The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

There is no happiness for him who does not travel, Rohita! Thus we have heard. Living in the society of men, the best man becomes a sinner Therefore, wander!

The feet of the wanderer are like the flower, his soul is growing and reaping the fruit, and all his sins are destroyed by his fatigues in wandering. Therefore, wander!

The fortune of he who is sitting, sits; it rises when he rises; it sleeps when he sleeps; it moves when he moves. Therefore, wander!

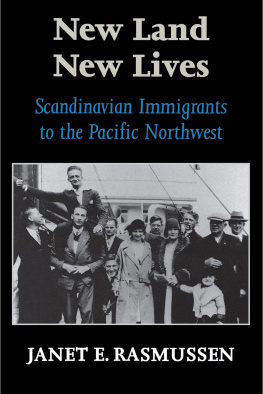

One day in the 1980s, my maternal grandfather was sitting in a park in suburban London. An elderly British man came up to him and wagged a finger in his face. Why are you here? the man demanded. Why are you in my country?

Because we are the creditors, responded my grandfather, who was born in India, worked all his life in colonial Kenya, and was now retired in London. You took all our wealth, our diamonds. Now we have come to collect. We are here, my grandfather was saying, because you were there.

These days, a great many people in the rich countries complain loudly about migration from the poor ones. But as the migrants see it, the game was rigged: First, the rich countries colonized us and stole our treasure and prevented us from building our industries. After plundering us for centuries, they left, having drawn up maps in ways that ensured permanent strife between our communities. Then they brought us to their countries as guest workersas if they knew what the word guest meant in our culturesbut discouraged us from bringing our families.

Having built up their economies with our raw materials and our labor, they asked us to go back and were surprised when we did not. They stole our minerals and corrupted our governments so that their corporations could continue stealing our resources; they fouled the air above us and the waters around us, making our farms barren, our oceans lifeless; and they were aghast when the poorest among us arrived at their borders, not to steal but to work, to clean their shit, and to fuck their men.

Still, they needed us. They needed us to fix their computers and heal their sick and teach their kids, so they took our best and brightest, those who had been educated at the greatest expense of the struggling states they came from, and seduced us again to work for them. Now, again, they ask us not to come, desperate and starving though they have rendered us, because the richest among them need a scapegoat. This is how the game is rigged today.

My family has moved all over the earth, from India to Kenya to England to the United States and back againand is still moving. One of my grandfathers left rural Gujarat for Calcutta in the salad days of the twentieth century; my other grandfather, living a half days bullock-cart ride away, left soon after for Nairobi. In Calcutta, my paternal grandfather joined his older brother in the jewelry business; in Nairobi, my maternal grandfather began his career, at sixteen, sweeping the floors of his uncles accounting office. Thus began my familys journey from the village to the city. It was, I now realize, less than a hundred years ago.

I am now among the quarter billion people living in a country other than the one they were born in. Im one of the lucky ones; in surveys, nearly three-quarters of a billion people want to live in a country other than the one they were born in, and will do so as soon as they see a chance. Why do we move? Why do we keep moving?

On October 1, 1977, my parents, my two sisters, and I boarded a Lufthansa plane in the dead of night in Bombay. We were dressed in new, heavy, uncomfortable clothes and had been seen off by our entire extended family, who had come to the airport with garlands and lamps; our foreheads were anointed with vermilion. We were going to America.

To get the cheapest tickets, our travel agent had arranged a circuitous journey in which we disembarked in Frankfurt, where we were to take an internal flight to Cologne, and then onward to New York. In Frankfurt, the German border officer scrutinized the Indian passports belonging to my father, my sisters, and me and stamped them. Then he held up my mothers passport with distaste. You are not allowed to enter Germany, he said.

It was a British passport, given to citizens of Indian origin who had been born in Kenya before independence, like my mother. But the British did not want them. Nine years earlier, Parliament had passed the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, summarily depriving hundreds of thousands of British passport holders in East Africa of their right to live in the country that conferred their nationality. The passport was literally not worth the paper it was printed on.

The German officer decided that because of her uncertain status, my mother might somehow desert her husband and three small children to make a break for it and live in Germany by herself. So we had to leave directly from Frankfurt. Seven hours and many airsickness bags later, we stepped out into the international arrivals lounge at John F. Kennedy International Airport. A graceful orange-and-black-and-yellow Alexander Calder mobile twirled above us against the backdrop of a huge American flag, and multicolored helium balloons dotted the ceiling, souvenirs of past greetings. As each arrival was welcomed to the new land by their relatives, the balloons rose to the ceiling to make way for the newer ones. They provided hope to the newcomers: look, in a few years, with luck and hard work, you, too, can rise here. All the way to the ceiling.

It was October 2Mahatma Gandhis birthday. We made our way in a convoy of cars carrying our eighteen bags and steamer trunks to a studio apartment in Jackson Heights where The Six Million Dollar Man was playing on the television. On the first night, the building super cut off the electricity because there were too many people in one room. I stepped out and looked at the rusting elevated train tracks above Roosevelt Avenue and wondered: Where was the Statue of Liberty?

At McClancy, the brutal all-boys Catholic high school where my parents enrolled me in Queens, my chief tormentor was a boy named Tschinkel. He had blond hair, piercing blue eyes, and a sadistic smile. He coined a name for me: Mouse. As I walked through the hallways, this word followed me: Mouse! Mouse! A small brown rodent, scurrying furtively this way and that. I was fourteen years old.

One Spanish class, Tschinkel put his leg out to trip me as I was walking in; I kicked hard at it as the entire class whooped. Mouse! Mouse!

As I left the class and walked to the stairwell, I felt a hand shoving me forward. I flew straight down the small flight of stairs and landed on my feet, clutching my books; I could as easily have not, and broken my neck. When I complained to the principal, I was told that such things happen. It was within the normal order of the McClancy day.