Dedication

This collection of stories is dedicated to Manley Elroy MacDonald, a man of uncommon integrity. And to Mary Ellen (Porterfield) MacDonald, a woman of cheer and love. These were my parents.

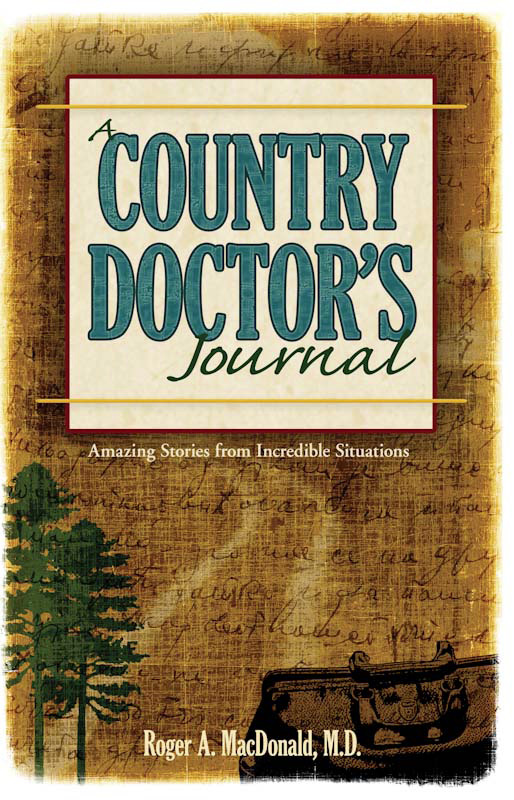

Cover design by Jonathan Norberg

Copyright 2007 by Dr. Roger A. MacDonald, M.D.

Published by Adventure Publications, Inc.

820 Cleveland St. S

Cambridge, MN 55008

1-800-678-7006

www.adventurepublications.net

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-1-59193-210-9 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-59193-297-0 (ebook)

Foreword

The stories in this collection are true. They present glimpses into real-life physician-patient encounters, gleaned from Dr. MacDonalds forty-six years of rural medical experience. In addition, he contacted many of his Minnesota colleagues and asked them to share their recollections of the joys and adventures of being front-line physicians.

Today, barriers of bureaucracy and busy-ness have risen between doctor and patient. A casualty can be a sense of common humanity. Physicians become Providers instead of Doc, while a patient so easily evolves into some roadblock to keeping an efficient schedule. Medicine is becoming Production oriented. These stories return the heart of medicine to where it belongs, the physician using knowledge and skill to help his or her patient.

Ensuring adequate services in out-state settings is a complex challenge. For much of rural Minnesota (and our state is not alone in this), medical care depends on broadly-trained doctors: family physicians, general internists, full-range pediatricians and general surgeons.

How to ensure a supply of such doctors was recognized as a challenge by administrators at two campuses of the University of Minnesota Medical School System. From its inception, the medical school at the University of Minnesota-Duluth accepted as a founding principle the training of students for a rural practice. Beginning in 1970, leaders at the Minneapolis campus of the University of Minnesota Medical School also adopted the goal of providing increased numbers of physicians for rural areas of our state. A unique and aptly named academic effort began. Termed the Rural Physician Associate Program or, affectionately, R-PAP, its thrust was to encourage a student to enter a rural practice. It was conceived by Dr. John Verby, M.D. Volunteer third-year medical students were placed in rural health care facilities for nine to twelve months as part of their formal training. They received close, hour by hour teaching and supervision from qualified frontline physicians. Students learned first-hand that a quality life and competent medical care were possible beyond the city limits of a large urban area.

By now, approximately 1,100 students have taken part in this program. Its example has encouraged similar efforts at medical schools across the nation. In addition to being a grand way to learn clinical medicine, it has succeeded in its goal of persuading graduates to practice where they are most needed.

Through efforts of our universities, through programs such as R-PAP, through the wonderful legacy of former learners teaching new learners, this unique method of teaching can continue for years to come. It is a bond assuring compassionate care of fellow citizens.

Our friends!

Dr. Joseph P. Connolly, M.D.

Emeritus Associate Professor

Co-Director R-PAP (19701975)

Department of Family Medicine and Community Health

Medical School, University of Minnesota

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Introduction

What exactly is a country doctor? More than someone who lives outside big-city limits? A mythic figure to quell fear when it rides the land? An embodiment of strength and wisdom? A person, above all. Ready at hand, compassionate when callous nature strikes. A companion who knows the way to ones home. One whose black satchel carries healing and hope.

A friend.

Those colleagues whom I regard most warmly are fellow country doctors. Similar challenges forge bonds. The endless necessity to keep up on medical advances. The strain of endless emergency call. The endless anxieties that go with practicing in a remote area, where a person with devastating injury or illness can arrive in the office or emergency room. The endless tasks of balancing family responsibilities with demands of medicine!

That rural America needs improved access to health care is evident. Recognition of the fact underlies the recent formation of a division within the Minnesota Department of Health, The Office of Rural Health and Primary Care.

I have heard history described as being of two main streams: top-down or bottom-up. If one considers top-down history as being textbook material, presidents and wars and epochal events, then one can view bottom-up history as events seen through the eyes of an individual. In a diary, a memoir. This collection of stories, of memories, is of the latter variety. It has its own claim to validity; the stories reflect real incidents from ordinary lives.

Still, is any life ordinary?

Confidentiality is a keystone to a professional relationship. How, then, to share the courage, resourcefulness, the humor(!) of my patients within such constrictions was an ever-present challenge. To alter names was obvious, but in a small community not always enough. I changed the locations of my practice towns, dubbing them Northpine. (It is on no map.) When possible, I secured permission from the patient/friend involved to use his or her story. I smudged non-essential details in order to preserve the heart of a persons experience. I pray that I offend no one and that others can learn from the joys and fortitude of my neighbors.

That health care sails troubled seas these days is front-page news. Need exceeds availability. A specter of financial disaster caused by unexpected illness looms over all but the most affluent. We are increasingly locked into a delivery system based on tiers, those with insurance... comprehensive care... and those without, where yawning flaws in the system can prevent a persons receiving even minimal attention. The profession of medicine squirms on the dilemma of whether it provides a service (guaranteeing access for all) or is primarily a business (with profit the decision-maker). Is it not obvious that pharmacy flounders in a similar quagmire of crossed purpose?

I consider myself fortunate. At mid-twentieth century, when my practice years began, such questions barely rumbled on a far horizon.

A small-town practice is so personal. Patients become friends, and friends become patients. One earns esteem; it is not conferred by small print on a diploma.

The life I led as a rural physician was not unique. A number of friends, other country doctors, have submitted accounts of events from their own practices to be herein included. I am grateful to these colleagues for sharing of the wealth from their lives.

The following friends and colleagues have contributed stories to this journal:

Dr. Kenneth Carter, M.D.

Dr. Joseph P. Connolly, M.D.

Dr. Norman Hagberg, M.D.

Dr. Jack, M.D.

Dr. C. Paul Martin, M.D.

Dr. Michael McCarthy, M.D.

Dr. Robert P. Meyer, M.D.

Dr. Robert Nelson, M.D.

Dr. Robert H. Nelson, M.D.

Dr. Vern Olmanson, M.D.

Dr. Ricard Puumala, M.D.

Dr. Thomas Stolee, M.D.

Dr. John Watkins, M.D.

Next page