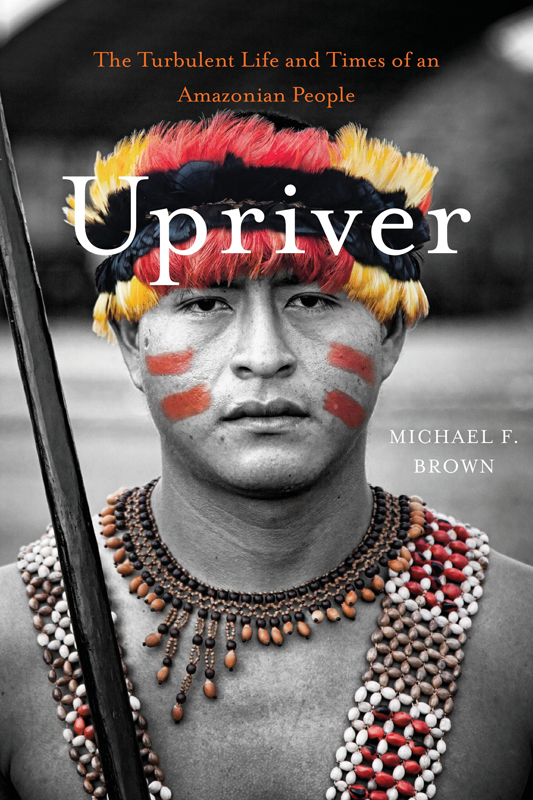

Upriver

Upriver

The Turbulent Life and Times of an Amazonian People

Michael F. Brown

Harvard University Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England

2014

Copyright 2014 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

First printing

Jacket photograph: Desatura la alegria by Marco Schenone

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Brown, Michael F. (Michael Fobes), 1950

Upriver : the turbulent life and times of an Amazonian people / Michael F. Brown.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-36807-1 (alk. paper)

1. Indians of South AmericaPeruAmazonasSocial conditions. 2. Indians of South AmericaPeruAmazonasSocial life and customs. 3. Indians of South AmericaPeruAmazonasFolklore. 4. Amazonas (Peru)Social conditions. 5. Amazonas (Peru)Social life and customs. I. Title.

F3429.1.A3B76 2014

306.0985'46dc23 2014004981

Contents

Spelling of words in the Awajn (Aguaruna) language follows the orthography developed by missionary linguists from SIL International and now used by thousands of literate Awajn. In general, pronunciation is consistent with Spanish. The letter j, for example, is pronounced like the English h; Awajn, therefore, is pronounced like Awahoon. The letter e, however, represents a midcentral vowel closer to the u in the English put than to the Spanish e; the Awajn g approximates the ng of the English ring. For the convenience of readers, I have included stress accents in most Awajn personal names even though the Awajn use them only when required by Spanish writing conventions. Unless otherwise noted, all translations of Awajn and Spanish texts are mine.

Most Peruvians follow the Iberian practice of using both their fathers and mothers surnames in formal settings. To avoid confusing English-speaking readers, I normally use only the first (patrilineal) surname in the main text.

Following standard practice in anthropology, a handful of personal names have been changed to protect individuals whose stories might cause embarrassment or expose them to harm.

On a bitterly cold winter day in 1995, I received a telephone call from a stranger. Her name was Sandra Miller, she said, and she was calling from New Hampshire. She told me that her twenty-six-year-old son, Patchen Miller, had recently been murdered by men who were almost certainly Aguaruna, a people native to the mountainous rainforest region just east of the Andes in northern Peru. She had found my name in the card catalog of her local college library, whose holdings included a book about the Aguaruna that I had written a decade earlier. She hoped that I could help her make sense of the killing. As a practicing Quaker, she insisted, she bore no grudge against the Aguaruna. She simply wanted to understand who they were and why some of them had killed her son.

I knew nothing of the circumstances of the murder other than what Sandra Miller told me. News reports of the attack were only beginning to circulate, and the information they conveyed was sketchy. I fear that I offered little that could have set her mind to rest. Under the circumstances, perhaps no one could.

Later I was able to speak to Patchen Millers traveling companion, Josh Silver, who had been brought up in a town close to my home in western Massachusetts. Josh explained that he and Patchen, inspired by books about adventure travel in Peru, had decided to raft down the Ro Maran to Iquitos, Perus major Amazon port city. On the third night of the river journey, they tied up at an island not far from an Aguaruna village. A young man rowed out to the raft and spent time chatting with them in Spanish. Later they were visited briefly by two men who were less friendly. At about nine-thirty that night, they heard a noise in the forest near the raft. Patchen went to investigate and was hit by a blast from a shotgun. The force of the buckshot spun him into the Maran. Josh was wounded in the leg by a second blast but managed to swim away and hide in dense vegetation on the riverbank. After a night of moving cautiously toward what he hoped would be safety, Josh was rescued by a boatman, also Aguaruna. This man led him to a military post, from which he was rushed to a regional hospital. Josh eventually recovered; Patchens body was never found.

The motive for the crime and the identity of the perpetrators have not been revealed, although it is likely that the Aguaruna themselves know the killers identities. Their goal may have been robbery. It might have had something to do with the border war brewing immediately to the north, along the contested frontier with Ecuador. Deeper conspiracies may have been in play, involving indigenous leaders determined to demonstrate their control over outsiders access to their communities. The two unlucky travelers were pawns in a larger gameor so some Aguaruna intimate today. In the end, all one could say was that an appealing, idealistic young American, someone who hoped to devote his life to progressive causes, fell victim to members of the kind of society he was determined to defend.

As long as there have been hierarchical societies governed by powerful leaders and formal institutions, thinkers have commented on the life of those living just beyond civilizations reach. Their view of such people has been an unstable mix of disdain and envy. The uncivilized are said to live in a state of near anarchy, with too few chiefs and laws, too many gods and wives. Alternatively, they are seen as virtuous innocents unburdened by the tyranny of property or a ruling elite. In Western social thought, Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau hold squatters rights on the extremes of this spectrum. Countless other thinkers have pondered the contrast between the civilized and the not, either directly or by implication: Montaigne, Spencer, Durkheim, Marx, Weber, Simmel, Boas, Benedict, Lvi-Straussthe list is long and distinguished. There is no more foundational question in the social sciences.

There may be no more tiresome one, either. A case in point is the endless fussing over what we should call civilizations

The most serviceable label for an age hypersensitive to linguistic slight is tribal, which at least denotes a particular scale and set of social arrangements. Its clarity is blurred by the notion of tribe, a term that has fallen from favor because of its imprecision. But if we specify that tribal societies are primarily defined by small-scale, family-based relationships and shallow social hierarchies, then the word does useful work.

The philosophical contest between civilizations and tribal societies persists because it serves many ends. Critics of civilization use the intimacy of tribal life as a foil for civilizations grasping ambition, its suffocating hierarchies, and its hivelike specialization. Civilizations boosters, in contrast, portray tribal societies as fated to drift aimlessly while the rest of humanity moves toward mastery of the natural world and more refined ways of organizing social life.

These debates show few signs of slackening. Tribal peoples continue to be put forward as role models of living lightly on the land and practitioners of a spirituality that stands allied with nature rather than being committed to its domination. Environmental activists routinely deploy images of the Kayap, the San, the Cree, and other indigenous peoples as icons of sustainability. This provokes would-be debunkers to claim that these same peoples are guilty of overhunting and other environmental sins.