Table of Contents

For friends in Dawson, then and now

PREFACE

IN 2008, THREE FRIENDS and I rafted down a section of the wide, silty Yukon River in the endless sunlight of four long June days. The scenery was breathtakingno visible human habitations, distant snow-capped mountains under a vast sky, a black bear at the waters edge, and two moose standing motionless in a swamp. Massive log pile-ups littered the riverbanks like timeless sculptures. I heard the croak of ravens, the hiss of river sediment against the rubber raft, the howling wolves. I watched a branch bob along in the water, then realized it was a fifty-foot spruce tree, wrenched from the bank by a current strong enough to carve out new channels and treacherous gravel bars. My fingers went numb when I dipped them into the icy water.

I faced none of the risks and few of the discomforts confronted by those who had made the same journey in the 1890s, during the Klondike Gold Rush. We had life jackets, a Global Positioning System, down sleeping bags, Therm-a-Rests, bug repellent, a four-burner gas cooker, and all the other gear designed for extreme adventurers today. Even though I felt a lifetime away from my family south of the sixtieth parallel, I could return home within a few hours by plane.

Nevertheless, I felt the menacethe sense that we were trespassers on the immense silence. In four days of travel, we saw only three other boats, two of them with Hn men at the tiller. If, with all the protective paraphernalia that we had stowed, I felt overwhelmed by the savage beauty of the surroundings, how much more intense must it have been for those intrepid adventurers at the peak of the Gold Rush? If one of them drowned, it would take months for the news to reach his family back home. If he was alone when he toppled into the water, his name would be forgotten and his fate unknown.

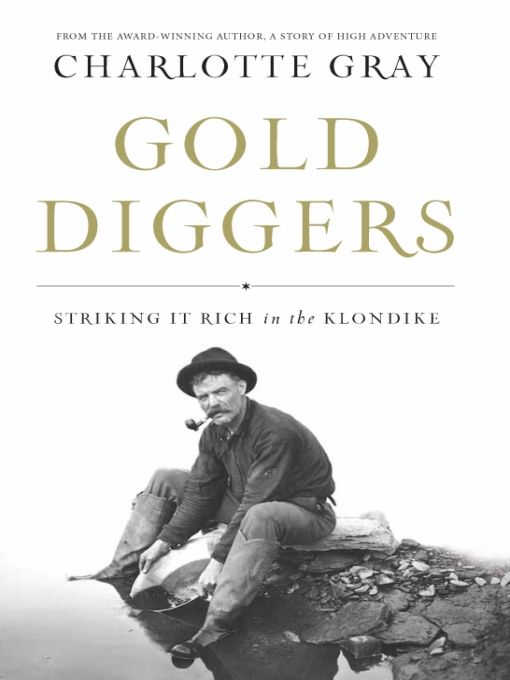

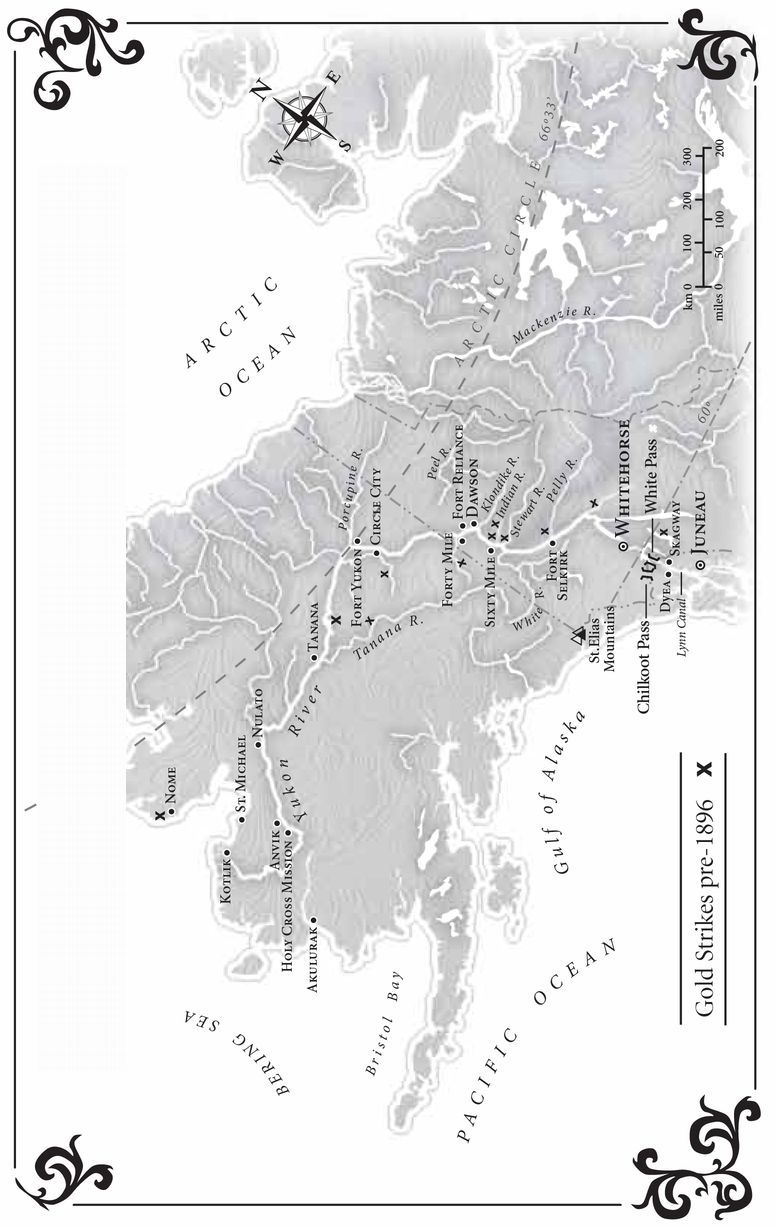

Yet 110 years ago, stampeders streamed north in their tens of thousands in one of the great quests of the nineteenth century. Primarily from the United States but also from Canada, Britain, Australia, Sweden, France, Japan, Italy, and dozens of other countries, they undertook a brutal journey toward the Arctic. They were gamblers and dreamers: the Gold Rush was the chance to reinvent themselvesto escape the claustrophobia of cramped lives, and to share the adrenaline rush of mother lode fantasies and frontier adventure. In an earlier era, similar urges had impelled Europeans to set sail across uncharted oceans. In a later era, the same appetite for speculation persuaded investors to embrace the promise of dot-com stocks.

Different motives impelled me north. My river trip was the culmination of a three-month sojourn in the Yukon. I had hankered to spend time in the immense and almost impenetrable North American wilderness that stretches from the sixtieth parallel to the North Pole, and which freezes into an icy solitude for more than half the year. Moreover, I have three sons, who love to pit themselves against white water, steep mountains, and jagged rock faces. They revel in perilous adventures that fill me with terror of the unknown. They return from such trips exhilarated by their own stamina and courage, humbled by the power of raw nature, and at peace with themselves. I sought a glimpse of their elation.

Most of all, I wanted to see the Yukon with my own eyes. By now I had read dozens of books by survivors of the collective get-rich-quick madness of the 1890s. When I caught sight of the Moosehide Slide, above the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon rivers, I knew the surge of relief and excitement recorded by so many of the men and women who stampeded into the Far North toward the Klondike gold fields. Like me, most of those people had no idea what the terrain was like, no backwoods skills, and only the haziest notion of how to pan for gold.

I was particularly curious about a handful of obsessive, reckless individuals within that torrent of humanity that flowed north. I had heard their voices in memoirs, handwritten letters, or stories. Now I wanted to see and feel for myself what they had seen and felt, to help me understand why they faced such hazards. Why did they hurl themselves so far beyond the horizons rim?

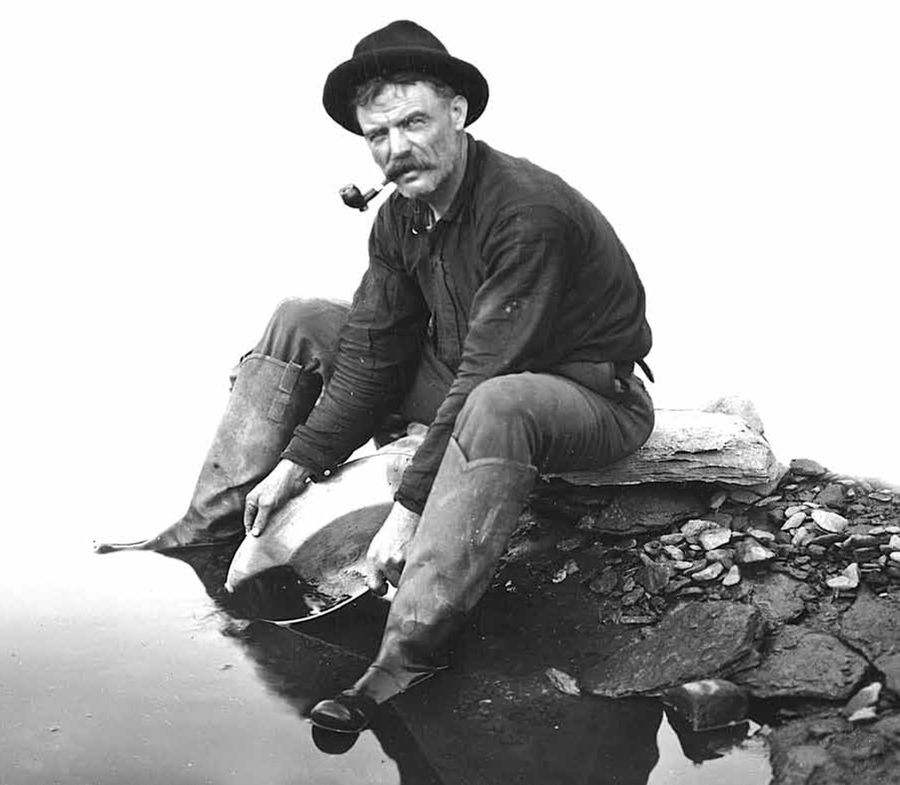

This is the true story, taken from their own words, of six people whose paths crossed during the Gold Rush drama. Had they not made that journey, they would never have met. Woven together, their accounts show how a community develops and how history is built from the ground up. Individual stories have a psychological depth too often missing from the grand narratives of the past, where crowds are faceless and personal motives irrelevant. My six Klondikers were the selfless Jesuit Father William Judge; Belinda Mulrooney, the feisty and ruthless entrepreneur; Jack London, a tough youngster desperate to make his mark on the world; the imperious and imperial Flora Shaw, special correspondent for the Times of London; Superintendent Sam Steele of the Mounties, the barrel-chested lion of the North; and the engaging prospector Bill Haskell. Each of them sought and found richesalthough not always the yellow metal itself. Bill Haskell was the first of the six to make that arduous journey. If it werent for men like Bill, with his incredible tenacity and hunger for adventure, the Klondike Gold Rush might never have happened.

PART 1 : COLOR AND CHAOS

CHAPTER 1

Arctic Secrets, June 1896

THE WIDE RIVER SWEPT the little boat along in its silty current. All the two men had to do was steer clear of hazardsshifting gravel bars, uprooted trees, ice cakes. A thick branch jutting out from the bank could easily catch and swamp their homemade craft. But Bill Haskell couldnt resist glancing up from time to time.

Mile after mile of wildest grandeur glided by like a continuous panorama, he recalled later. It was early June now, and the days were long. Light lingered in the northern sky until after midnight. Sheer cliffs glowed yellow in the midday sunshine or deep purple in the evening shadow. Hillsides were covered in dark spruce forests or slender white birches. Snow still capped the distant mountains.

But Bill and his partner, Joe Meeker, hadnt seen a human habitation for days, and they were intimidated by the landscapes vastness. The beauty was suffused with menace. The hiss of the rivers sediment scraping along the side of the boat, and the harsh croaks of ravens, emphasized the eerie silence rather than broke it. Occasionally, a great bull moose would appear at the waters edge and stare at them. When they pulled their craft onto the bank, they found fresh bear scat and the bleached bones of animals torn to pieces by wolves. At night, wolf howls prickled the hair on the back of Bills neck. When a sudden shower fell, the raindrops were hard, cold pellets of moisture, a stinging reminder that summer here was brief.