CYBERPUNK

Stories of Hardware, Software, Wetware, Evolution and Revolution

EDITED BY VICTORIA BLAKE

Copyright 2013 Underland Press. All Rights Reserved.

Requests for permission to reproduce material

from this work should be sent to:

Rights and Permissions

Cover design by Claudia Nobel

Text Design by Heidi Whitcomb

ISBN: 978-1-9371-6309-9

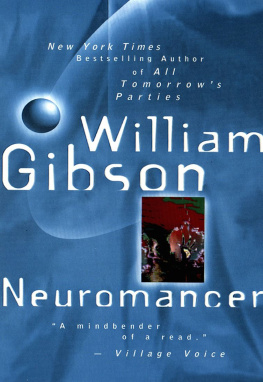

Johnny Mnemonic, by William Gibson, first appeared in Omni, 1981, copyright Omni Publications International 1981, used by permission of the author

Mozart in Mirrorshades, by Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner, first appeared in Omni, 1985, copyright Omni Publications International 1985, used by permission of the authors

Interview with the Crab, by Jonathan Lethem, first appeared in Bread #1, 2005, printed in Men and Cartoons, copyright 2004, 2012 Jonathan Lethem

El Pepenador, by Benjamin Parzybok, collection original, copyright 2012 Benjamin Parzybok

Down and Out in the Year 2000, by Kim Stanley Robinson, first appeared in Isaac Asimovs Science Fiction, April 1986, copyright 1986 Kim Stanley Robinson

Rock On, by Pat Cadigan, first appeared in Light Years and Dark, copyright 1984 Pat Cadigan

Getting to Know You, by David Marusek, first appeared in Future Histories, 1997, copyright 1997 David Marusek

User-Centric, by Bruce Sterling, first appeared in Designfax, 1999, copyright 1999 Bruce Sterling

The Blog at the End of the World, by Paul Tremblay, first appeared in Chizine, 2008, copyright 2008 Paul Tremblay

Memories of Moments, Bright as Falling Stars, by Cat Rambo, first appeared in Talebones, winter 2006/2007, copyright 2007, 2012 Cat Rambo

Blue Clay Blues, by Gwyneth Jones, Interzone, 1992, copyright 1992 Gwyenth Jones

The Lost Technique of Blackmail, by Mark Teppo, Electric Velocipede #19, Fall 2009, copyright 2009 by Mark Teppo

Soldier, Sailor, by Lewis Shiner, first appeared in Nine Hard Questions About the Nature of the Universe, 1990, copyright 1990 Lewis Shiner

Mr. Boy, by James Patrick Kelly, first appeared in Asimovs Science Fiction, June 1990, copyright 1990 James Patrick Kelly

The Jack Kerouac Disembodied School of Poetics, by Rudy Rucker, first appeared in New Blood, July 1982, copyright 2012 Rudy Rucker

Wolves of the Plateau, by John Shirley, first appeared in Heatseeker, copyright 1989, 2012 by John Shirley

The Nostalgist, by Daniel H. Wilson, first appeared on Tor.com, 2009, copyright 2009 Daniel H. Wilson

Life in the Anthropocene, by Paul Di Filippo, first appeared in The Mammoth Book of Apocalypse SF, copyright 2010 Paul Di Filippo

When Sysadmins Ruled the Earth, by Cory Doctorow, first appeared in Baens Universe, 2006, copyright 2006 CorDoc-Co, Ltd. Some rights reserved under a creative commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Victoria Blake |

William Gibson |

Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner |

Jonathan Lethem |

Benjamin Parzybok |

Kim Stanley Robinson |

David Marusek |

Bruce Sterling |

Paul Tremblay |

Cat Rambo |

Pat Cadigan |

Gwyneth Jones |

Mark Teppo |

Lewis Shiner |

Rudy Rucker |

James Patrick Kelly |

John Shirley |

Daniel H. Wilson |

Paul Di Filippo |

Cory Doctorow |

By Victoria Blake

As American SF lies in a reptilian torpor, its small, squishy cousin, Fantasy, creeps gecko-like across the bookstands, Bruce Sterling wrote in the first issue of Cheap Truth, a one-page, double-sided bright coal of a fan-zine first published in 1983. Dreaming of dragon-hood, Fantasy has puffed itself up with air like a Mojave chuckwalla. SFs collapse ha[s] formed a vacuum that forces Fantasy into a painful and explosive bloat... Short stories, crippled with the bends, expand into whole hideous trilogies as hollow as nickel gumballs.

These were fighting words, aimed directly at the bulls-eye of publishers, editors, critics, authors, and readers in the smokestack publishing-industrial complex. There was, Sterling wrote in Cheap Truth issue five, a crying need to re-think, re-tool, and adapt to the modern era. SF has one critical advantage: it is still a pop industry that is close to its audience. It is not yet wheezing in the iron lung of English departments or begging for government Medicare through arts grants.... SF has always preached the inevitability of change. Physician, heal thyself.

The physician, in this case, was the collection of early 80s writers that Cheap Truth showcased as carriers of the flameLewis Shiner, Rudy Rucker, William Gibson, et aland the challenge was to find a new voice for a new kind of reader in a new kind of world. This years Nebula Ballot looked like a list of stuff that Mom and Dad said it was okay to read, a pseudonymous Lewis Shiner wrote in Cheap Truth. I mean, this is the kind of writing that Mom and Dad grew up on, full of Gollys and blushes and grins. And arent those dolphins cute?... Theyd rather hear that somebody muttered an oath or came out with some made-up word like Ifni! than be told that they really said shit or shove it up your ass, motherfucker.

Nobody had ever read anything like what the cyberpunks were writingstories and novels that were the bastard child of science fiction, with a common-man perspective, a love of tech and drugs, and an affinity for street culture. That most cyberpunk was written by white males didnt seem to ruffle any feathers. Cyberpunk was new, it was vital, it was irreverent. Most importantly, cyberpunk rocked.

When Sterling and his gang of pranksters shuttered Cheap Truth in 1985, a mere eighteen issues after launch, he declared that the movement was over, it had become too big, and that much of the original freedom was lost. People know who I am, he wrote, and they get all hot and bothered by personalities, instead of ideas and issues. CT can no longer claim the honesty of complete desperation. That first fine flower of red-hot hysteria is simply gone. In other words, The Movement had been changed by its acceptance into the smokestack machine. (Cheap Truth had been mentioned in an issue of Rolling Stone, evidence of it being swallowed whole.) When, in 1986, Sterling published Mirrorshades, the first and some say only true cyberpunk anthology, the movement was consolidated into a particular table of contents, a closed club whose membership was limited to the original cyberpunk writers. In 1991, Lewis Shiner renounced cyberpunk in a New York Times op-ed. When Time ran a cover story about cyberpunks, the cyberpunks themselves were outraged. Counter culture had been embraced by culture. I hereby declare the revolution over, Sterling wrote in the final issue of Cheap Truth. Long live the provisional government.

Thirty years later, cyberpunk is both very much dead and very much alive. It is dead in the sense that the Reagan years are over, the Cold War is done, straight video has been replaced by CGI, and the achievement of the Xerox machine, once the very pinnacle of technological advancement available to the masses, is being outdone by 3-D printers. But it is very much alive in that cyberpunk was never really about a specific technology or a specific moment in time. It was, and it is, an aesthetic position as much as a collection of themes, an attitude toward mass culture and pop culture, an identity, a way of living, breathing, and grokking our weird and wired world.

Next page