Copyright 2006 by Lyanda Lynn Haupt

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

www.twitter.com/littlebrown

First eBook Edition: September 2009

The excerpt from 1 died from Beauty on pages 252-253 is reprinted by permission of the publishers and the Trustees of Amherst College from The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition, Ralph W. Franklin, ed., Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright 1998 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright 1951, 1955, 1979 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

The images that appear on pages iii, 9 61, 83, 107, 116, and 181 are courtesy of the Ewell Sale Stewart Library, The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

ISBN: 978-0-316-08296-9

Rare Encounters with Ordinary Birds

For Tom

hiker

biker

juggler

recycler

and love of my life

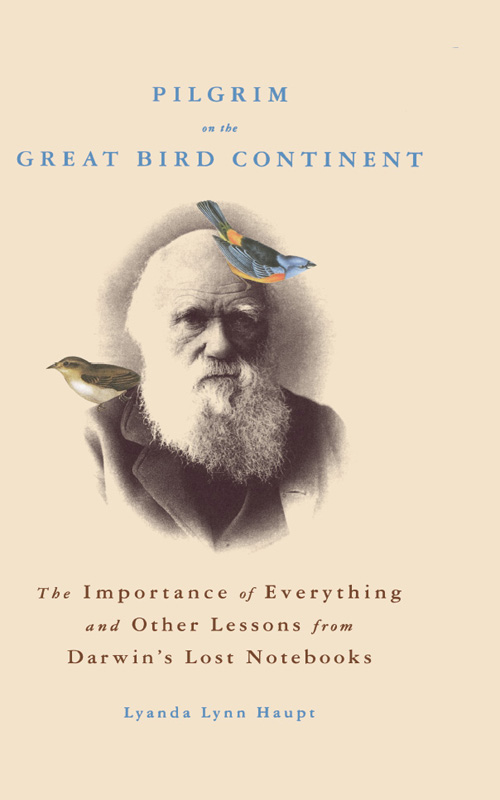

C harles Darwins work has been plumbed for details of natural selection theory and its relevance for modern science and philosophy. His life has been told in biographies that inspire admiration for his experience, his eccentricities, his intelligence, his theories. Pilgrim on the Great Bird Continent approaches Darwin on a much more personal level. Here, I want to consider Darwin not just as a bearer of natural selection theory but as a human who both understood and related to the natural world in such a way that this theory became possible. For as a young man embarking on his journey aboard the Beagle, he possessed no such vision. He developed it through work, study, persistence, and a measure of earthen grace a grace that even Darwin, striving to be wholly scientific, admitted.

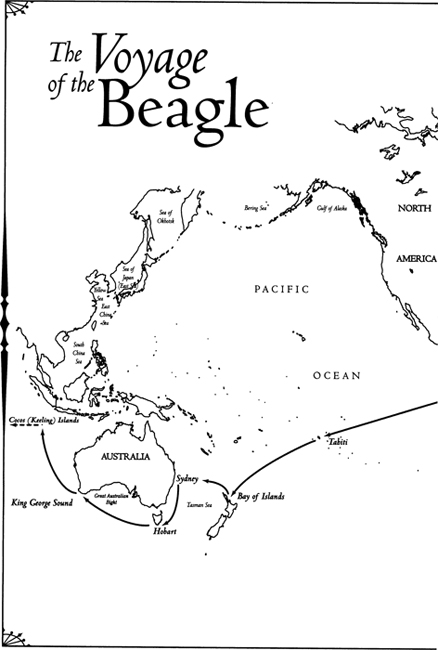

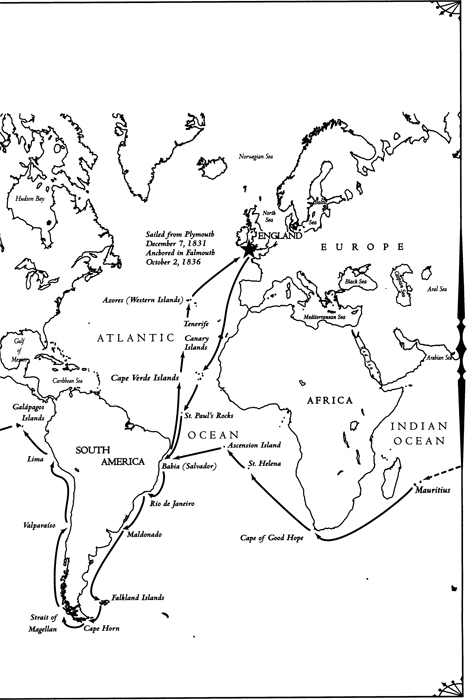

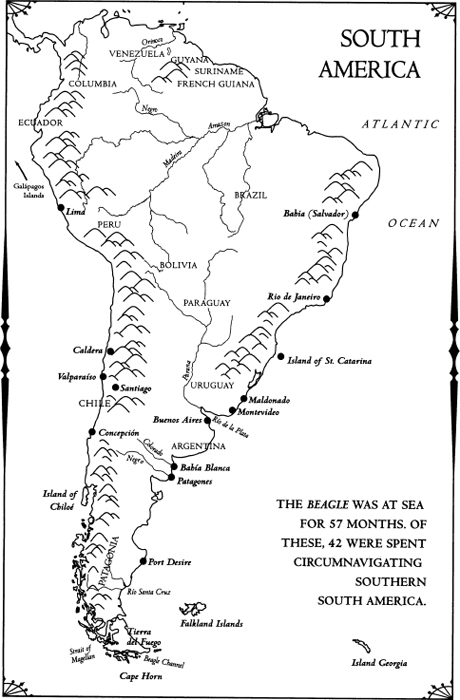

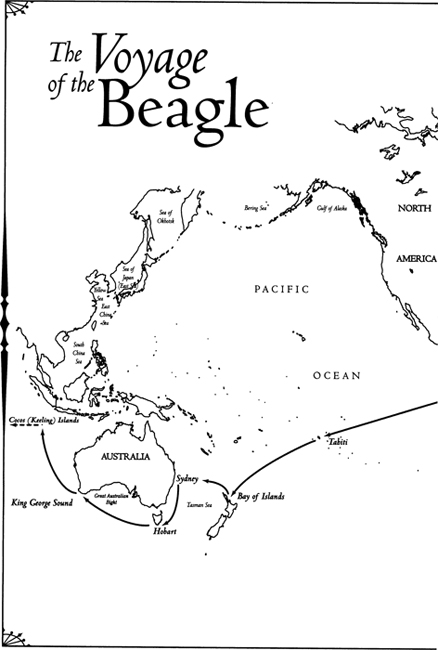

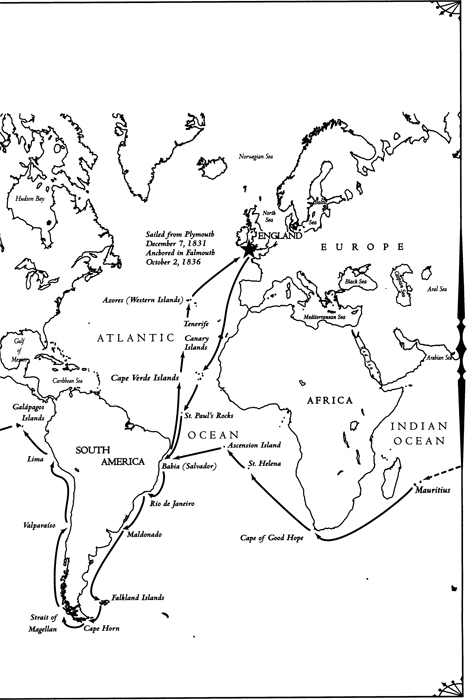

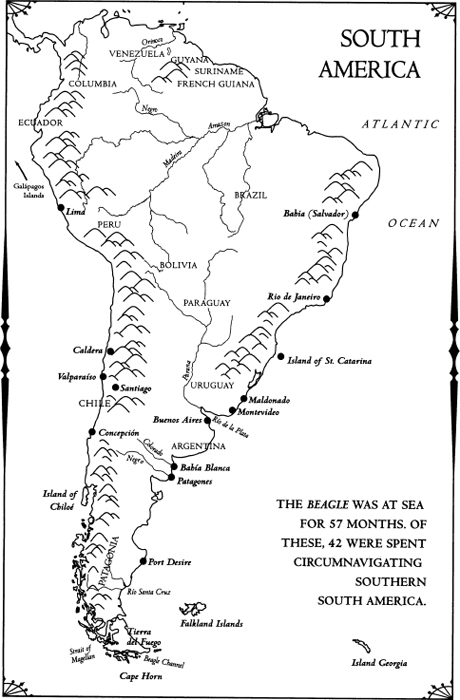

When Darwin stepped onto the HMS Beagle in 1831, he was only twenty-two years old. He had no official position on this naval vessel in service to the Crown but was invited along as a gentleman companion to the fastidious, melancholy, equally young Captain FitzRoy, and to work privately as a naturalist. Darwins father paid his expenses. The voyage, originally scheduled to span two years, dragged on for nearly five. The Beagles ostensible mission was to use new marine chronometers to accurately chart the perimeter of southern South America and to resolve discrepancies on existing charts and maps. But the emerging business of colonialism drove other dimensions of such voyages. The British would use the information obtained by this and other vessels to determine naval and commercial plans, plot the exploitation of resources such as gold, diamonds, and guano (a valuable fertilizer in nineteenth-century England), and establish Anglican missions. During the Beagles many coastal moorings, Darwin stayed ashore and took overland journeys as often as possible to escape his perpetual seasickness and to study natural history, which he pursued with increasing depth and intensity.

Darwin had been attracted to the study of natural history since childhood and had always maintained a rather expansive view of the importance of his own observations. When he was not hiding under the dining room table reading Robinson Crusoe for inspiration, he was traipsing the grounds of the family estate, making notes about the comings and goings of the pheasants, the state of various swallows nests, the colors of butterflies, the shapes of clouds. All these he would solemnly report to his father and sisters in the evening (Darwins mother died when he was eight), not bothering to differentiate between the common blackbirds he actually saw and the rare birds whose presence he invented.

Charles intended to follow in his fathers footsteps by studying medicine at Edinburgh University, but he was altogether repulsed by the surgical theater. The screams he witnessed during the amputation of a childs leg without anesthesia tormented him through the whole of his life. He ran from Edinburgh with his hands over his ears and knots in his stomach. Dr. Darwin was not impressed, but he helped his son to fashion an alternative career; Charles would be a clergyman and take up his studies at Cambridge.

It was here that Darwin found naturalist mentors, and he ingratiated himself so thoroughly with the brilliant botanist John Henslow that his fellow students began to refer to him teasingly as the man who walks with Henslow. He remained a desultory student as far as his clerical preparations were concerned, but he attended natural history lectures, helped Henslow to organize his collections, joined field excursions, and in line with the Victorian craze for natural history curios and cabinets zealously collected beetles.

About this time, Darwin happened upon some family financial documents that confirmed what he had previously suspected: He was rich, or at least rich enough. As a member of the landed gentry, he should hold some sort of position (and clergyman a rather amorphous and symbolic post in Victorian England would be perfect), but he would never have to engage in the tasteless work of earning a wage. Pleased, Darwin decided to indulge his longing for travel before settling into his comfortable life happily collecting beetles into his old age while raising dogs and a few children on the side. As he dreamed over the travel memoir of his idol Alexander von Humboldt, Darwin threw himself into planning a trip to Tenerife, dragged unwitting friends into the plan, and was trying to think up a tactful, persuasive way to ask his father to fund it. But then the offer from Captain FitzRoy came, and Darwin joined the Beagle.

Stepping aboard the Beagle, Darwin appeared to be nothing out of the ordinary. He was interested in natural history and clearly displayed some aptitude. His teachers liked and recommended him. He was delighted to have the opportunity. And thats about it. In his letter of recommendation for the Beagle post, Professor Henslow wrote of Darwin that he was not a finished naturalist. He was a beginner, still relying heavily on books and teachers for information; he was not finished, but for this little post he would do nicely. Many biographers have written obliquely of Darwins transformation he left London unfinished, he studied all manner of life on earth intensely for five years, he had many adventures and brilliant thoughts, and he came back finished, a naturalist with his life and work well in hand. In his introduction to a recent edition of Darwins Beagle journal, Steve Jones writes, Darwin left England as an enthusiastic amateur, but returned as a professional scientist.