Allan Brown was born in 1967 in Glasgow and has yet to be convinced there is wisdom in leaving. He has been in newspapers since 1990 and is a writer and columnist with the Scottish edition of The Sunday Times, and its restaurant critic. A former Scottish Journalist of the Year, he remains defiant in his belief that Dumfries and Galloway is the most charming, overlooked and quietly batty corner of the British Isles. Even so, he lives in the west end of Glasgow with his wife and children.

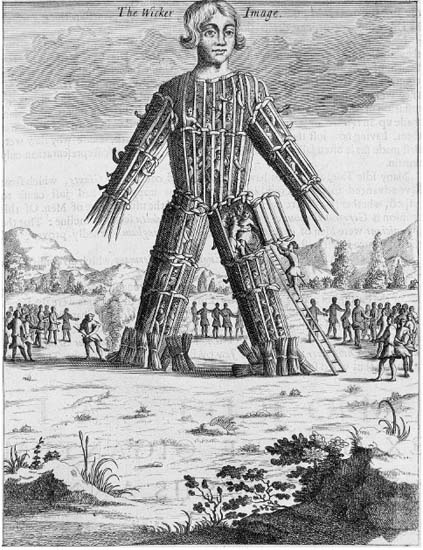

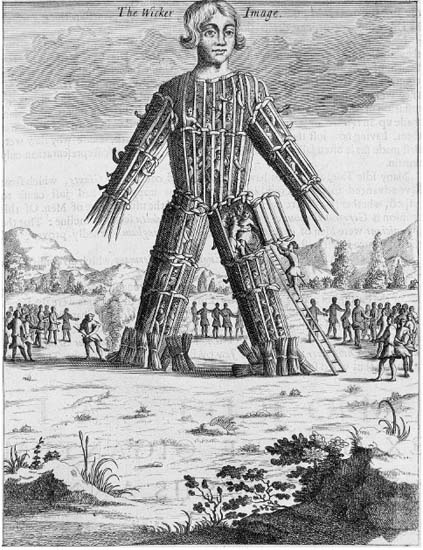

Aylett Sammes, the Wicker image from Britannia Antiqua Illustrata, 1676. Reproduced by permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London

First published in 2000 by Sidgwick & Jackson,

an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd

This ebook edition published in 2012 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Allan Brown 2010

The moral right of Allan Brown to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-217-7

Print ISBN: 978-1-84697-144-0

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

for

Anna, Nina & Joe

This book is in honour of three remarkable men.

Giles Gordon (19402003)

Thomas Nesbitt (19142003)

Anthony Shaffer (19262001)

Acknowledgements

The late Anthony Shaffer was hugely hospitable and cooperative, as were Robin Hardy, Peter Snell, the late Edward Woodward, Christopher Lee, Seamus Flannery, John Herron, Lindsay Kemp, Ingrid Pitt, Britt Ekland, Peter Shaffer, Diane Cilento and Jake Wright. Special thanks must go to the late and widely lamented Giles Gordon and to Gordon Wise at the Curtis Brown agency. Invaluable insights were furnished by A.A. Gill and Kenneth Wright. Gary Gillies and Helen Stewart provided hugely helpful editorial assistance. Canal+ and Optimum Releasing were also very constructive.

This project would have been immeasurably more difficult without two indispensable reference sources: David Bartholomews landmark article on The Wicker Man in Cinefantastique and Stuart Byrons analysis of the films American distribution nightmare in Film Comment magazine.

Thanks also to: Peter Capaldi, Allan Mawn, the deeply alliterative Mike Marshall at Machars Movies, Adrian Turpin, Scott Aitken, Thomas, Catherine and Julie Brown, Iain Brown, John Brown, Julian Cope, the constituent members of Glasgow Rangers Football Club, Martin Gray, Greg Gordon, Jacqueline Houston, Stephen McGinty, Michael Mann, Alison Rae and Neville Moir at Polygon, and, for all the laughs, the aptly-named Liverpudlian. Finally, apologies to Elizabeth McAdam-Laughland of Isle of Whithorn who, thanks to my error, spent a decade with a surname resembling a bad hand of Scrabble.

Foreword

EDWARD WOODWARD

Authors note: this foreword was written in October 1999.

THE MORBID INGENUITIES

The Wicker Man is surrounded by a strange kind of evil. Im not referring to the experience of acting in the film; speaking personally, that was very pleasurable, if somewhat arduous. Nor am I talking about the events within the film itself. I have never considered The Wicker Man to have been a horror film, although I know many people still do: the subject matter, bizarre admittedly, was treated with dignity, the belief systems of both men, Sergeant Neil Howie and Lord Summerisle, were given equal weight and in the end it was a very realistic story, a there-but-for-the-grace-of-God story, about a man who did not deserve his fate, no matter how weird or priggish were his beliefs.

I say the film is surrounded by a strange kind of evil because this seems the only satisfactory explanation for the cruel and senseless treatment it has received at the hands of the film industry over the years. Never mind something being rotten in the state of Denmark; you need only look at the story of The Wicker Man to realize there has always been a fair amount of rottenness spreading from Wardour Street outwards. How could it all have happened? I must plead ignorance, Im afraid. As is the way with actors, I was already on to the next job when The Wicker Man was being slashed in the cutting room and denied a proper release. I do remember my disappointment on discovering that the film would be appearing in cinemas as a mere B-feature: I mean, this was an Anthony Shaffer picture. In contemporary terms that would be like a Steven Spielberg film going straight to video virtually unthinkable! This is not to mention the fact that by 1973 B-features were practically extinct, so the news was a double whammy.

During production of The Wicker Man, I and many others believed that the film would be not only a main feature but a hugely popular one. I was distraught that neither of these things came to pass but, as I said before, life went on and we all had mortgages to pay. It is only now, more than twenty-five years later, that I begin to appreciate what was going on way back then, even if this knowledge only magnifies the sense of injustice. Even today, it is astonishing to think The Wicker Man has not received a major release. The film has proven its worth and its longevity many times over. I have travelled all over the world and everywhere I go, The Wicker Man is mentioned to me within five minutes. I won my role in The Equalizer on American television because the wife of the studio head remembered me from the film. The interest from the media never diminishes; indeed, in recent years it has mushroomed. Wicker Man stills arrive in the post to be autographed all the time. I only wish I knew how we hit such a creative nerve on that film: Id make a few more Wicker Mans and bask in the glory.

As it is, those of us involved at least have the film to bask in. And Im sure that, like me, the others have a wealth of strange, wonderful, happy memories. I have never known a production like The Wicker Man. It was seven frantic weeks of sleepless nights, heavy socializing, fantastically hard work and a kind of wartime Blitz camaraderie. These days, movies are made with every consideration for the sensitivities of the actors, the talent. That was largely true twenty-five years ago too, except, of course, on The Wicker Man, which was shot in a frenzied rush: partly, I understand, for reasons connected with the inadequacy of the films budget; partly because the weather exerted a certain malign influence on the proceedings. Whose idea was it to shoot a movie set at the height of spring on the west coast of Scotland during the onset of winter? I have no idea.

Such difficulties, however, often bring out the best in people, and this was true on The Wicker Man. Making the movie, we struggled through adversity, just as the movie itself later struggled through adversity. In both cases, all was well that ended well, although this doesnt mean I have forgotten the terror I felt being hoisted into the wicker structure one terrifyingly cold day in November, or the panic I experienced on discovering that my final scene had been brought forward, meaning I had to read Howies last prayer from crib sheets suspended on the cliff face opposite. But, then, neither have I forgotten the good bits the wonderful scenery of Dumfries and Galloway, and the kindness shown to us during the films lengthy location shoot. Recently, for the first time in a quarter-century, I returned to the area in which

Next page