John Berger - About Looking

Here you can read online John Berger - About Looking full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:About Looking

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

About Looking: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "About Looking" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

About Looking — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "About Looking" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Anthony Barnett, who is always looking.

CONTENTS

WHY LOOK AT ANIMALS?

For Gilles Aillaud

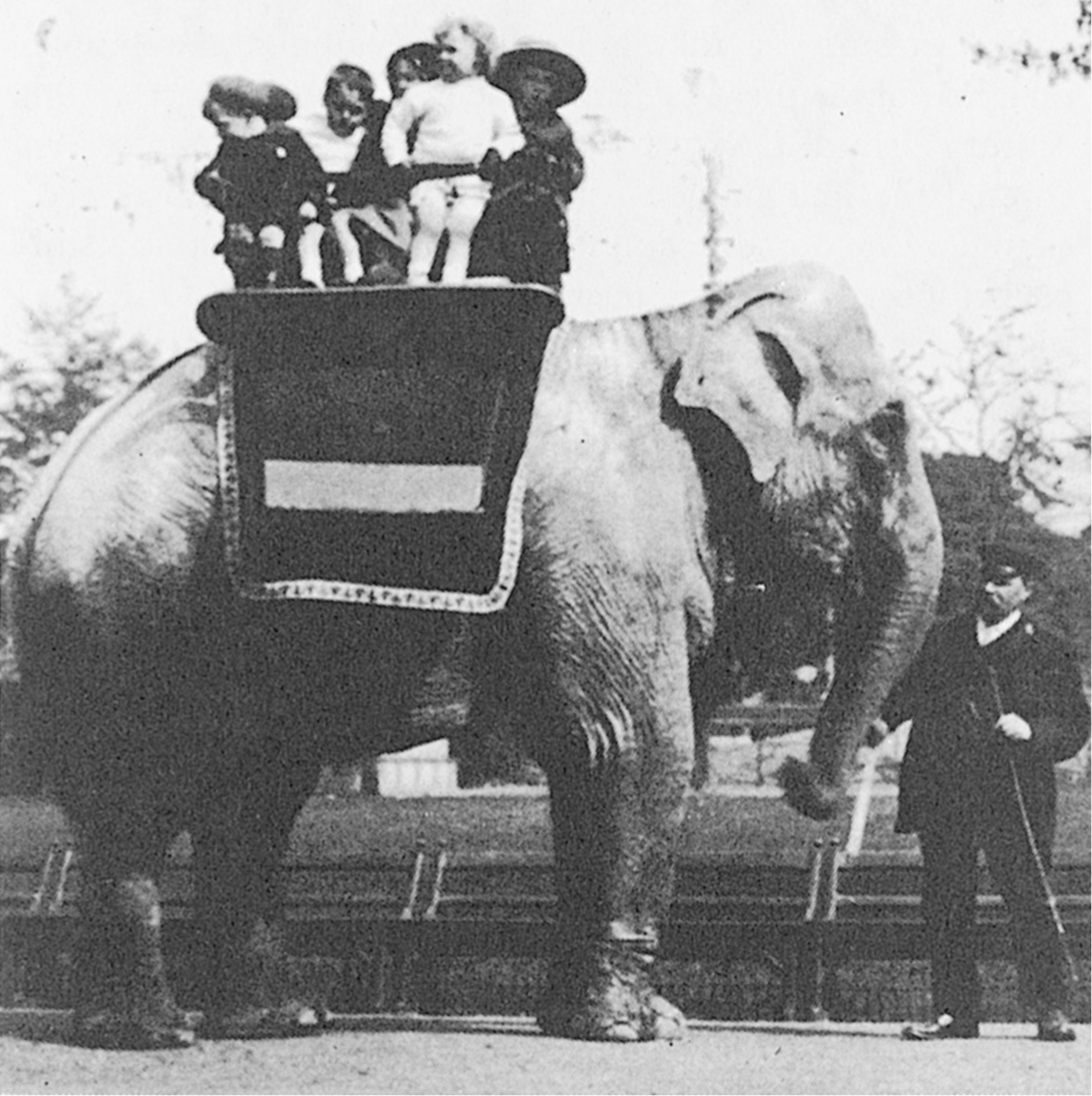

The 19th century, in western Europe and North America, saw the beginning of a process, today being completed by 20th century corporate capitalism, by which every tradition which has previously mediated between man and nature was broken. Before this rupture, animals constituted the first circle of what surrounded man. Perhaps that already suggests too great a distance. They were with man at the centre of his world. Such centrality was of course economic and productive. Whatever the changes in productive means and social organisation, men depended upon animals for food, work, transport, clothing.

Yet to suppose that animals first entered the human imagination as meat or leather or horn is to project a 19th century attitude backwards across the millenia. Animals first entered the imagination as messengers and promises. For example, the domestication of cattle did not begin as a simple prospect of milk and meat. Cattle had magical functions, sometimes oracular, sometimes sacrificial. And the choice of a given species as magical, tameable and alimentary was originally determined by the habits, proximity and invitation of the animal in question.

White ox good is my mother

And we the people of my sister,

The people of Nyariau Bul...

Friend, great ox of the spreading horns,

which ever bellows amid the herd,

Ox of the son of Bul Maloa.

(The Nuer: a description of the modes of livelihood and political institutions of a Nilotic people, by Evans-Pritchard.)

Animals are bom, are sentient and are mortal. In these things they resemble man. In their superficial anatomy less in their deep anatomy in their habits, in their time, in their physical capacities, they differ from man. They are both like and unlike.

We know what animals do and what beaver and bears and salmon and other creatures need, because once our men were married to them and they acquired this knowledge from their animal wives. (Hawaiian Indians quoted by Lvi-Strauss in The Savage Mind.)

The eyes of an animal when they consider a man are attentive and wary. The same animal may well look at other species in the same way. He does not reserve a special look for man. But by no other species except man will the animals look be recognised as familiar. Other animals are held by the look. Man becomes aware of himself returning the look.

The animal scrutinises him across a narrow abyss of non-comprehension. This is why the man can surprise the animal. Yet the animal even if domesticated can also surprise the man. The man too is looking across a similar, but not identical, abyss of non-comprehension. And this is so wherever he looks. He is always looking across ignorance and fear. And so, when he is being seen by the animal, he is being seen as his surroundings are seen by him. His recognition of this is what makes the look of the animal familiar. And yet the animal is distinct, and can never be confused with man. Thus, a power is ascribed to the animal, comparable with human power but never coinciding with it. The animal has secrets which, unlike the secrets of caves, mountains, seas, are specifically addressed to man.

The relation may become clearer by comparing the look of an animal with the look of another man. Between two men the two abysses are, in principle, bridged by language. Even if the encounter is hostile and no words are used (even if the two speak different languages), the existence of language allows that at least one of them, if not both mutually, is confirmed by the other. Language allows men to reckon with each other as with themselves. (In the confirmation made possible by language, human ignorance and fear may also be confirmed. Whereas in animals fear is a response to signal, in men it is endemic.)

No animal confirms man, either positively or negatively. The animal can be killed and eaten so that its energy is added to that which the hunter already possesses. The animal can be tamed so that it supplies and works for the peasant. But always its lack of common language, its silence, guarantees its distance, its distinctness, its exclusion, from and of man.

Just because of this distinctness, however, an animals life, never to be confused with a mans, can be seen to run parallel to his. Only in death do the two parallel lines converge and after death, perhaps, cross over to become parallel again: hence the widespread belief in the transmigration of souls.

With their parallel lives, animals offer man a companionship which is different from any offered by human exchange. Different because it is a companionship offered to the loneliness of man as a species.

Such an unspeaking companionship was felt to be so equal that often one finds the conviction that it was man who lacked the capacity to speak with animals hence the stories and legends of exceptional beings, like Orpheus, who could talk with animals in their own language.

What were the secrets of the animals likeness with, and unlikeness from man? The secrets whose existence man recognised as soon as he intercepted an animals look.

In one sense the whole of anthropology, concerned with the passage from nature to culture, is an answer to that question. But there is also a general answer. All the secrets were about animals as an intercession between man and his origin. Darwins evolutionary theory, indelibly stamped as it is with the marks of the European 19th century, nevertheless belongs to a tradition, almost as old as man himself. Animals interceded between man and their origin because they were both like and unlike man.

Animals came from over the horizon. They belonged there and here. Likewise they were mortal and immortal. An animals blood flowed like human blood, but its species was undying and each lion was Lion, each ox was Ox. This maybe the first existential dualism was reflected in the treatment of animals. They were subjected and worshipped, bred and sacrificed.

Today the vestiges of this dualism remain among those who live intimately with, and depend upon, animals. A peasant becomes fond of his pig and is glad to salt away its pork. What is significant, and is so difficult for the urban stranger to understand, is that the two statements in that sentence are connected by an and and not by a but.

The parallelism of their similar/dissimilar lives allowed animals to provoke some of the first questions and offer answers. The first subject matter for painting was animal. Probably the first paint was animal blood. Prior to that, it is not unreasonable to suppose that the first metaphor was animal. Rousseau, in his Essay on the Origins of Languages, maintained that language itself began with metaphor: As emotions were the first motives which induced man to speak, his first utterances were tropes (metaphors). Figurative language was the first to be born, proper meanings were the last to be found.

If the first metaphor was animal, it was because the essential relation between man and animal was metaphoric. Within that relation what the two terms man and animal shared in common revealed what differentiated them. And vice versa.

In his book on totemism, Lvi-Strauss comments on Rousseaus reasoning: It is because man originally felt himself identical to all those like him (among which, as Rousseau explicitly says, we must include animals) that he came to acquire the capacity to distinguish

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «About Looking»

Look at similar books to About Looking. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book About Looking and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.