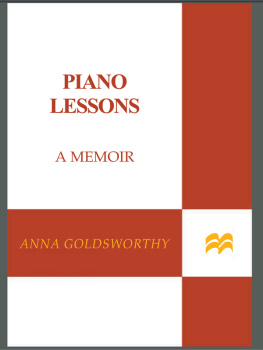

For Sarah

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously.

First published in 2017

Copyright Tony Jones 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

Print ISBN 978 1 76029 500 4

eBook ISBN 978 1 76063 906 8

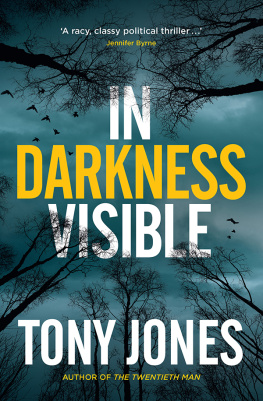

Cover design: Luke Causby/Blue Cork

Cover images: Mark Owen / Arcangel (front);

AdobeStock (back); Tony Jones (Ben Dearnley)

Contents

Saturday, 16 September 1972

The figures on the platform blurred as the train gathered speed through Central Station.

He saw women in spring dresses and men in short sleeves. Sea Eagles fans in maroon and white, and others in the Roosters tricolours heading out early to the rugby league grand final. A platform guard, a Chinaman in a white shirt, mothers and children.

Mothers and children! A girls face flashed by. No matter how many times he had steeled himself against this thought, these people were real.

Two boys skylarked in the open doorway of the red rattler, holding on to the poles and leaning out of the carriage as it rushed towards the tunnel. They laughed as the wind lifted their hair. Their mother yelled at them and at the last moment they ducked back inside before the tunnel closed around them.

Upright columns loomed and passed one after the otherwhoosh, whoosh, whooshand he blinked at the assault on his eyes, forced to look away. It was an odd, nostalgic discomfort: he remembered looking through these windows as a child on his way to the city, the warm bodies of his father and mother pressed close on either side of him.

The train rattled and bucked and he tightened his grip on the two shopping bags, cradling them between his legs against the movement. He glanced again at his old wristwatch. 10.50 am.

He looked at the other passengers in the carriage. Had they noticed anything about his movements, something furtive? No, no one was watching him.

Several of the men on the other side of the carriage were reading newspapers; the woman directly opposite was clasping a handbag on her lap, avoiding eye contact, as if in a doctors reception, waiting for some shameful procedure; a boy and his girlfriend whispered to each other, heads together. They were all preoccupied, enclosed in invisible fields of disregard.

Save the mother, who followed her boys every move, ready to intervene to prevent catastrophe. She hadnt noticed the man with the shopping bags sitting next to her, though he was surely her worst nightmare. He whose senses were so completely engaged and raw andyes, he could say thisprimitive. He registered that, despite her alertness to the obvious dangers to her children, her instincts were dulled. She saw the cliffs edge but not the lurking predator.

In the close confines of the tunnel, the racket through the open doors and windows drowned out all other sound. As the noise peaked, the carriage lights suddenly flickered off. The ensuing blackout was accompanied by shrieks and howls as the straining mechanics and couplings, the metal-on-metal scrapings and the electrical contacts produced the sounds of a torture chamber while the decrepit red rattler barrelled through the darkness. If all the passengers screamed at once they would barely be heard above the din. He truly felt like screaming, actually, but he suppressed the urge as though holding back a sneeze.

When the lights came back on he glanced again at his watch. He told himself not to but it was irresistible. Its imperfect mechanism was like a heart beating too fast. The damn thing was gaining time, moving ahead of itself, ahead of the schedule. He sensed an acceleration of the coming events and took out a handkerchief, wiping sweat from his face. He shouldnt do that either, but the faulty watch was making it all worse.

There was a long squeal of brakes, the noise confined and then cavernous as the train thrust out of the tunnel and into the urinous light of Town Hall Station. Green tiles and dark bodies. A muffled station announcement as people rose in the carriage around him. So did he, jerkily in the sudden deceleration.

He had a shopping bag in each hand and stumbled against the mother, who was now beseeching her sons to wait. The boys ignored her, springing off the still-moving carriage and letting the momentum carry them through the crowd and straight on to the escalator. The mother caught his eye, and he saw a panicked look before she bustled her way to the door.

He moved in her wake through the parting crowd, which opened as if in response to the mothers distress. He used her momentum to drag himself along and on to the escalator, saving time now, gaining on his watch. The womans thick hips rolled in a steady rhythm as she stomped up the moving stairs.

The boys were waiting at the top and she rounded on them, grabbing the younger one by the ear and slapping the older ones cheek. He kept walking, registering a small shock as he passed them. His own mother had never hit him. Shed had a dark mist around her, disappearing before he was the age of either of these boys.

Not now! Put that memory away

He switched the bags to one hand, pulled out his ticket and passed through the barrier before rebalancing his load.

The underground concourse was full of people and he joined the flow before peeling off to the public toilet. Once inside he edged past men facing the stinking urinals and moved along the row of cubicles to the furthest empty one. He locked himself inside, sat on the toilet seat and took a deep breath. The door in front of him was scored with obscene messages and a crudely drawn cock above a phone number. He grimaced, pulled out his handkerchief, wiped his brow again and dried his hands. He held his right hand out on a horizontal plane. Steady, no shakes.

He opened one of the shopping bags, took out the old towel that covered the contents and laid it on his knees. He reached down and gently removed a heavy brown package swathed in tape. Attached to the top, and wired to batteries and detonators, was his most accurate watch. Now he set the timer, put the live bomb back in the shopping bag, and covered it up again. Then he repeated this procedure with the bomb in the second bag.

When he stood up it was too quickly. Dizziness. He sat back down, closed his eyes and took slow, deep breaths.

He visualised the timing devices. He had constructed them himself with utmost care. A perfectionist and highly skilled in this art, he had repeated the procedure of setting the timers in training. But despite all his precautions, his mind turned to Tomislav Lesic. He thought every day about Lesic, whose legs had been blown off when a bomb he was carrying exploded in a quiet street in Petersham.

Lesic had been an amateur and a fool. His own method was infallible.

Next page