A LSO BY M ICHAEL G ORRA

The Bells in Their Silence: Travels through Germany

After Empire: Scott, Naipaul, Rushdie

The English Novel at Mid-Century: From the Leaning Tower

E DITED BY M ICHAEL G ORRA

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (Norton Critical Edition)

The Portable Conrad

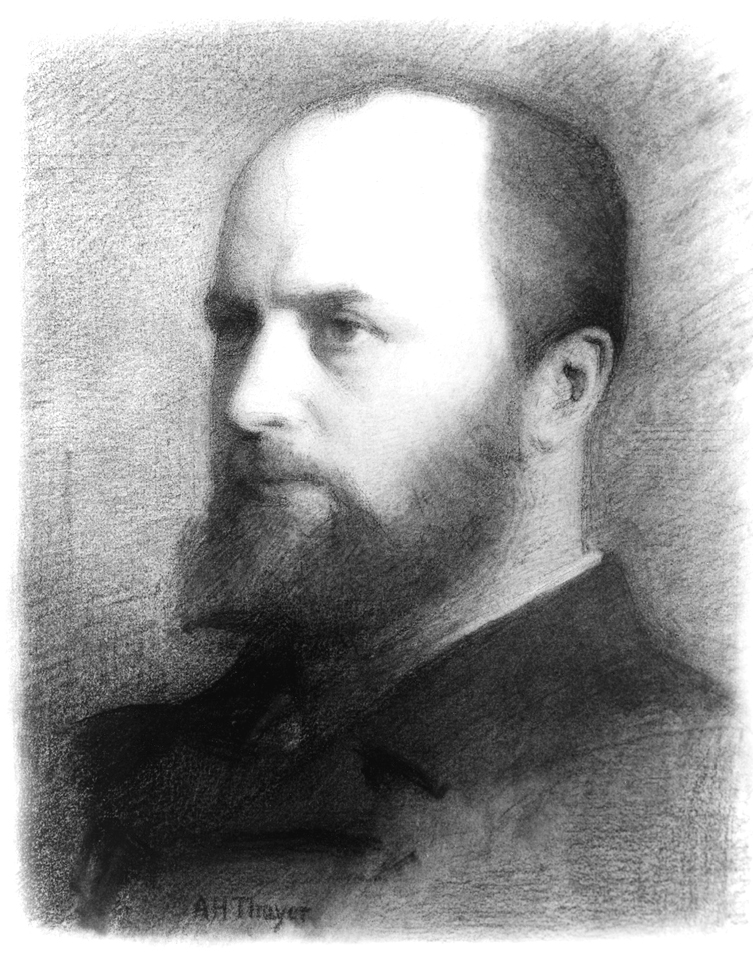

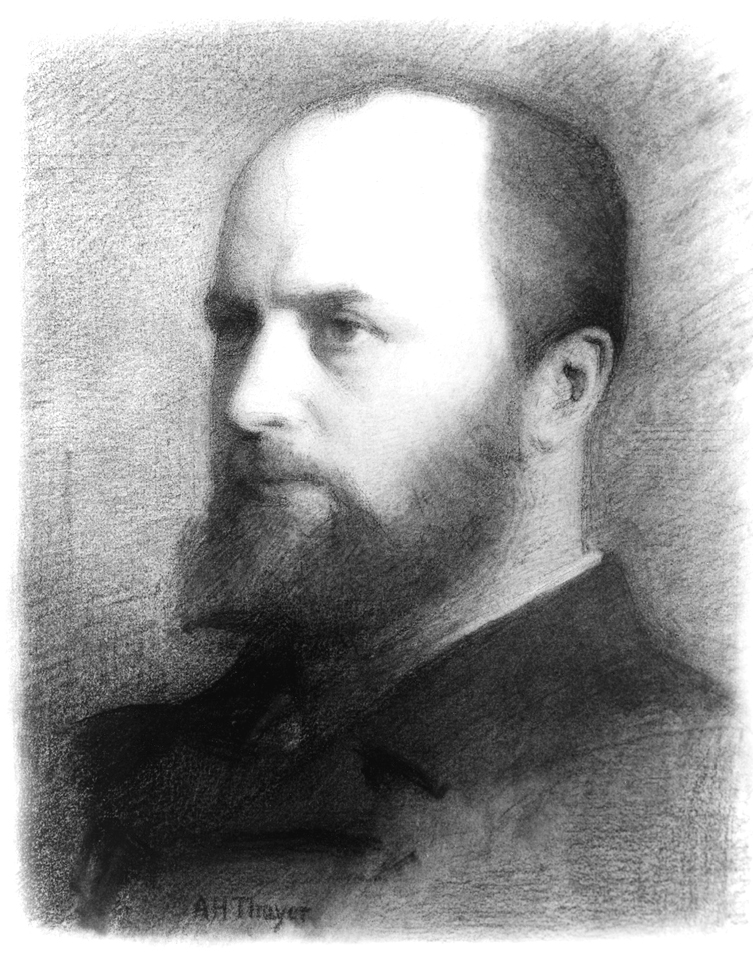

Henry James . By Abbot H. Thayer. Crayon on paper, 1881.

(By permission and from the Collection of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York City)

P ORTRAIT

OF A

OF A

N OVEL

Henry James and the Making of

an American Masterpiece

MICHAEL GORRA

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A Division of W. W. Norton & Company

New York London

FOR M IRIAM

CONTENTS

SEX AND SERIALS, THE CONTINENT AND

THE CRITICS

PROLOGUE

An Old Man in Rye

M ANY YEARS LATER he would remember the way the book had begun. He was old then, and in England, at home in the place he had made for himself, an eighteenth-century brick building called Lamb House in the small Sussex town of Rye. It was a marsh country once known for its shipwrecks and smugglers, thirty miles down the Channel from Dover, and with the town itself resting on top of a hill. Centuries before, it had been directly on the water, but now the coastline had changed, the harbor had silted up, and the flecked blue of the sea lay at a distance of two miles. The ancient port remained charming but had lost its purpose, and the town itself had become an attractive spot for a genteel retirement. It was an odd place for an American novelist, and an odder one for a man whose habits were entirely urban: a figure of clubs and cabs, of dinner parties and first nights. But then he had rarely done the expected thing. He was a famous man, with elaborate manners, and kind; and yet someone whose eyes could drill your spine with their knowledge. Famousbut now little-read, as his royalty figures all too often reminded him. Sometimes he joked about how little his books brought in. His friend Edith Wharton might sell enough to buy a new automobile, but his own checks, he claimed, would only cover the cost of a wheelbarrow.

He had lived in Europe for thirty yearshe had taken possession of it, inhaled it, appropriated it. It had been the great adventure of his life. Or rather his expatriation had made other adventures possible, the adventure contained in the litter of printed sheets on his desk. His literary agent had taken two copies of one of his early novels and cut their bindings, slicing the pages free, and had then pasted each one onto a larger sheet. That gave him a single unbound copy with a few inches of white space on all sides, plenty of room to scrawl. He dipped his pen and blackened half a line of type, wrote four words in the margin and drew a circle around them, with a faint thread of ink tethering them to their place in his paragraph. two more lines, italicized a word of dialogue, turned I am into Im. Another line gone, but this time a new one replaced it, and his characters no longer rejoined in answer to each others speech; instead they returned. Now and then, he revised his first revision. The pen sliced, it cut and it qualified, and sometimes it discovered so many ineptitudes that his quarto sheet became an illegible tangle of lines and arrows. The compositors, he knew, had already complained about such pages, and he put them aside to be typed.

Most nineteenth-century novelists touched up their work in the months between its first publication in a magazine and its appearance as a bound volume. A serial installment might have been rushed to make a deadline or trimmed to match the space, and its opening chapters were usually in print long before the book was finished. But Henry James took the business of revision much further than that. He lived in a world of second thoughts, and in the early years of his career he treated his proofs as but a clean copy, something little better than a draft to scribble over. The pieces a magazine had already printed often got the same treatment. A story from the Atlantic or Harpers might be revised for an American collection, and overhauled again for an English one. He believed that almost every sentence could stand a little work, and could hardly bear to reread his earlier things except with a pen in his hand, making changes as he went. One of his best stories, The Middle Years (1893), gives that habit to its main character, a novelist called Dencombe, who in the storys first pages reworks an advance copy of his latest book. Only this time the new work seems good, and he marks it up with a sense of promise. It makes him realize what he might yet do, and he longs for the chance to grow into a magnificent But Dencombe is also a sick man and he dies before he can grab it.

His creator had better luck. James had made the character die at fifty, but he himself was now sixty-three, and in the spring and summer of 1906 he lived in a season of second chances. The sheets on his desk were from a book he had published in 1881, a quarter of a century ago: The Portrait of a Lady , the novel in which, after a period of careful apprenticeship, he had first allowed his imagination full stretch. He didnt think it was his best bookhe preferred The Ambassadors (1903), a bittersweet comedy about a group of Americans in Parisbut still it was the one from which he brittle intelligence and inflated confidence, would make her an easy mark for the readers criticism if she were not, as James wrote, meant to awaken our sense of tenderness instead.

The Portrait of a Lady was Henry Jamess first true success, and though as a young man he had made fun of the idea of the Great American Novel, greatness had always been on his mind. He had taken pains with the book, and it had changed his reputation. It had made him important enough to be attacked on all sides, and now it was to have a new life. In 1904, James had gone back to the United States, making his first visit in twenty-one years. He saw the places where hed grown up, in New York and Newport and Boston. He gave lectures and gossiped with old friends and was both fascinated and appalled by the way the country had changed, by skyscrapers and a new American language that he barely recognized as his own, so different was its slang and pronunciation. He went to Florida and California and to the battlefields of the Civil War, in which he had not fought, and brought home a mind of gathered impressions that he began to turn into a travel book called The American Scene . But he also matured another plan along the way, arranging with the help of his agent, J. B. Pinker, for the publication by Scribner of a definitive edition of his work; an edition preface; prefaces that now stand, and that to the Portrait in particular, among the most idiosyncratic, and greatest, of his achievements.

T oday, The Portrait of a Lady appears to look backward and forward at once, offering a Janus-faced lens on the history of the novel itself. It is the link between George Eliot and Virginia Woolf, the bridge across which Victorian fiction stepped over into modernism. James used his heroine to crystallize one of his periods central concerns, that of what George Eliot herself had described as the and the result was the most searching account of the moment-by-moment flow of consciousness that any novelist had yet attempted.

Next page

OF A

OF A