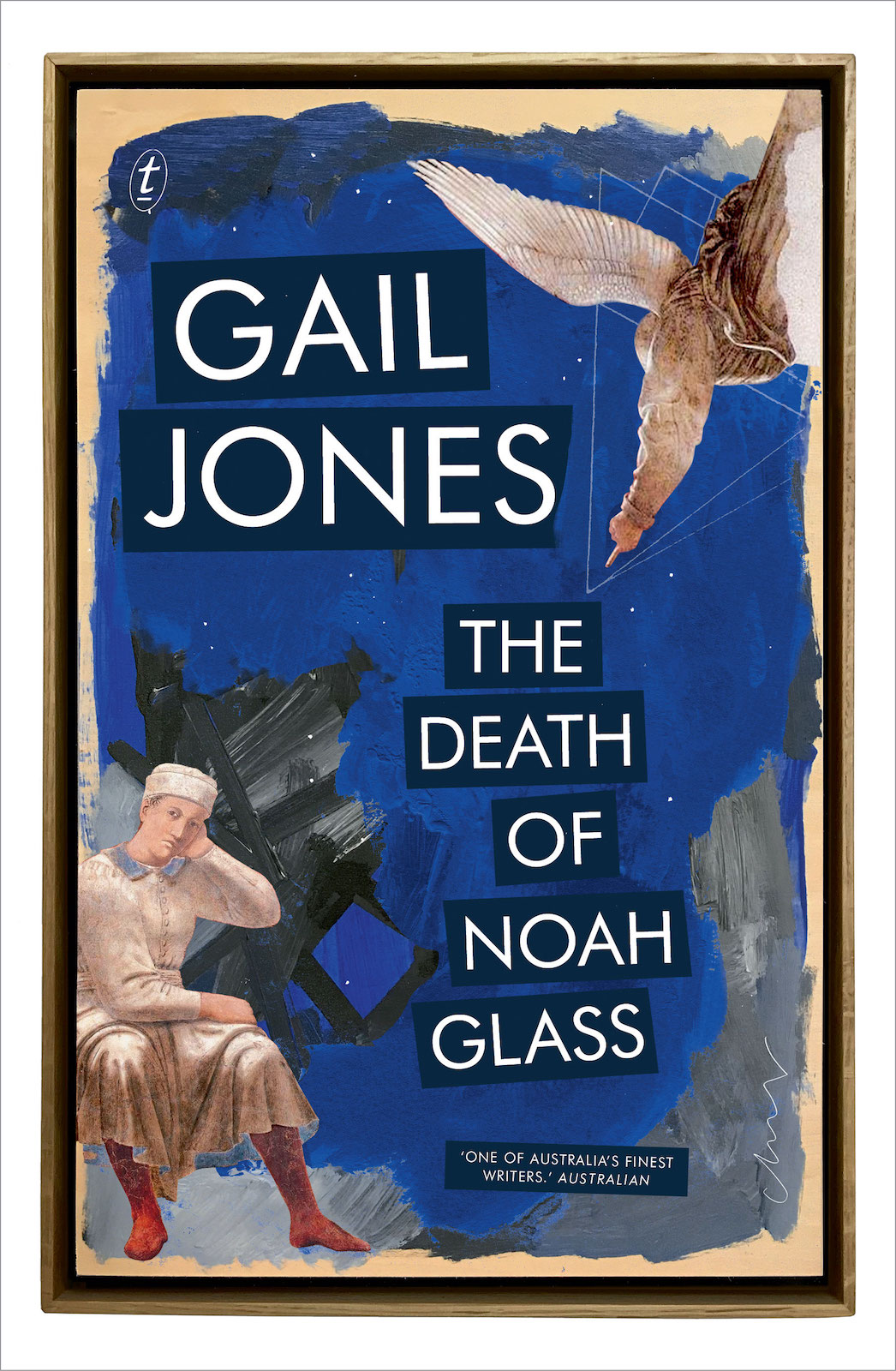

BY THE AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR OF A GUIDE TO BERLIN AND FIVE BELLS

The art historian Noah Glass, having just returned from a trip to Sicily, is discovered floating face down in the swimming pool at his Sydney apartment block. His adult children, Martin and Evie, must come to terms with the shock of their fathers death. But a sculpture has gone missing from a museum in Palermo, and Noah is a suspect. The police are investigating.

None of it makes any sense. Martin sets off to Palermo in search of answers, while Evie moves into Noahs apartment, waiting to learn where her life might take her. Retracing their fathers steps in their own way, neither of his children can see the path ahead.

Gail Joness mesmerising new novel tells a story of parents and children, and explores the overlapping patterns our lives create. The Death of Noah Glass is about love and art, grief and happiness, and the mystery of time.

CONTENTS

Schwerer werden. Leichter sein.

(Grow more heavy. Be more light.)

PAUL CELAN

IN THE CORAL light of a summer dawn, Martin Glass recalled a tale. Two brothers in their late seventies attended the funeral of their father, aged forty-two. The father had disappeared as a young man skiing across country, and in an unseasonable thaw, years later, his frozen body had been exposed. The bright sun shone upon him, ice melted and slid away, and he became a gruesome, implausible and shiny surprise. The trekker who discovered him felt both lucky and appalled. The body might have been a slow-motion swimmer lifting through the surface of the water: first his nose met the air, then his leathery cheeks, and then his damp face, with eyes closed, was revealed to the sky of Chamonix.

Martin imagined the two brothers identifying their father, looking baffled at a version of themselves when young. The corpse was part figurine, with the skin hardened and made inhuman by its preservation, like those bog-men, he supposed, who have the appearance of wood. The fathers clothes would have been old-fashioned and possibly familiar. Perhaps his sons saw again a particular scarf, red and cosy, or recognised a belt, or a woollen hat, or gloves they remembered, stretched long ago over the flexing star of his fingers. Perhaps they stared at these details in order not to dwell on the face. Perhaps one of them thought mummy in a fleeting irreverent second, struck with the impertinence that might come with accident or death. They would have been silent, observed by strangers, formally bereft, looking down at their dead, impossible father. Both must have felt the collapse of time. One brother, the younger, died three weeks after the funeral. The older followed a few months later.

Though hed not thought of it for years, Martin was awoken by this story. Three faces alike, sorry timing, mortal coil. The vex of an accident, its meaninglessness. It afforded the interest of a chance occurrence seeming supernatural. Each man anticipates looking at the face of his old father, possibly standing by the deathbed, possibly assessing his own mortality in the presence of the patriarch: this inversion in sequence compelled and fascinated him. As he lay half-dozing on his back, Martin saw himself as the iceman, confronting the white wall of an untimely death.

Wednesday. This was the day of the funeral. Today he must retrieve the suit he was married in and prepare himself. He must be cautious of his own precarious feelings, he must be manly, and upright, and not lose control, or weep. Martin kicked his legs free of the sheets. He turned from the window and struggled hungover from his bed. His body, always slim, felt abnormally heavy. He rubbed his face with both hands, then his stiff neck, then ruffled his receding and thin grey hair. He felt his skull and wondered with idle alarm about diminishment of memory. Only forty-three, he suspected that his brain was already fretted with holes. Almost every day he found evidence of incipient dementia or a biochemical dysfunction that had no name. Objects receded from definition. People became generalised. Book titles were often difficult to recall. It seemed a dopey belittlement. He was growing smaller in the world, and now, with his father gone, there was a dread, or humiliation, entering the texture of things, like the feeling of walking into a dark room, fumbling for a switch and finding the electricity gone.

In the bathroom, shaving, he barely recognised himself. He was tempted to say his own name aloud. Outside, in the world, he was oddly more credible, an artist who appeared in the newspapers, feted by collectors with a shrewd eye on the markets, linked to the burnished figures of the mysteriously rich. He tilted the mask of his face towards the mirror at a cubist angle. This, apparently, was what it meant to be parentless. One changed appearance, something was peeled away. Shaving cream spattered as he flicked his razor. Martin wiped it to a bleary swirl with the back of his forearm, turned on the tap, and watched the foam of his shaving mess circle and disappear. It would be a day sullied, he knew it, a day full of objects and substances turning into emotions and symbols.

When he heard the phone he started, as if it sounded his nervousness. He considered refusing the command, but realised it was Evie, checking up on him.

So hows it going? he asked.

Did I wake you? Have you remembered?

No. Yes. Of course I remembered.

You found the suit?

Not yet, but I know its here somewhere. Fuck, Evie

Martin paused. He must not swear at his sister or sound exasperated. Shed seen him drunk the night before, wallowing in self-pity. Shed seen him stumble on the pavement and whine like a bullied boy, as though the death of their father, Noah, was a personal affront. He felt the grip of a juvenile shame.

Still ten-thirty?

Yes, that should give us time.

Martin waited for Evie to resume the conversation. There was a pause that he could not decipher.

You okay, Martin?

Shed seen him red-eyed and pathetic. Hed gazed not at a father-artefact, preserved to outlast him, but at an outstretched stranger, already tomb grey. It was not true what they said, that the dead appear to be sleeping. Their father was stony and gone. His mouth hung slightly open. Martin would never tell Evie about the official identification, how hed been disgusted by the force of his own revulsion, that there was a foul odour in the air and a mortal sting. Someone professionally impassive, standing by, had known not to speak or touch his shoulder. Someone else, a stiff clerk, asked him to sign a form. And now Evie was phoning, to check if hed found his suit. He hated the way his younger sister called him to account, made him feel that his misery was undisciplined and trite.

No worries. See you soon.

He hung up. She would guess, no doubt, that he was ashamed of his behaviour, of having made a scene at the restaurant. She was the practical one. She had taken his face in her hands and kissed his moist forehead and said, Well get through this, Martin, we will, we will. Shed hailed the taxi and held his hand and dragged him snivelling into the house, and propped him against the wall with her own body as she reached to flick on the lights. Shed guided him with difficulty to his unmade bed, lowered him to rucked sheets, arranged him, chided softlyJesus, Martinpulled off his stinking shoes and foetid socks. Hed made a weak joke about cowboys dying with their boots on and wanted her gone. Their roles should have been reversed. He should have been the strong one.

In the kitchen Martin half-tripped on his daughters Barbie dollhouse, left behind after her weekend access visit. It was three levels of tiny kitsch, in which everything was coloured fuchsia and open to viewwee tables and chairs, a four-poster bed ringed by a shred of looped gauze, a stove with a minuscule chicken roasting in the oven. Hed won the argument with Angela, who was offended by what she considered its domestic malevolence. Like a pedant Martin lectured her on mass-cultural knowledge, on how charming things in miniature really were, on how children in play are instinctively radical. When she said no, he bought it anyway, wishing to secure Ninas love with a plastic token. He liked to watch her small hands exploring the rooms, pushing furniture here and there, redecorating with her index finger alone. She had the scowl children achieve when they are concentrating with pleasure.