This book owes much to many people. Id like to thank our valley neighbours and farm friends, Matias and Ants, Bernardo and Els, Cathy and John, Manolo, Trev, Joan and Patrick; Fernando and Jesus of Nevadensis for the beautiful gentian photo; Staffan Svensson for Swedish prompts and elk sign photos; Pilar Vazquez for Spanish prompts; Carole and Fiona, for more photos, and typing, and being my sisters; and above all, for their forebearance and leading roles in these pages, my heartfelt abrazos to Ana and Chlo.

Once again, my publishers S ORT O F B OOKS have been at the heart of this book and I thank Mark Ellingham and most particularly Natania Jansz, who has nursed and edited the manuscript from its earliest scribblings.

S ORT O F AND C HRIS thank: Peter Dyer for his inspired cover design and work beyond call of duty; Gig Binder for the perfectly timed photo shoots; Henry Iles for all the design within these pages; Gabi Pape for the author photo; Anne Hegerty for proofreading.

The EVENTS, PLACES AND PEOPLE in this book are all real but to protect the innocent, and others, I have changed a few names and details.

I T WAS LATE AT NIGHT and for six long hours I had been driving along an icy tunnel of road into the snowy forest of northern Sweden. I hunched stiffly over the steering wheel to peer along a dismal beam at the monotony of pine trees and snow. One of my headlights had already given up the ghost, snuffed out in a futile struggle against the lashing ice and minus twenty-five degrees cold, and beyond the feeble pallor of its mate and the dim green glow of my dashboard there spread an endless blackness. For more than an hour, now, not a single car had passed me, and not a single lamplight glimmered through the trees. Country Swedes have an appealing tradition of leaving a light burning all night in the window to cheer the passing traveller, but for miles there had been nothing but the deep black of the star-studded sky, and the withering cold. Cocooned in the fuggy warmth of my hired Volvo I had the feeling of being further away from my fellow man than I had ever thought possible.

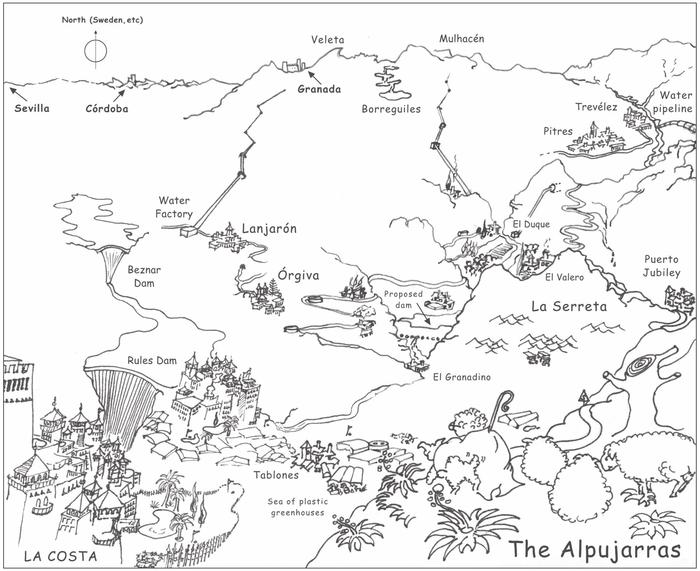

The radio was little help. The only station I had managed to pick up seemed entirely devoted to accordion and fiddle dances, the sort of low-key jolly fare you might expect at the funeral of a popular dog. I found it a little depressing . Instead, to keep awake, I fell into practising Mandarin Chinese, which for years I had been trying to learn. Counting out loud to yourself, yi, er, san, si, wu, is a good way of getting the hang of the tones and it helped me to forget how incredibly lonely I felt. Every time I got to a hundred or so, I would allow my mind to skip back to my home in Spain the sun on a terrace of orange and lemon trees, Ana, my wife, and I lying on the grass, squinting up through the leaves, while our daughter Chlo hurled sticks for the dog and then homesickness would strike with an almost physical stab and Id start again yi, er, san, si, wu

As I worked my way up into the mid-sixties for a third time, the car engine began to play up. Every few minutes its steady rumble would be racked by an alarming series of coughs and judders, and the car would begin to vibrate, rising to a climax of lunatic shuddering. Then it would calm down again and resume its usual rumble.

Each time this happened I was beset by a vivid image of death by freezing. With the air outside at minus twenty-five degrees it wouldnt take long. The warmth of the cabin would dissipate in about ten minutes. That would allow me just enough time to grab all the clothes from my bag and put the whole lot on, capped by the enormous canvas and sheepskin coat (twenty quid in the Swedish Army Surplus), big mittens and woolly hat. My body heat would warm up the ensemble from the inside for about half an hour, then, via the usual process of thermodynamic exchange, the immense body of cold air would invade the tiny body of warmth that was me and overwhelm it. Jumping up and down, running on the spot, all that sort of stuff would prolong the sparks of warmth for a little longer, but I had read somewhere that you shouldnt do too much of it. Just how much was too much, though, I couldnt quite recall.

Still, as the engine revived once again and the car hummed on, I patted the dashboard affectionately in the hope that this would encourage it to shake off its troubles and drive me all the way to Norrskog, the farming village that I was heading for, still hours away through the forest.

I had picked the car up the evening before from Weekies Car Lot, just outside the Copenhagen boat dock. Weekie had looked at me through his thick glasses and a fog of cigarette smoke. Take whichever one you want, he said, from over there, and he pointed with a dismissive gesture to what looked like a scrap yard outside. I stepped out into the bone-chilling cold, the wind whipping across the resund shore, and inspected the offerings. There were old wrecks lying morosely here and there, some slumped down over a flat tyre, others with the bonnets off, revealing engines caked with grease and oil and a light covering of snow. This was where cars belonging to respectable, well-to-do folk came to rest, relegated to a twilight spot as transport for those who couldnt afford a proper hire car. But there was something appealing about Weekies. It was like a sanctuary for old unloved horses; for a minimal fee you could take them out for a ride. I chose a pond-green Volvo, paid the small deposit, slung my kit in the back and headed off along the long long roads to northern Sweden.

I was here for a month to make money shearing sheep in the gloom of winter a job that made enough to keep our small family and farm in Andalucia going for the rest of the year. It seemed that I was doomed to this annual purgatory. Our Spanish mountain farm was a cheap place to live and, with its produce to sustain us, we had few bills or outgoings . But we made hardly any money. There never seemed quite enough to cover the various domestic crises that beset us, like the generator and gas fridge packing up, or a wild boar trashing our new wire fence, or one of Chlos beloved flamenco shoes getting ripped to shreds by the dogs. So these Swedish trips were essential.

As I drove on towards Norrskog, I mused, as I had each year before, on alternative ways of making ready cash. I had one new possibility this year, having sent off a few stories Id written about life on our farm to some publishing friends in London. I wondered what they were making of my handwritten pages too much about sheep and dogs probably and allowed myself to daydream (if thats the right word in a pitch black Swedish afternoon) about a book contract and cheque. Meanwhile I kept a bleary eye open for elk.

Elk are the big danger on Swedish roads. You cant insure against them because the forests are literally swarming with the creatures. They leap out from the trees straight in front of your car just a couple of seconds warning and there they are. If youre unlucky, you knock the legs out from under them a big elk is like a giant horse with antlers and they come hurtling across the bonnet, through the windscreen and into the cabin with you. This intimacy is invariably fatal on both sides. For the elk, because its been hit by a ton of speeding ironwork, and for you because youre pinned to your seat by your belt with an elk thrashing out its death throes in your lap. If youve really got your foot down, they can take the whole top of the car off, along with the top of the occupants. The Swedes do all they can to mitigate this unpleasantness, erecting tall fences along motorways and elk flashers to pick up the lights of cars and flash their warnings into the forest. But there are still hundreds of accidents every year.