William Gibson - Distrust That Particular Flavor

Here you can read online William Gibson - Distrust That Particular Flavor full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: ePubLibre, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

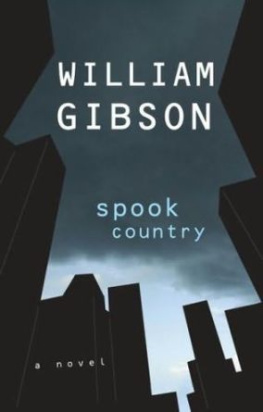

- Book:Distrust That Particular Flavor

- Author:

- Publisher:ePubLibre

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Distrust That Particular Flavor: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Distrust That Particular Flavor" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Distrust That Particular Flavor — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Distrust That Particular Flavor" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE BOY CROUCHES beside a fence in Virginia, listening to Chubby Checker on the Rocket Radio. The fence is iron, very old, unpainted, its uprights shaved down by rain and the steady turning of seasons. The Rocket Radio is red plastic, fastened to the fence with an alligator clip. Chubby Checker sings into the boys ear through a plastic plug. The wires that connect the plug and the clip to the Rocket Radio are the color his model kits call flesh. The Rocket Radio is something he can hide in his palm. His mother says the Rocket Radio is a crystal radio: She says she remembers boys building them before you could buy them, to catch the signals spilling out of the sky.

The Rocket Radio requires no battery at all. Uses a quarter mile of neighbors rusting fence for an antenna.

Chubby Checker says do the twist.

The boy with the Rocket Radio reads a lot of science fictionvery little of which will help to prepare him for the coming realities of the Net.

He doesnt even know that Chubby Checker and the Rocket Radio are part of the Net.

* * *

ONCE PERFECTED, communication technologies rarely die out entirely; rather, they shrink to fit particular niches in the global info-structure. Crystal radios have been proposed as a means of conveying optimal seed-planting times to isolated agrarian tribes. The mimeograph, one of many recent dinosaurs of the urban office place, still shines with undiminished samizdat potential in the centurys backwaters, the late-Victorian answer to desktop publishing. Banks in uncounted third-world villages still crank the days totals on black Burroughs adding machines, spooling out yards of faint indigo figures on long, oddly festive curls of paper, while the Soviet Union, not yet sold on throwaway new-tech fun, has become the last reliable source of vacuum tubes. The eight-tracktape format survives in the truck stops of the Deep South, as a medium for country music and spoken-word pornography.

The Street finds its own uses for thingsuses the manufacturers never imagined. The microcassette recorder, originally intended for on-the-jump executive dictation, becomes the revolutionary medium of magnitizdat, allowing the covert spread of suppressed political speeches in Poland and China. The beeper and the cellular telephone become tools in an increasingly competitive market in illicit drugs. Other technological artifacts unexpectedly become means of communication, either through opportunity or necessity. The aerosol can gives birth to the urban graffiti matrix. Soviet rockers press homemade flexi-discs out of used chest X rays.

* * *

THE KID with the Rocket Radio gets older. One day he discovers sixty feet of weirdly skinny magnetic tape snarled in roadside Ontario brush. This is toward the end of the Eight-Track Era. He deduces the existence of the new and exotic cassette format: this semi-alien substance, jettisoned in frustration from the smooth hull of some hurtling Vette, settling like new-tech angel hair.

I BELONG to a generation of Americans who dimly recall the world prior to television. Many of us, I suspect, feel vaguely ashamed about this, as though the world before television was not quite, well, the world. The world before television equates with the world before the Netthe mass culture and the mechanisms of Information. And we are of the Net; to recall another mode of being is to admit to having once been something other than human.

The Net, in our lifetime, has propagated itself with viral rapidity, and continues to do so.

In Japan, where so many of the Nets components are developed and manufactured, this frantic evolution of form has been embraced with unequaled enthusiasm. Akihabara, Tokyos vast retail electronics market, vibrates with a constant hum of biz in a city where antiquated three-year-old Trinitrons regularly find their way into landfill. But even in Tokyo one finds a reassuring degree of Net-induced transitional anxiety, as I learned when I met Katsuhiro Otomo, creator of Akira, a vastly popular multivolume graphic novel. Neither of us spoke the others language: Our mutual publisher had supplied a translator, and our conversation was relentlessly documented. But Otomo and I were still able to share a moment of universal techno-angst.

HIS LIVING ROOM was dominated by a vast matte-black media node that would put most Hollywood producers to shame. He pointed to an eight-inch stack of remote-control devices.

I dont know how to use them, he said, but my children do.

I dont know how to use mine, either.

Otomo laughed.

Today, Otomos collection of remotes is probably part of some artfully bulldozed gomi plain, landfill for Neo-Tokyo. Gomi: Japanese for garbage, a lot of which consists of outmoded consumer electronicssuch as those recently redundant remotes. Wisely assuming a constant source, the Japanese build themselves more island out of it.

The sexiness of newness, and how it wears thin. The metaphysics of consumer desire, in these final years of the twentieth century

Two years ago I was finally shamed into acquiring a decent audio system. A friend had turned up in the new guise of high-end-audio importer, and my old system, so to speak, caused him actual pain. He offered to go wholesale on a total package, provided I let him select the bits and pieces.

I did.

It sounds fine.

But Im not sure I really enjoy the music any more than I did before, on certifiably low-fi junk. The music, when its really there, is just there. You can hear it coming out of the dented speaker grille of a Datsun B210 with holes in the floor. Sometimes thats the best way to hear it.

I knew a man once whose teen years had been L.A., jazz, the Forties. He spoke of afternoons hed spent, utterly transported, playing 78-rpm recordings, worn down white with repeated applications of a sharp steel stylus. That is, the shellac that carried the grooves on these originally black records was plain gone: What he must have been listening to could only have been the faintest approximations of the original sound. (Rationing affected steel phonograph needles, he told me, desperate hipsters resorted to the spikes of the larger cactuses.)

That man heard that music.

I first heard the Rolling Stones on a battery-powered, basketball-shaped, pigskin-covered miniature phonograph of French manufacturea piece of low tech as radical in its day as it is now obscure. Radical in that it enabled the teenage owner to transport LP records and the intoxicant of choice to suitably private locationsthe boonies.

This constituted an entirely new way to listen to the music of choice. Choice being the key word. The revolutionary potential of the D-cell record player wasnt substantially bettered until the advent of the Walkman, which allows us to integrate the music of choice with virtually any landscape.

The Walkman changed the way we understand cities.

I first heard Joy Division on a Walkman, and I remain unable to separate the experience of the musics bleak majesty from the first heady discovery of the pleasures of musically encapsulated fast-forward urban motion.

In the Seventies, the Net writhed with growth. Gaps began to close. A paradox became increasingly evident: While artists needed the Net in order to reach a mass audience, it seemed to be the gaps through which the best art emerged, at least initially.

I am, by trade, a science-fiction writer. That is, the fiction Ive written so far has arrived at the point of consumption via a marketing mechanism called science fiction. During the past twenty years the Net has closed around mass-market publishingand science fictionas smoothly as it closed around the music industry and everything else.

As a science-fiction writer, Im sometimes asked whether or not I think the Net is a good thing. Thats like being asked if being human is a good thing. As for being a human being a good thing or not, I cant saythis has been referred to as the Postmodern Condition.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Distrust That Particular Flavor»

Look at similar books to Distrust That Particular Flavor. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Distrust That Particular Flavor and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.