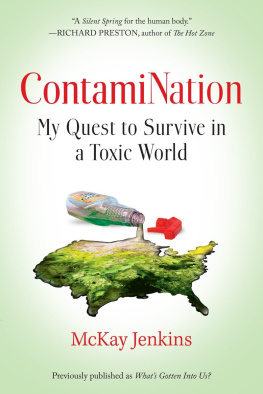

ALSO BY McKAY JENKINS

Bloody Falls of the Coppermine

The Last Ridge

The White Death

The Peter Matthiessen Reader (editor)

The South in Black and White

Copyright 2011 by McKay Jenkins

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered

trademarks of Random House, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Jenkins, McKay

Whats gotten into us?: staying healthy in a

toxic world / McKay Jenkins.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60497-6

1. Environmental healthUnited States.

2. Environmental toxicologyUnited States.

I. Title.

RA566.3.J46 2011 362.19698dc22 2010026778

www.atrandom.com

Jacket design: Anna Bauer

Jacket photograph: Jeffrey Coolidge/Getty Images

v3.1

FOR KATHERINE, STEEDMAN, AND ANNALISA

WITH LOVE, DEVOTION, AND GRATITUDE

O n a crisp fall afternoon a couple of years ago, I went in for a routine two-year checkup with my internist. Everything seemed to be fine: My home life was happy and nurturing. I had never smoked. I ate right, got plenty of rest, and had been a dedicated runner and cyclist my entire adult life. Save for the usual aches and pains, nothing had ever been wrong with my body, and as long as I was smart about it, I figured, Id still be riding my Fausto Coppi racing bike well into my eighties.

My only complaint, I told my doctor, was a faint tightness in my hip that I had felt off and on for two yearsand odd, sharp twinges between my left thigh, knee, and shin that occasionally accompanied it. Sometimes the skin on my leg itched. Sometimes it burned. Sometimes the ligaments in my knee hurt. Id consulted with a dermatologist months before, but had gotten no answers. Were these symptoms related? My internist was perplexed. Perhaps it was an overuse injury, he said, something Id developed from too much running in the woods or riding the rural roads near my home. Like anyone who has tried to stay in shape through their postcollege years, I was familiar with such aches and pains. As the years went by, fewer and fewer were the days when I didnt feel some minor muscle or joint ache after even a light workout. I was getting older, and so was the machinery.

My internist looked me over and agreed that my pains were probably related to exercise, and he suggested I see an orthopedist at a nearby sports medicine clinic. I called and got an appointment that very morning. I walked into the orthopods office ready for a quick diagnosis and a pat on the head. Someone as fit as you can expect to have occasional ligament stress, I expected him to say. Heres the name of a physical therapist. Go get a massage, and check in with me on your seventy-fifth birthday.

This is not what he said.

After hearing my description of the pain, the orthopedist rotated my hip and knee a couple of times. He seemed puzzled. This didnt seem like a joint problem, and in any case the pain in my knee was probably referred pain radiating from my hip. He suggested I get an MRI to help him see a bit more clearly what was going on with my soft tissue.

Okay, I thought: people get MRIs all the time. Especially athletes. Theyd probably just find a slight tear in some connective tissue, Id buy a new pair of running shoes, and away Id go. Worst case? A little minor surgery to fix an abraided tendon. I got an appointment that afternoon, spent forty-five unpleasant minutes inside a clanging metal tube, and went home to wait for the resultswhich, given the routine nature of the exam, I figured would take a few days, or even weeks.

I was standing in my living room when the phone rang just a few hours later. This was an awfully quick turnaround, I thought, looking at the caller ID. These lab techs must be having a pretty light day at the office. But when I picked up the phone and heard the orthopedists voice, I knew even before he spoke that something was amiss.

Hello, Mr. Jenkins, he said, then paused. You have a suspicious mass in your abdomen, he said. Its growing inside your left hip. Here is the number for an oncologist. You need to call him right away.

W hat can you say about such moments? I remember hanging up the phone. I remember looking at my wife, Katherine, and looking at my children putting together a puzzle on the floor in the next room. My son was four, my daughter not yet eighteen months. I fell apart.

Far worse than my fears for myself were my worries about my kids. How would they get by without a father? Trying to protect them from the initial shock of the news, Katherine and I took turns taking our cell phones outside to talk to doctors and loved ones. Standing in the yard, trying to set up a date for a CT scan, I would look through the living room window to see my kids playing together. I imagined the same scene, with me gone. I felt like a ghost.

Katherine and I passed the next three weeks in a kind of silent panic. We spent anxious hours on the Internet, blindly researching what this thing was that was growing between my hip and my belly. This was a very bad idea. We called every doctor we knew.

I held it together enough to keep teaching my classes at the University of Delaware, which is about an hour north of our home in Baltimore. One day, when I returned to my office after a morning class, there was a message on my phone. It was from Katherine. I found an oncologist, she said, but you need to get here fast; hes really busy and has only one opening this week. I ran into my classroom, scrawled Class canceled on the blackboard, and dashed off to my car.

When I got to the hospital, Katherine was already there, waiting in the parking lot. We hugged, and went inside. I was short of breath. A nurse escorted us into an examination room, and a few minutes later, the oncologist strode in with my MRI images under his arm. He slapped them up on a backlit screen. You see this? he asked. Thats your hip. Now, see that round thing next to it? Thats not supposed to be there.

He reached over to the examination table and began scribbling diagrams on a sheet of sanitary paper. He sketched out what he thought was going on. Although he couldnt be certain without further tests, the tumor was likely a soft-tissue sarcoma, an ugly cancer of the fibers connecting my hip to the muscles and nerve tissues of my left leg. The prognosis depended on how big the tumor was, where precisly it was growing, exactly how aggressive it was. I could get a biopsy of the tumor, which would provide a look at its cellular profile, but there was always the risk of a biopsy needle inadvertently spreading malignant cells outside the tumor itself. What to do?

At worst, this was, well, very bad. At best, a surgeon could cut out the tumor, but might be compelled to sever my femoral nerve, the trunk line that connects the nerves in the leg to the spine. Which meant I would probably never run or ride my bike again. And then Id have to remain vigilant to see if the cancer returned. The doctor ripped off the sheet of sanitary paper, now four feet long, and handed it to me.