ALSO BY HOWARD W. FRENCH

Disappearing Shanghai: Photographs and Poems of an Intimate Way of Life (with Qiu Xiaolong)

A Continent for the Taking:

The Tragedy and Hope of Africa

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2014 by Howard W. French

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

French, Howard W., author.

Chinas second continent : how a million migrants are building a new empire in Africa / Howard W. French.First edition.

pages cm

This is a Borzoi book.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-307-95698-9 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-385-35168-3 (eBook)

1. ChineseAfrica, Sub-Saharan. 2. ImmigrantsAfrica, Sub-Saharan.

3. Africa, Sub-SaharanEmigration and immigration.

4. ChinaEmigration and immigration. I. Title.

DT16.C48F74 2014

325.2510967dc23 2013026930

Jacket design by Jason Booher

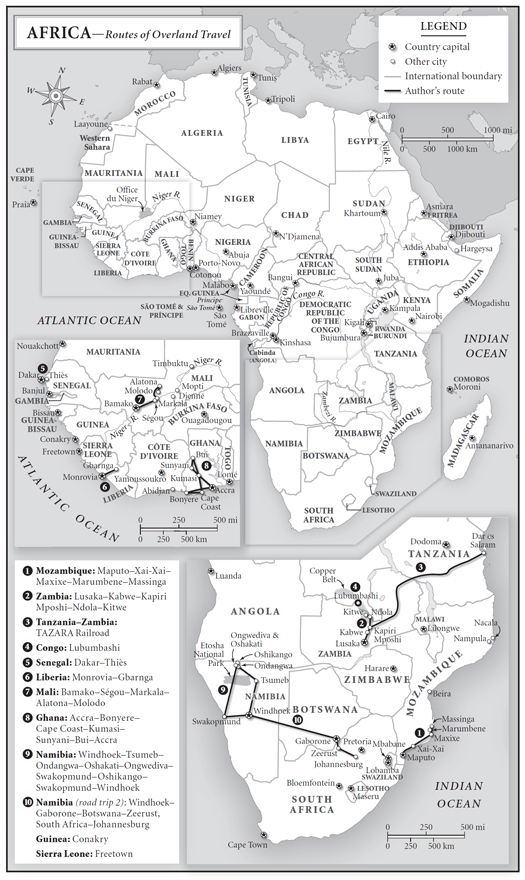

Map by Mapping Specialists, Ltd.

v3.1

In memory of Mary Fine Bread Andoh,

who gave me Avouka,

who begat William and Henry

Alas, journey upon journey

upon journey, were separated

with thousands and thousands

of miles between us, each stranded

at the other end of the world.

The roads so difficult and long,

when can we possibly see

each other again? The horse

from the north still yearns

for the northern wind, the bird

from the south clings, like

before, to the southern branch

FROM JOURNEY UPON JOURNEY , AUTHOR UNKNOWN. HAN DYNASTY CHINA. TRANSLATED BY QIU XIAOLONG .

I could not have told you then that some sun would come,

somewhere over the road,

would come evoking the diamonds

of you, the Black continent

somewhere over the road.

You would not have believed my mouth.

FROM TO THE DIASPORA, GWENDOLYN BROOKS

Introduction

When China launched its historic opening toward the end of the 1970s, the country and its people not only became the fortunate beneficiaries of astute new policies, but alsocruciallyof magnificent timing. The next few years, as they unfolded, would take shape as an era of unprecedented globalization, and no country would profit more from the coming tidal wave of economic change. In little more than a decade, China went from being a poor society with an economy that produced few goods for export and imported little, to positioning itself to become the so-called factory of the world, as we recognize it today.

As great as this era of change proved to be for China and for the Chinese, though, globalization was essentially being carried out on other peoples terms, namely those of the United States, Western Europe, and Japan. The economic powerhouses of the rich world sought new outlets for their surplus capital, as well as low-wage labor for their enterprises, allowing them to ply eager Western consumers with ever-cheaper goods. And for both of these purposes, China fit the bill better than anyplace else on earth.

Modern globalizations first great wave has now crested, and is being overtaken by a newer and potentially even more consequential tide. In this new phase, China has gone from being a vessel to becoming an increasingly transformative actor in its own right. Indeed, it is rapidly emerging as the most important agent of economic change in broad swaths of the world.

Chinese banks, construction companies, and other enterprises in ever growing variety conspicuously roam the planet nowadays in search of outlets for their money and goods, for business and markets, and for the raw materials needed to sustain Chinas rapid growth. As they do so, China is increasingly writing its own rules, and reinventing globalization in its own image, gradually jettisoning many of the norms and conventions used by the United States and Europe throughout their long and hitherto largely unchallenged tutelage of the Third World.

Beijing has achieved this, in part, by engineering a kind of modern-day barter system in which developing countries pay for new railroads, highways, and airports through the guaranteed, long-term supply of hydrocarbons or minerals, thus helping Chinese companies win massive new contracts. In hundreds of other deals, Chinas Export-Import Bank and other big, state-controlled policy bank counterparts have teamed up to offer attractive project financing that is usually tied to the use of Chinese companies, Chinese materials, and Chinese workers.

Africa, more than any other place, has been the great stage for these innovations, and the focus of extraordinary Chinese energy as a rising great power casts its gaze far and wide for opportunity, like never before in its history. Sensing that Africa had been cast aside by the West in the wake of the Cold War, Beijing saw the continent as a perfect proving ground for some Chinese companies to cut their teeth in international business. It certainly did not hurt that Africa was also the repository of an immense share of global resourcesraw materials that were vital both for Chinas extraordinary ongoing industrial expansion and for its across-the-board push for national reconstruction.

As a result, Africa has risen high on Beijings agenda. Indeed, Chinas new leader, Xi Jinping, visited the continent in his very first overseas trip as president, and not a year goes by without multiple visits to the continent by several of the countrys top leaders, marking a stark and I believe deliberate contrast with the United States, for which a presidential or even secretary of states visit to Africa is an infrequent event. For China, this kind of attentionwhat African leaders have called servicing the relationshipcombined with Beijings official largesse, is paying off handsomely. Chinas trade with Africa zoomed to an estimated $200 billion in 2012, a more than twenty-fold increase since the turn of the century, placing it well ahead of the United States or any European country. For a key Chinese industry like construction, meanwhile, African contracts by some estimates now account for nearly a third of its total revenues abroad.

In recent years, developments like these have engendered a lively if often sterile debate about whether Chinas growing engagement will fundamentally help rebuild Africa, placing it on a path to prosperity, or will result instead in a rapacious recolonization in all but name. In most of these debates the conclusions seem largely predetermined, like so many plodding legal briefs: in reflexive defense of China, or equally automatic skepticism toward the country and its intentionscheering for the West and celebrating its values, or full-throated schadenfreude over its every comeuppance.