toward the Post Office cum toyshop.

Beyond the Co-Op the pavement widens out to accommodate a flowerbed and a couple of benches.And there, in a circle, cross-legged on the pavement, were a dozen Pakistani men.

The impression was all of textile, of fabric. They were sitting on a brightly patterned cloth, they wore white turbans, green bandannas and beards, and baggy shalwar-kameez, with anoraks and leather blouson jackets against the Scottish cold. One had a fine brown blanket draped over his head and shoulders. Another, a little bright green mirror-work hat. The youngest was a doe-eyed lad of about twenty with a few wisps of beard, the eldest would be about fifty, a doughty, confident personage we came to know as Mahmood. I say cross-legged, but one of the men was kneeling, with his back to the road, swaying back and forth as he read aloud from the Quran.

Duncan came running back to me.

Mummy! Come on! Lets get our fireworks!

In a minute

No, Mummy, come on!

We bought the fireworks, and a paper, and some milk. The paper had a front-page picture of an Afghan woman in a pale blue burqa. These men could easily have been taken for Afghanis, maybe thats why no one seemed quite sure what to do with them. No one seemed to have approached them, though a couple of women in tweed coats stood at the bus stop, talking in low voices.

With a child in either hand, I made a move, and two of the men clambered to their feet.

A-salaam aleikum, I said.

Aleikum a-salaam!

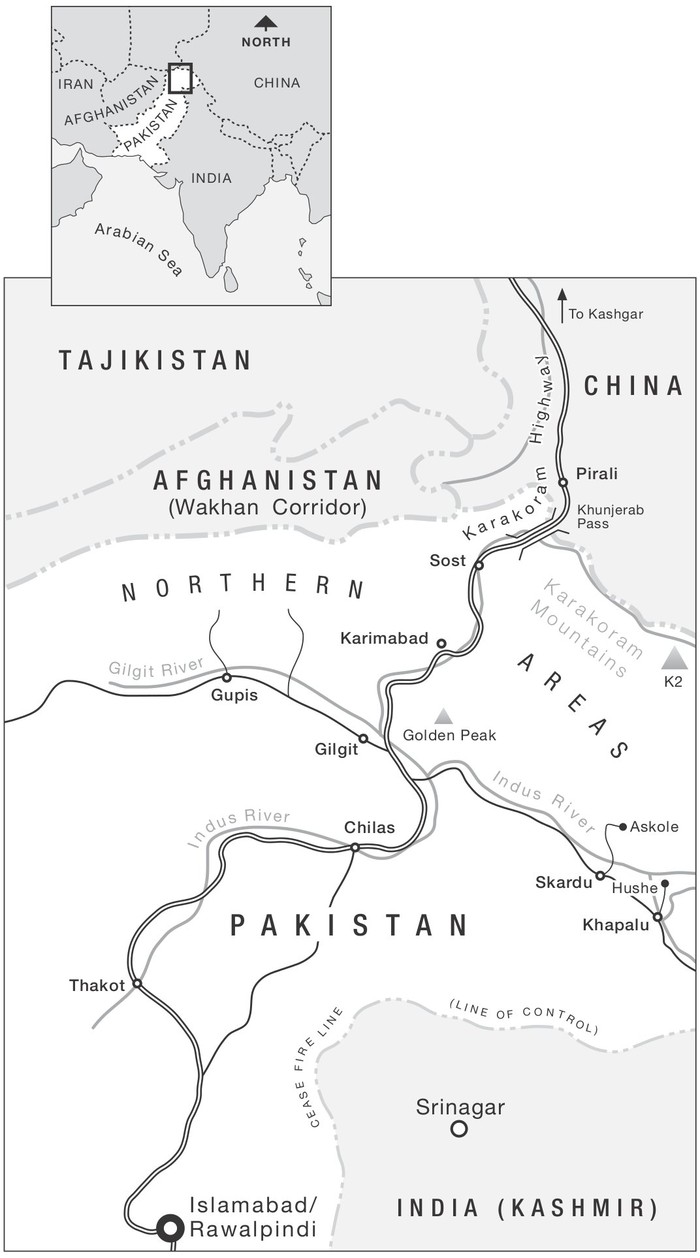

Since the war in Afghanistan Id been thinking a great deal about Pakistan. The TV news carried nightly reports from Islamabad and Peshawar and Quetta. There were refugees and anti-US riots, and once, the BBC even suggested that the road into the Northern Areas, the Karakoram Highway, was in the hands of the Taliban, but I didnt believe it.

It was ten years since Id last been there, and although wed lost touch, Id written a letter of concern to the women who had befriended me in the northern town of Gilgit, but they keep purdah, and it was all a long time ago, and I didnt really expect a reply.

All the men in the circle were looking at us. They smiled and nodded.

Youre from Pakistan! Im pleased to meet you, I said, and held out my hand, but the man with the green bandanna backed off from it, smiling and bowing.

The two tweedy women had ceased talking to watch.

And thats how come we went out for fireworks and came home with three Punjabi men in full fig. I was wearing my frump-at-home dark blue skirt, which reaches almost to my ankles, and, for once, was glad of it. Id mustered my few words of Urdu: tea, house, husband; and three accepted.We made a jolly party, striding up the pavement, exchanging names, and fussing over the children. They made an enormous fuss over the children. The wind tugged their turbans and shirt-tails.

We led the men through the green gate which leads into our yard, and I sent Duncan up through the garden to find his dad, while the rest of the party followed.

The gardens are our towns best kept secret. Behind the closed doors and the dour privacy of the street are plum orchards and apple orchards, sunlit lawns, bee-hives and vegetable plots, and views of the wide, blue Firth of Tay and the Carse of Gowrie to the north. Walls and fences are little more than a gesture, everyone just knows whose is whose, so the impression you have is of sunlit openness. The three Pakistani men stood under the plum trees and exclaimed. They turned, exclaiming about the sudden view of the river. I wanted to tell them that it was the same, that when I myself had been admitted through the austere green street-gates of Gilgit, I had found gardens and vegetable plots, family compounds, children, and an insistent hospitality.

Phil came striding down. In his younger, mountaineering days, he too had spent time in Pakistan, but that was before we met. We often spoke about the place, and promised ourselves that one day, when the kids were much older, wed go back.

The men shook hands and exchanged names. The biggest, with the black beard, he was Mahmood.He was, he said, a miner, but that was disingenuous. His card, which he flourished from an inner pocket, named him as chief executive of five mineral-extraction businesses in the Punjab. The man called Nazir was thinner, he wore a parka over his shalwar-kameez.

He is the mayor of our town! said Mahmood.

Scotland must seem cold, after the Punjab, I said, but as if to concede that Scotland was cold would be to insult it, Nazir turned his head and smiled.

Not cold. Scotland is very fine. Scottish people very kind.

The third was an older man, who spoke little. He had a kindly, thin face and wore a fine woollen blanket like a shawl over his head and shoulders. I never learned his name.

We ushered our three guests indoors. As they demurred and we fussed, I saw my house through new eyes.What did we have that they would recognise? A decent front room for visitors? No. They were shown into our cramped kitchen. An elegant matching tea set? Fat chance. The cooker hadnt been cleaned for a week. There was much courtesy over chairs, but eventually the three men were seated and I began to make tea, which I knew theyd find insipid and bitter. Sugar. We needed sugar. We needed clean cups. Spoons, why are there never any spoons? I flapped the cat out of the kitchen.

You alright with cats? I asked Mahmood.

Cats, yes. Dogs, he tilted his head. Dogs, no.

They sat at the table. Phil and I stood. The children stared.We named the places in Pakistan wed known, Phil and I. Rawalpindi, Islamabad, and especially, the mountainous Northern Areas It was before the kids were born. The men fussed over the children, toyed politely with their tea, and with courtly gestures refused the shortbread we offered. Everyone was merry. But, we asked, why on earth they were here?

They told us they were on a Peace Walk. They had started in Aberdeen, back in August, and were walking through all the small towns of Scotland, until, at length, they reached Glasgow. It would take, they said, four months. Four months? I glanced down at their shoes. Id been chided in Gilgit for the unladylike state of my own, but theirs were not fit for four months walking in a Scottish winter.

Yes. It is at our own expense. Our purpose is to be here and say to Scottish peoples, we can be understanding. In every town we are making some talk, some communication. Muslim and Western, we are all the Children of Adam, you understand? In every town we arrive, and sit as you saw.

![Kathleen Jamie [Kathleen Jamie] Among Muslims](/uploads/posts/book/141349/thumbs/kathleen-jamie-kathleen-jamie-among-muslims.jpg)