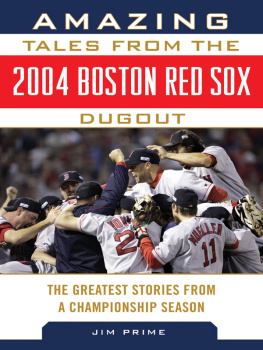

Copyright 2007, 2014, 2019 by Kirby Arnold

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sports Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Sports Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.sportspubbooks.com. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-68358-284-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-68358-287-8

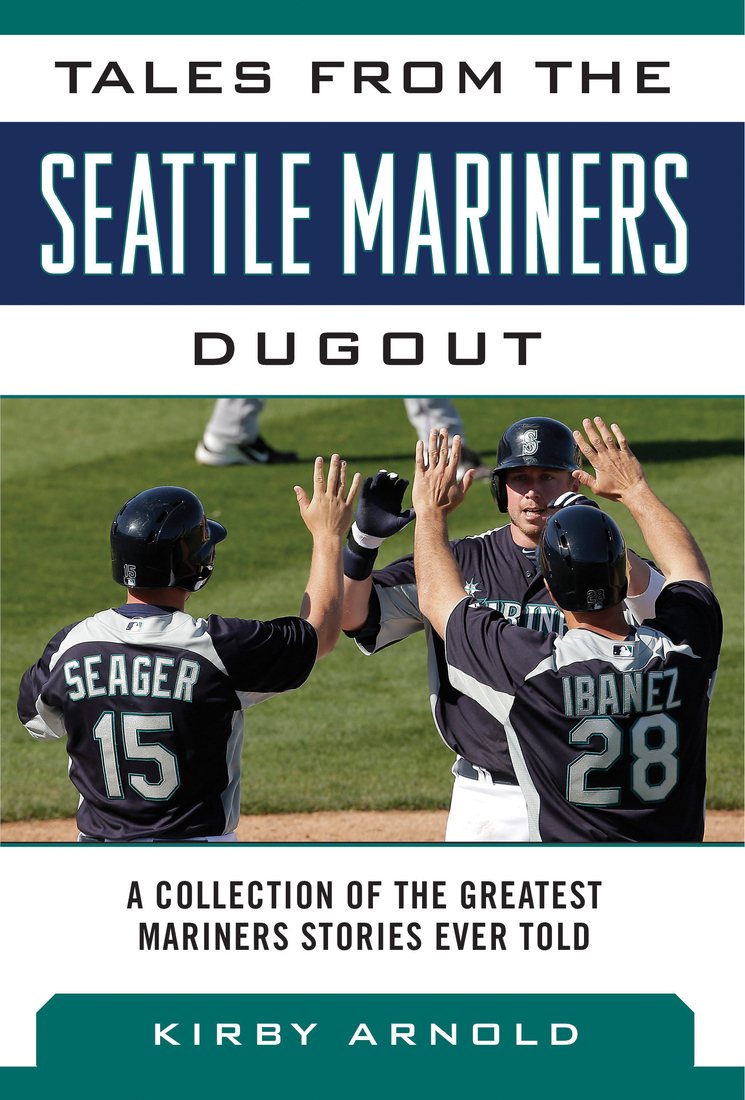

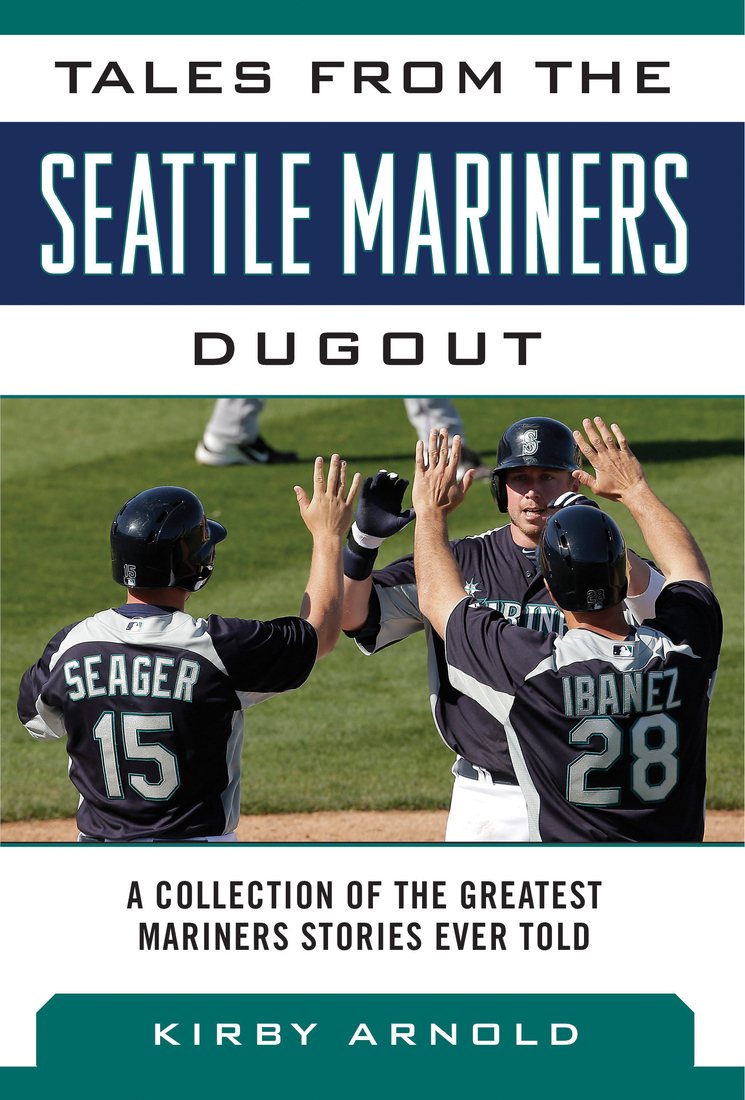

Cover design by Tom Lau

Cover photo Getty Images

Printed in the United States of America

This book is dedicated to my family, which has encouraged and supported me from the day I wrote my first word as a sportswriter.

To my father, whose love of baseball left a permanent imprint on me.

To my mother, who drove me from ballpark to ballpark after I landed my first newspaper job as a 15-year-old without a drivers license.

To my two children and my grandchildren who are the delights of my life.

And most of all, to my wife for her unending love and support of my passion, despite the hours she spent waiting for me in empty high school gyms and the nights at home alone as I worked.

I am truly privileged.

KA

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Baseball in Seattle

WILL IT FLY, OR FLY AWAY?

LEE ELIA NEEDED HIS PREGAME CIGARETTE, so he ducked into a hallway outside the Seattle Mariners clubhouse and lit up.

It was less than an hour before a weeknight game in September, typically an empty-house night in the vast Kingdome. Elia, the Mariners hitting coach, was puffing away that 1995 evening when he peered through an opening that gave him a good view of the stadium. What he saw stunned him.

My God, Elia said to himself. This place is filling up.

He walked back inside the clubhouse and stopped Sam Mejias, the Mariners first-base coach.

Hey Sammy, do we have a promotion tonight? Elia asked.

I dont think so, Lee, Mejias answered. Why?

Well, Elia said, thats not our usual 12 or 13 thousand out there. This place is filling up.

It was a trend in the making. By September of 1995, there was no such thing as a typical weeknight in the Kingdome. The Mariners had found some magic on the field, climbing from 13 games out of first place in the American League West Division in mid-August to contention by mid-September, and theyd done it with a series of two-out rallies and comeback victories that created a buzz in Seattle. For the first time ever, baseball became important in September, and big crowds were watching the Mariners in the Kingdome.

We went back out a little later to take infield practice, and I noticed a little guy out in center field who was holding a sign, Elia said. It read, Refuse to Lose.

Those words became the Mariners battle cry.

I was telling guys, Look at that: Refuse to Lose. You know what? The way were playing, we might not lose this thing, Elia said. I think that night there must have been 30,000 people at that game, and the energy was terrific. You could feel it in the clubhouse, and it never stopped.

Two weeks later, the Mariners were still refusing to lose and, best of all, their growing fan base was on board for a delirious ride that helped prove Seattle is indeed a baseball town. The city had suffered through the loss of the Seattle Pilots after one season in 1969, then nearly two decades of losing seasons and meaningless Septembers by the Mariners. But suddenly, Seattle found baseball worth celebrating.

The Mariners went on to win the 95 American League West Division championship, beating the California Angels 91 in a one-game tiebreaker on October 2. Across the Pacific Northwest, fans reveled over what their team had accomplished. They sported their Mariners hats with pride, and purchased jerseys with the names Griffey, Martinez, Buhner, Johnson, Wilson, Cora, and Piniella on the back. For those final weeks of September, then six playoff games in October, cheering inside the Kingdome had never been louder for baseball, and the enthusiasm throughout the Northwest had never been greater for the Mariners.

Those who had proclaimed for years that Seattle wasnt a baseball townand there were plentycouldnt say that anymore. It only took the Mariners 19 years to prove every naysayer wrong. Since 1977, winning a championship seemed like the remotest of possibilities.

The Mariners were known better for goofy promotions like Funny Nose Glasses Night, which drew a bigger crowd to the Kingdome in 1982 than Gaylord Perry pitching for his 300th career victory did just two nights earlier. Over their first few years, the Mariners offered some memorable moments on the field as well as players who became fan favorites. Their fans cheered good young players such as center fielder Ruppert Jones and second baseman Julio Cruz; but fans also appreciated a prankster like Bill Caudill, a solid closer who had earned the nicknames The Inspector and Cuffs, because of his penchant for handcuffing unsuspecting victimsincluding the owners wife.

Anyone who followed the team in the early years learned not to expect too much, especially late in the season when the games held little meaning. Before 1995, the Mariners were known for small crowds in the Kingdome, where the sound of cheers lingered only because the huge concrete structure allowed plenty of room for echoes to reverberate.

Yet the infant Mariners endured through shaky ownership and fears that they would follow the fate of the Pilots and move away from Seattle. Star players such as Alvin Davis, Mark Langston, Harold Reynolds, Omar Vizquel, Ken Griffey Jr., Randy Johnson, Jay Buhner, Alex Rodriguez, and Edgar Martinez wouldnt come along to pique anyones interest until years later. The early Mariners were a tough sell to the fans, and winning over the media wasnt any easier.

The Struggle for Respect

Randy Adamack was 27 when he joined the Mariners midway through their second season, 1978, as public relations director. He spent many of his first days on the job introducing himself to the media, and among his appointments was a meeting with Georg Meyers, the former sports editor of the Seattle Times. The two talked for a few minutes, and Adamack remembers feeling good about how Meyers received him. The man was pleasant and cordial, and he seemed willing to give baseball a chance, Adamack thought. Then Meyers bluntly ended the meeting with the absolute truth.

Randy, you seem like a nice young man, and I wish you a lot of success, Meyers said. But I have absolutely no interest in baseball. Good luck.

Welcome to Seattle. Have fun trying to make baseball work here. Dont let the football season hit you on the backside.

Next page