The NHLs Mistake by the Lake

Also by Gary Webster and from McFarland

The League That Didnt Exist: A History of the All-American Football Conference, 19461949 (2019)

Just Too Good: The Undefeated 1948 Cleveland Browns (2015)

When in Doubt, Fire the Skipper: Midseason Managerial Changes in Major League Baseball (2014)

.721: A History of the 1954 Cleveland Indians (2013)

Tris Speaker and the 1920 Indians: Tragedy to Glory (2012)

The NHLs Mistake by the Lake

A History of the Cleveland Barons

Gary Webster

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

ISBN (print) 978-1-4766-8584-7

ISBN (ebook) 978-1-4766-4400-4

Library of Congress and British Library cataloguing data are available

Library of Congress Control Number 2021042692

2021 Gary Webster. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

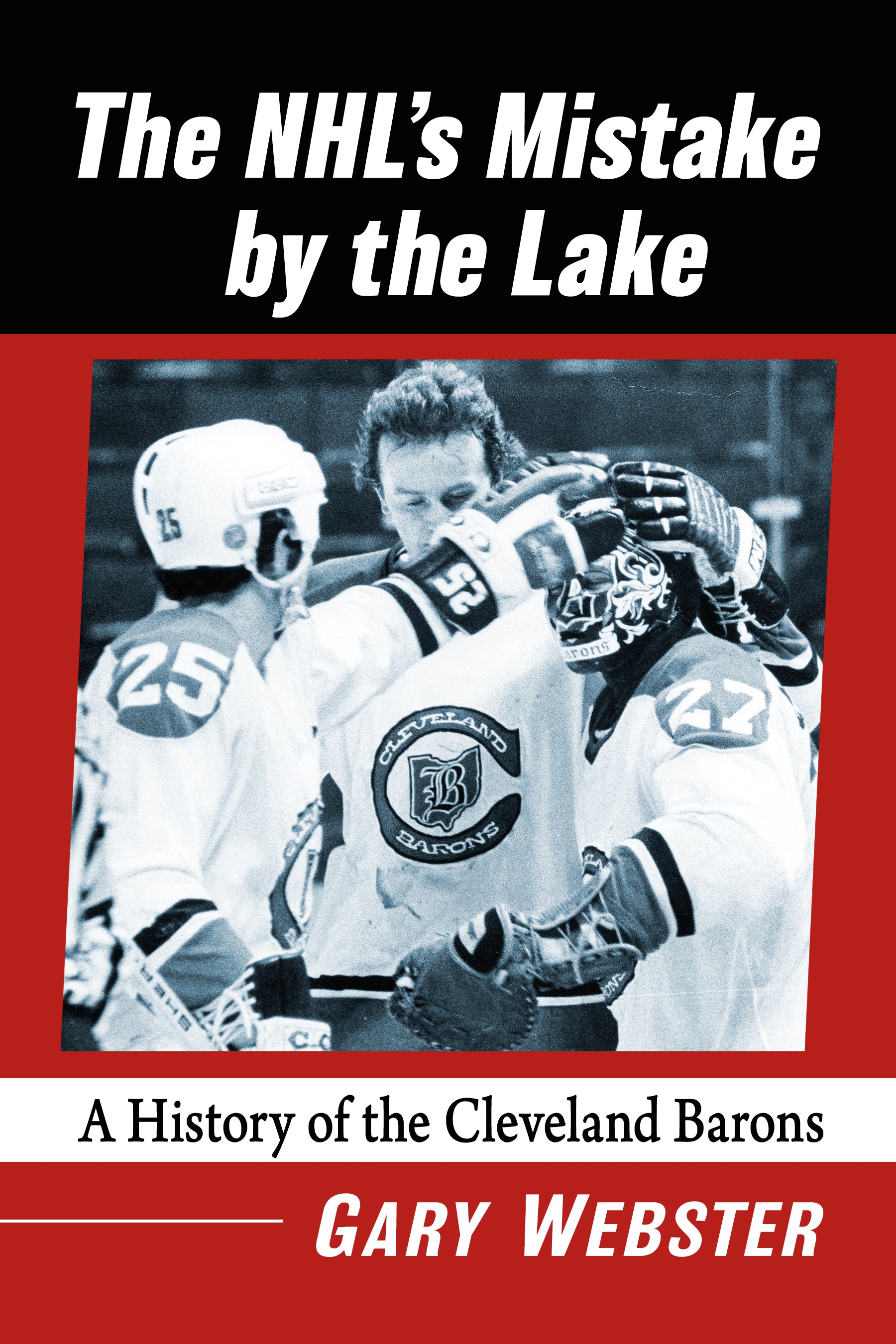

Front cover image: Barons goaltender Gilles Meloche is congratulated by teammates Al MacAdam (25) and Walt McKechnie after a rare victory at the Richfield Coliseum during the 1977-78 season. (Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University)

Printed in the United States of America

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Table of Contents

Introduction

This was the way it was supposed to have been.

On a Saturday night in June of 2016, almost 20,000 fans rose to their feet in Clevelands Quicken Loans Arena after Oliver Bjorkstrand poked the puck into the opposing teams net with less than two seconds to play in the first sudden death overtime period, giving the home team a thrilling 10 victory and a four-game sweep of the championship finals. The crowd was the second largest in American Hockey League history, which dates back to 1935. The victory in the cup finals was the first by a hockey team representing Cleveland in 52 years.

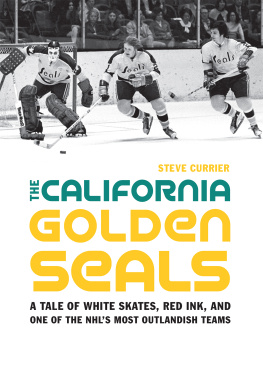

The bedlam in Quicken Loans Arena was precisely what Mel Swig had envisioned when he and his co-owners, George Gund III and Bud Levitas, hastily moved the Oakland-based California Golden Seals of the National Hockey League to Cleveland in the summer of 1976. But the cup hoisted by the players in 2016 wasnt the Stanley Cup. It was the Calder Cup, symbolic of the championship of the American Hockey League, the sports highest minor league. And though the players hoisting the Calder Cup wore the same red, white and black colors, they werent the Barons of Swig, Gund and Levitas. They were the Lake Erie Monsters, who took the place of the two minor league clubs that succeeded the Barons. Swigs team lasted just two seasons in the Richfield Coliseum, the sports palace halfway between Cleveland and Akron. Swig owned the team for only the first of those seasons. It never came close to filling the Coliseum even once, as the Monsters had done in Quicken Loans Arena the night they won the Calder Cup.

The Monsters triumphant moment should never have happened, because the Barons should never have faltered as badly as they did after relocating to Cleveland, a city with a proud hockey tradition. The 20152016 season should have been the franchises 39th in northeastern Ohio, and the cup they would have been competing for would have been Lord Stanleys, the oldest prize in professional sports. But the Barons, and the NHL, departed Cleveland after two miserable seasons, leaving the city without a hockey team for 14 years. The International Hockey League transferred its Muskegon, Michigan, franchise to Cleveland in 1992. When that league folded, the AHL, of which the original Barons had been a member from 1937 until 1973, returned.

Sports writers have long observed that otherwise smart and astute businesspeople often check their acumen at the door when they purchase a professional sports team. Such was the case with Swig and Gund when they decided that they couldnt keep the Golden Seals in Oakland one more minute. A gleaming new building in northeastern Ohio beckoned, and the decision to move the team there seems to have consisted of little more than Gund, a native Clevelander, suggesting to Swig that he transfer the Golden Seals to Cleveland and Swig, after considering the suggestion for all of 30 seconds, responding, Sure, why not? Had Swig and Gund run the businesses that made their families rich the same way they would run the renamed Golden Seals once they arrived in Cleveland, theyd never have had the money to invest in professional hockey in the first place. Theyd have been fortunate to find the money to buy a ticket to watch someone elses team play.

The Cleveland Barons of the NHL are the last major league sports franchise in North America to fold. Their demise could almost have been foretold from the moment they arrived in July of 1976. Swig and, later and to a lesser extent, Gund and his brother Gordon seemed to think that the NHL brand alone would be more than enough to attract large crowds to the Coliseum to watch an inferior product. And northeastern Ohios hockey fans, for some reason, seemed to resent the Barons rather than welcome them.

The decade of the 1970s was a tough one for Cleveland. Jokes about the city abounded in the national media, some of them well-deserved. The Cleveland Barons were one of those jokes. This book is for northeastern Ohio hockey fans who have the stomach to relive the citys mercifully brief flirtation with the National Hockey League. And for anyone who enjoys reading about a good disaster. Because theres no other way to describe Clevelands experience with major league hockey between July of 1976 and June of 1978. And theres no other way of describing major league hockeys experience with its Oakland/Cleveland franchise between 1967 and 1978. It was an $11 million fiasco, the last 23 months of which are revisited in detail in the pages that follow.

This Town Aint Big Enough for Both of Us

Cleveland and the National Hockey League were never meant to be.

The embarrassment to both the league and the city that was the ill-fated Cleveland Barons of 19761978 might have been avoided if Al Sutphin hadnt been so loyal to his fellow team owners in the American Hockey League following the 194142 season. Sutphins Barons had dominated the AHL, both on the ice and at the box office, since joining the league for the season of 193738. During the season of 194041, the Barons, playing in the five-year-old Cleveland Arena on Euclid Avenue at East 36th Street, had averaged 8,267 spectators per home game. That exceeded the per-game averages of both of the NHLs New York clubs, the Rangers and Americans, plus the Detroit Red Wings and the fabled Montreal Canadiens. A few years earlier, it had been rumored that Montreals other NHL team, the Maroons, was looking to relocate to Cleveland. Instead, the Maroons simply folded. By the spring of 1942, the NHL was casting covetous glances toward Cleveland, and the Barons were listening.

Less than six months after Pearl Harbor, the Second World War had begun to affect professional sports by siphoning off manpower for the armed forces. Able-bodied athletes were enlisting in large numbers, and those who didnt volunteer were being drafted in both the United States and Canada with the latter providing the vast majority of the players in the National and American hockey leagues. The New York Americans were faltering both on and off the ice and would soon leave the NHL. Owners were concerned about their ability to maintain fan interest with just half a dozen teams and looked to expand by adding the AHLs Cleveland and Buffalo clubs. The Barons were the AHLs gold standard. The Bisons were properly situated geographically, being close to Detroit and Toronto (and Cleveland), and would give the NHL an even number of clubs, ensuring no one would be idle on lucrative Friday and Saturday nights, thus missing out on precious ticket (and concession) revenue.