ROGER T. AMES, EDITOR

INTIMATE

MEMORY

GENDER

AND

MOURNING

IN

LATE

IMPERIAL

CHINA

MARTIN W. HUANG

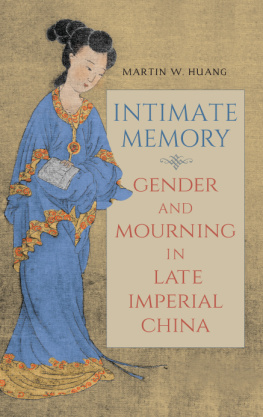

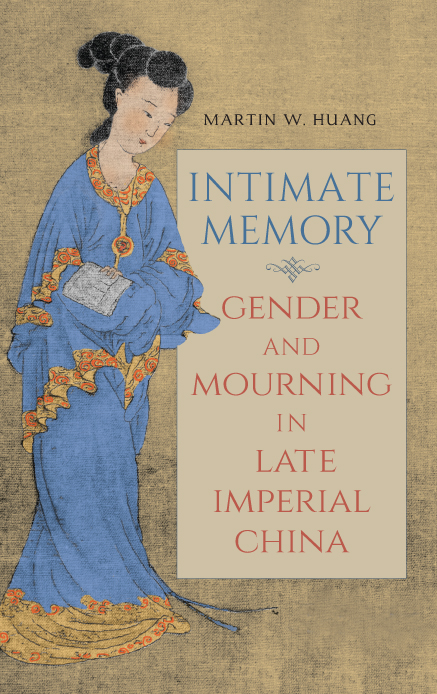

The cover image is a portrait of Zhang Manshu, the concubine of the seventeenth-century writer Mao Qiling, reproduced from the album Manshu liuying assembled by the latter in memory of the former. Facsimile reprint (Shanghai: Shangwu yinshu guan, 1930).

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2018 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Book design: Steve Kress Design

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Huang, Martin W., author.

Title: Intimate memory : gender and mourning in late Imperial China / Martin W. Huang.

Description: Albany, NY : State University of New York, 2018. | Series: SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017019639 (print) | LCCN 2017058852 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438469010 (e-book) | ISBN 9781438468990 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : Loss (Psychology)ChinaHistory. | GriefChinaHistory. | Gender identityChinaHistory. | MemoryChinaHistory.

Classification: LCC BF 575. D 35 (ebook) | LCC BF 575. D 35 H 83 2018 (print) | DDC 155.9/370951dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019639

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In the process of writing this book, I have benefited from the help of many individuals. They include Bob Hegel, Daoxiong Guan, Weijing Lu, Huili Zheng, Sarah Schneewind, and Katherine Carlitz. I consider it my good fortune to have Hu Ying, Michael Fuller, and Qitao Guo as my colleagues here at UC, Irvine, whose help and advice have always been the source of support I rely on.

I am grateful to the following institutions for their generous support in the form of sabbatical leave funding and research stipends: the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation, the University of California President Research Fellowship in the Humanities, and here at UC, Irvine, the Humanities Commons, the Center for Asian Studies, and the Council on Research, Computing, and Libraries.

Portions of , under the title The Manhood of a Pinshi (A Poor Scholar): The Gendered Spaces in The Six Records of A Floating Life , has appeared in the volume Changing Chinese Masculinities from Imperial Pillars of State to Global Real Men , edited by Kam Louie and published by Hong Kong University Press in 2015. I thank Kam for inviting me to present an earlier draft of the article at the conference he organized at Hong Kong University.

Finally, my thanks go to SUNYs two anonymous outside readers for their thoughtful comments on the manuscript; although I may not have been able to follow all their suggestions in my subsequent revision, their input was valuable and much appreciated. Of course, any errors remaining in the book are strictly my own.

INTRODUCTION

Barely four months after bidding farewell to his family, the early Qing scholar-official and dramatist You Tong (16181704) received the devastating news in the capital a thousand li away that his wife had passed away in his hometown more than a month earlier. To mourn his late wife, the distraught You Tong wrote an emotional biographical sketch. Tormented by the guilty feelings of not being at her bedside when she needed him most, You Tong wrote:

Alas, how sad! I dont know ( zhi ) how my wife died. We have been married for forty years. Then she died only one hundred days after I left her [for the capital]. I only know how my wife lived but I dont know how she died. For someone who knows how she died, his sorrow is probably not as deep as someone who only knows how she lived. Then if I dont know how my wife died, how could I really know how she lived? Our son Zhen came to me in his mourning clothes and pleaded: I know a few things about the life of my mother but I am too distraught to write. My father, how could you bear to desert your children [by failing to keep alive the memories of their mother]?

Here the emotional intensity of a grieving husband is quite palpable, and the feeling of guilt dominates. Seemingly wondering about his own ability to truly know his deceased wife, You Tong emphasized the importance of zhi (understanding and knowing), implying he himself was nevertheless the most qualified person to reconstruct and record the life of his wife since they had lived together as husband and wife for so many decades. He concluded the sketch with the following passage:

We were a couple that had gone through all the hardships together and I have never had any concubines ( bingwu qieying ). Being husband

It had become quite common by the seventeenth century for a grieving husband to write a fairly long and emotional elegiac prose essay to honor his deceased wife in the form of a biographical account. You Tong felt the urgent need to turn her life into a scribed text, which was supposed to be endowed with the ultimate power to transcend death and time.

Considering himself the one who knew his wife best, he insisted he was the most appropriate person to author such a textualized life, whereas the tremendous pains of loss turned him into a particularly sympathetic as well as revealing biographer. At the same time, even with such conviction of a uniquely-privileged biographer, You Tong might still feel the pressure to apologize for his outpouring of siqing or selfish feelings. He felt the need to legitimate his elegiac act by suggesting that he wrote this biography at the request of their son, whose filial love for his mother, different from a husbands siqing for his wife, hardly needed any apology given the Confucian notion of filiality. There was an obvious tension between the Confucian inhibitions over direct expressions of conjugal attachment and the desire to remember and commit to writing the detailed facts in the life of his wife in a way only he could do.

Despite his somewhat conventional reliance on the filial need of their son as an excuse for writing about the life of his late wife, You Tongs biographical sketch points to what was then an emerging trenda late imperial literatus increasing willingness to acknowledge that he was writing about the life of his wife not necessarily for her Confucian exemplariness or even for the purpose of preserving a record of her life for their decedents, but for the sake of his own memory: she was being remembered first of all as someone who had been very close to him. This was a project of personal remembrance based on intimate memory, which was often associated with si (the private or even the selfish), a rather reprehensible undertaking, at least in the eyes of the more conservative. It was the intimate, or eye-polluting ( chenmu ; to use a variation of You Tongs own wording) details of the life they shared together that was most worth remembering.