Terrace Books, a trade imprint of the University of Wisconsin Press, takes its name from the Memorial Union Terrace, located at the University of WisconsinMadison. Since its inception in 1907, the Wisconsin Union has provided a venue for students, faculty, staff, and alumni to debate art, music, politics, and the issues of the day. It is a place where theater, music, drama, literature, dance, outdoor activities, and major speakers are made available to the campus and the community. To learn more about the Union, visit www.union.wisc.edu.

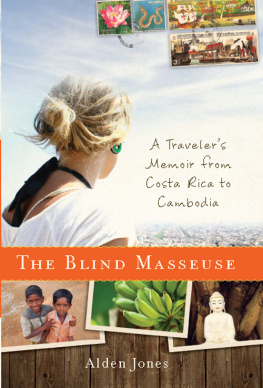

T HE B LIND M ASSEUSE

ALDEN JONES

TERRACE BOOKS

A trade imprint of the University of Wisconsin Press

Terrace Books

A trade imprint of the University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 2013 by Alden Jones

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jones, Alden.

The blind masseuse: a travelers memoir from Costa Rica to Cambodia / Alden Jones.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-299-29570-7 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-29573-8 (e-book)

1. Jones, AldenTravel. 2. Travel. 3. Voyages and travels. I. Title.

G465.J647 2013

910.4dc23

2013014543

Lard Is Good for You originally appeared in Coffee Journal, December 1999, and was reprinted in Best American Travel Writing 2000. The Answer Was No originally appeared in Gulf Coast, Summer/Fall 2004, and was named Notable Travel Writing in Best American Travel Writing 2005. This Is Not a Cruise originally appeared in The Smart Set, Fall 2007. The Burmese Dreams Series originally appeared in Post Road, December 2010, and was named Notable Travel Writing in Best American Travel Writing 2011.

This is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed, and in some cases chronology has been sparingly condensed or rearranged for the benefit of narrative clarity.

For

MY PARENTS

and for

KATE

Contents

The Blind Masseuse

INTRODUCTION

The Charm of the Unfamiliar

While walking home to Rafaels house, I bumped into a cow. It wasnt too unusual to encounter a cow in a place like La Victoria, Costa Rica; I was in farmland, after all. But because it was pitch black, I didnt understand at first what had happened to me. My belly made contact with something firm, but fleshy, and I bounced lightly backward and stopped. When I aimed my vision at the invisible obstruction, I began to make out the outline of the cows back and ears and the white spots on her hide.

The cow had wandered out of a nearby enclosure and stopped to rest, or perhaps sleep, in the middle of the dirt road I took home every day. I had been out drinking Imperial beers with my friend Lisa in Turrialba. Id taken a cab home because buses stopped running at 7:10. It was now around nine, very late. Between the few stray streetlights and the moonlight I could usually make my way to the end of town where I lived with Rafael and his family. Sometimes I tripped on stray rocks or stumbled over roots, but a cow had never been an obstacle on this path, not even in daytime.

The cow was undisturbed. I was calm but I realized I was holding my breath. It had been a shock, being sent backward like that.

I pat-patted the cow in apology, made my way around her, and continued down the path.

Inside the few concrete square houses at the end of town, everyone was fast asleep. The people here were farmers and the children of farmers. I was the only one in town out drinking beers past seven. The sensation of warm bellies meeting remained, and I found myself returning to the moment of bewilderment, the space between being halted in my path and comprehending the presence of the cow. For a few seconds I was in a world that made no sense. If Carolina, the girl who lived in the house I now approached, had made her way down the dark path, she would have likely seen the cow coming. But for me, a girl born in Manhattan and raised in New Jersey who had been in rural Costa Rica only a few months, it was so outside of my experience that it simply did not compute.

The bewilderment lingeredI was savoring it, in factand left me with a buzzing feeling in my head. It was a tiny thing, a tiny moment. But I was completely in my body and my life in a way that felt rare and very good.

That buzzing in my head was the feeling of exoticism. It was the delight of having something bizarre or unfamiliar happen, and knowing that, from the point of view of anyone inside those concrete houses I passed, it was absolutely unremarkable. It was bizarre only because of cultural context. It was the split in my own perspective of the world. These moments of absurdity made me feel so alive I almost felt high.

Many travelers seek out this high. We seek out what is different from what we behold in our daily lives, whether it is language, fashion, standards of behavior, architecture, climate, or animal species, because beholding what is different has the quality of being unreal. If our brains resist the realness of something, but this thing is before our eyes, were accompanied by little sparks of excitement just by moving through the world. While tourists spend their time away from home seeking out the comforts of home, travelers riskeven cultivate discomfort, because what they want is the thrill of a new perspective. What is it like to reside in a culture where women must cover their arms and legs and still be subject to harassment? What does Nicaraguan mondongo taste like? How much guilt can you handle when you compare your comfortable American life to the lives of Burmese terrorized, every day, by their own government?

For most of my life, I have traveled seeking answers to hard questions. Ive traveled to understand the human condition in its relativity. Ive traveled to learn other languages and to do my best to understand people across cultures. Ive also traveled for the high.

Travel was always a part of our familys life, but it was not something we considered glamorous. My father, a golf course architect, traveled all over the United States and internationally, but he was dedicated to being a present parent and cultivated a strong domestic business. As a family, during my childhood, we traveled along the East Coast, visiting my mothers family in North Carolina and my fathers in Florida. The places we traveled were too familiar to be exotic.

Exoticism, by definition, is the charm of the unfamiliar. Europe first snagged my attention as the distant but attainable Other when I was fourteen. The difference between the United States and Europe was embodied, I thought, in the design of my high school history textbooks: my U.S. history text, crammed with tales of musket battles and Puritan restraint, was housed in a bland beige cover and decorated with the muted foliage of a Hudson River School painting; my European history text was boldly red and showcased a royal family clad in finery and encircled by tapestries, silver, burning candles, and oil paintings. The deeper into the red text I studied, the more entranced I was by open feuds between royal families, the zeal required to risk ones life laboring on a cathedral, and such bad behavior as blatant looting in the name of religious crusades. I was bright-eyed for the city of Paris and the islands of Italy and Greece. Exoticism often beginsGustave Flaubert could tell you thisin books. As a teenager I read Sartre for fun (though I did not understand him even in English) and fantasized about the day I would read him in French. I traced the Greek alphabet from the