AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

This is an Apollo book, first published in the UK in 2019 by Head of Zeus Ltd

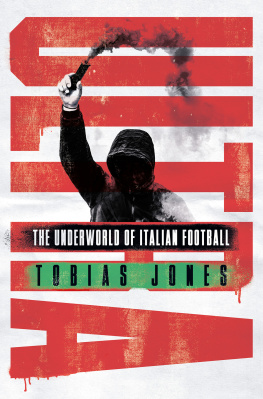

Copyright Tobias Jones, 2019

IMAGE CREDITS:

Image 5 via Facebook, Image 6 via Il Romanista , Image 7 ANSA, Image 11 ANSA, Image 12 Getty / Matthew Ashton, Image 13 via Twitter

Other images are courtesy of Tobias Jones

Every effort has been made to credit the copyright owner of the images

Map Jeff Edwards

Epigraph: Psalms 88:4

The moral right of Tobias Jones to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (HB): 9781786697363

ISBN (E): 9781786697356

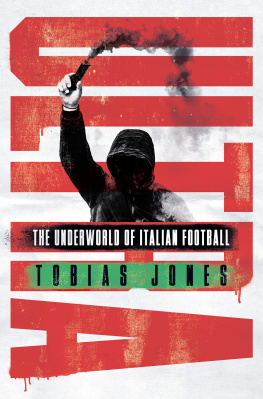

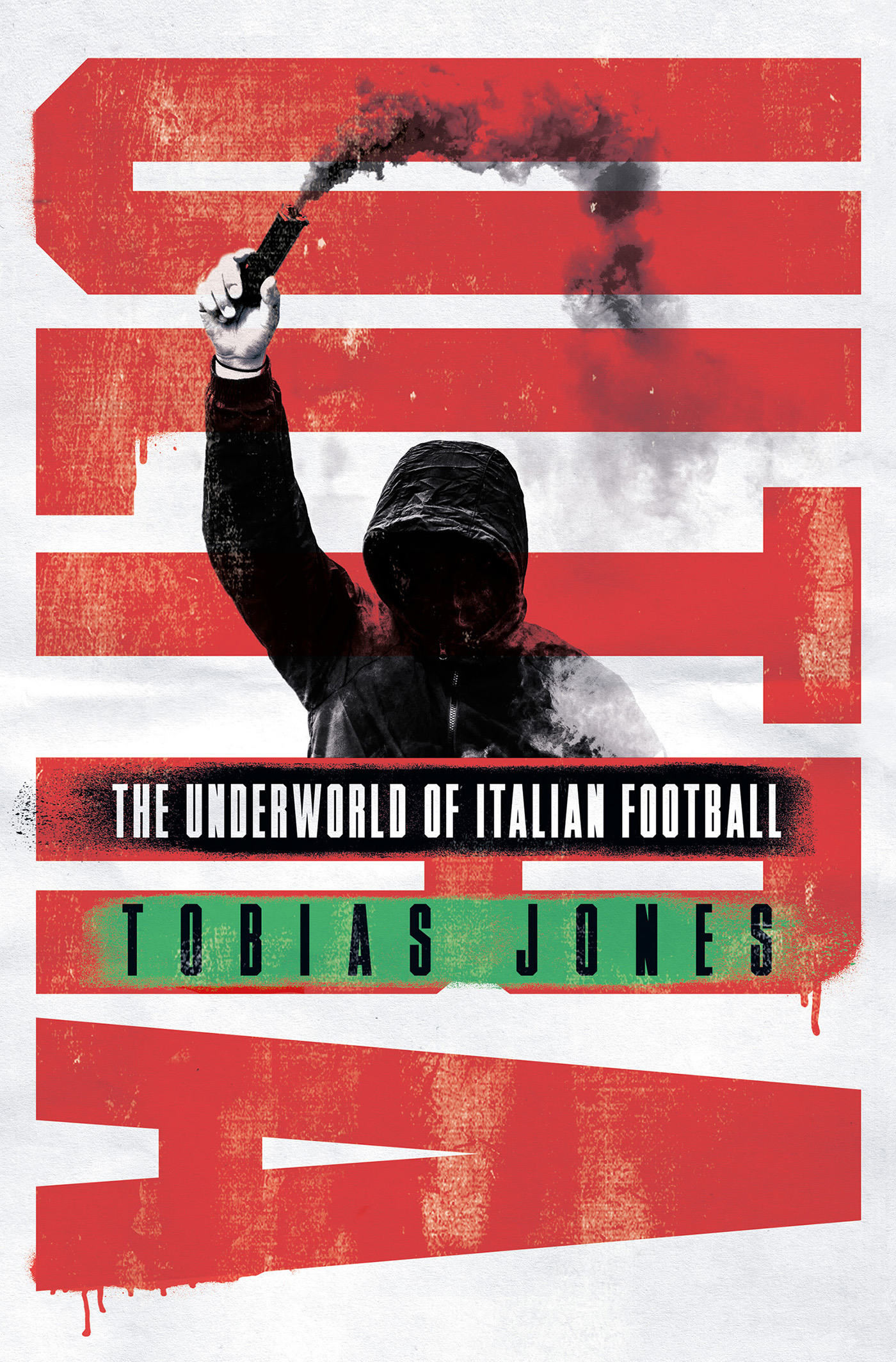

Cover design: JAMES JONES

Cover image: WARREN WONG ON UNSPLASH

Head of Zeus Ltd

First Floor East

58 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

WWW.HEADOFZEUS.COM

Contents

The idea for this book was gifted to me by the great Jon Riley. I dedicate it to him, and to my sport-loving brother, Paul, and his family Marija, Theodore and Kristian with gratitude and admiration.

ormai sono annoverato fra quelli che

scendono nella fossa

Although I love football playing it, watching it, talking about it Ive always thought the fans were more intriguing than the players. Maybe its an ideological inclination towards the masses rather than the elite; or else a belief that the meaning of sport resides not in the champions but in those who are being championed.

In many ways this isnt a book about football at all, but a portrait of an enduring Italian subculture inspired by it. For over fifty years now, the ultras have turned the curve (the curved ends behind the goal) into fairground mirrors of Italian society, offering both a reflection and a distortion of the country. The ultras are a fascinating way to understand not football as such, but why it means so much to people and why a mere rectangle of grass can inspire religious fundamentalism. They are often compared to punks, Hells Angels, hooligans or the South American Barras Bravas , and there are elements of all those groups within the evolving movement. But in truth, its a thoroughly Italian phenomenon drawing on much deeper influences within Italian history.

It is, though, the antithesis of a national movement. The foundation stone of every ultra group is topophilia (love of place) or campanilismo (the attachment to ones local bell-tower). An ultra is a patriot of his or her patch, of a specific town, city or suburb. Its about rootedness and belonging: the sort of pride that persuades people to boast that their forgotten nowhere is actually caput mundi , the capital of the world. Being an ultra is not simply about love for your own town or city, but hatred of the others, especially those close by or even in the same city.

That necessarily creates a problem for a writer attempting to trace the characteristics of a country-wide phenomenon: the ultra world is strangely incomprehensible if you look at it as a national movement, skating across the surface of hundreds of different groups. To do so has the same effect as to study colours (a key ultra concept) by mixing them all together and ending up with none. Thats why I decided to go deep into one particular setting. Whilst always keeping an eye on the national picture, Ive concentrated on a small, ignored city in the deep South, trusting that the provincial can often be universal.

The choice of Cosenza requires a brief justification. Writers are, understandably, drawn to newsworthy events, and the ultras have always made the news. For decades they have been connected to murders, missing persons, bank jobs and drug-dealing, quite apart from the almost routine punch-ups and petty thefts that happen on match days. Yet those cronache nere black chronicles are only partially representative of the ultra world. I actively sought out a curva , or terrace, which might balance the scales, which might even offer some white chronicles as well. Cosenza, I had heard, was a place where the ultras squatted buildings confiscated from the Mafia, giving beds to hundreds of immigrants and destitute Italians. The Cosenza ultras had opened a foodbank for the poor and created Italys first play park for disabled children. One of the most influential fans in the curva was a Franciscan friar. In an era when so many terraces find inspiration in fascism, Cosenza remains devoutly anti-fascist. If anyone was looking for a place to find a counterbalance to the ultra stereotype, Cosenza was clearly it.

The more I went back, the more I felt that the city was an expression of the idealistic origins of the movement back in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was playful, charitable, chaotic and spectacular. I often met Donata Bergamini, the sister of a Cosenza midfielder murdered in 1989, on the terraces. Thirty years after his death, she would be there in the rain with the ultras, supporting a team a thousand kilometres from her home near Ferrara. I truly feel bad, she told me, when Im far from the city and its red-blue colours.

And because Cosenza is a team that has never enjoyed much footballing or financial glory (it has bounced between the lower divisions of Serie D, C and B, going bust now and again), it doesnt draw fans from across the country, let alone the globe. Theres no money to be made. Cosenzas fans are decidedly local and, therefore, offer a far better insight into the rootedness, even poverty, of the ultras than do fans of more decorated teams. Ultras are implacably opposed to the robed dignitaries of modern football, and there was nowhere, I felt, more gloriously ragged than Cosenza.

Ive concentrated on other teams and cities for reasons that will, hopefully, become obvious. One draw has, strangely, been grief. Passion is an integral part of fandom but much more so in its original sense of suffering. When human tragedies far surpass, whilst still reflecting, sporting ones, the ultras role becomes sacred, tending the memory of lives lost and mourned. Another reason Ive been drawn to certain places was a hypothesis, possibly absurd, that ultra groups reflect their topography, so the more beguiling a city (like Genova or Catania) the more curious I was about their crews. Ive been drawn to cities like Rome where there are local rivalries on the asphalt as much as there are on the grass. But Im aware that many other famous groups (from Fiorentina, Napoli, Atalanta and elsewhere) are under-represented and I wouldnt pretend that these pages are anything like exhaustive. Research has been skewed by my personal interests. Clubs with English and Welsh links, a capo-ultra with distant Hollywood connections, places with the best songs, supporters with the most unlikely yarns on the long journey south to Cosenza Ive often been led astray.

But I realize that I have also been drawn to ultra groups that help explain one of the most urgent topics of the early twenty-first century: the resurgence of far-right extremism. The ultras offer a unique vantage point to understand how and why fascism has re-emerged into the mainstream. As you go back through the years, it becomes obvious how hard certain ultras were rubbing the lamp before the genie reappeared. In many ways, the ultras of certain clubs anticipated, by decades, the rhetoric, methods and ideologies that are now dominating political discourse in Italy and elsewhere. If, occasionally, I seem to go off topic its because fascist revivalism is a constant subplot informing and polluting the ultra world.