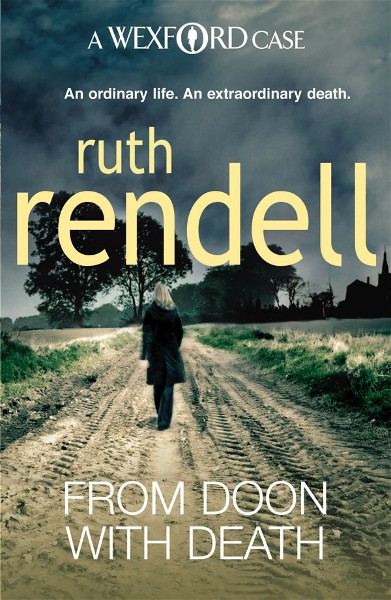

You have broken my heart There, I have written it. Not for you to read, Minna, for this letter will never be sent, never shrink and wither under your laughter, little lips prim and pleated, laughter like dulcimer music...

Shall I tell you of the Muse who awaited me? I wanted you to walk beside me into her vaulted halls. There were the springs of Helicon! I would furnish you with the food of the soul, the bread that is prose and the wine that is poetry. Ah, the wine, Minna... This is the rose-red blood of the troubadour!

Never shall I make that journey, Minna, for when I brought you the wine you returned to me the waters of indifference. I wrapped the bread in gold but you hid my loaves in the crock of contempt.

Truly you have broken my heart and dashed the winecup against the wall...

Chapter 1

Call once yet, In a voice that she will know, Margaret, Margaret!

Matthew Arnold, The Forsaken Merman

I think youre getting things a bit out of proportion, Mr Parsons, Burden said. He was tired and hed been going to take his wife to the pictures. Besides, the first things hed noticed when Parsons brought him into the room were the books in the rack by the fireplace. The titles were enough to give the most level-headed man the jitters, quite enough to make a man anxious where no ground for anxiety existed: Palmer the Poisoner, The Trial of Madeleine Smith, Three Drowned Brides, Famous Trials, Notable British Trials.

Dont you think your reading has been preying on your mind?

Im interested in crime, Parsons said. Its a hobby of mine.

I can see that. Burden wasnt going to sit down if he could avoid it. Look, you cant say your wifes actually missing. Youve been home one and a half hours and she isnt here. Thats all. Shes probably gone to the pictures. As a matter of fact Im on my way there now with my wife. I expect well meet her coming out.

Margaret wouldnt do that, Mr Burden. I know her and you dont. Weve been married nearly six years and in all that time Ive never come home to an empty house.

Ill tell you what Ill do. Ill drop in on my way back. But you can bet your bottom dollar shell be home by then. He started moving towards the door. Look, get on to the station if you like. It wont do any harm.

No, I wont do that. It was just with you living down the road and being an inspector...

And being off duty, Burden thought. If I was a doctor instead of a policeman Id be able to have private patients on the side. I bet he wouldnt be so keen on my services if there was any question of a fee.

Sitting in the half-empty dark cinema he thought: Well, it is funny. Normal ordinary wives as conventional as Mrs Parsons, wives who always have a meal ready for their husbands on the dot of six, dont suddenly go off without leaving a note.

I thought you said this was a good film, he whispered to his wife.

Well, the critics liked it.

Oh, critics, he said.

Another man, that could be it. But Mrs Parsons? Or it could be an accident. Hed been a bit remiss not getting Parsons to phone the station straight away.

Look, love, he said. I cant stand this. You stay and see the end Ive got to get back to Parsons.

I wish Id married that reporter who was so keen on me.

You must be joking, Burden said. Hed have stayed out all night putting the paper to bed. Or the editors secretary.

He charged up Tabard Road, then made himself stroll when he got to the Victorian house where Parsons lived. It was all in darkness, the curtains in the big bay downstairs undrawn. The step was whitened, the brass kerb above it polished. Mrs Parsons must have been a house-proud woman. Must have been? Why not, still was?

Parsons opened the door before he had a chance to knock. He still looked tidy, neatly dressed in an oldish suit, his tie knotted tight. But his face was greenish grey. It reminded Burden of a drowned face he had once seen on a mortuary slab. They had put the glasses back on the spongy nose to help the girl who had come to identify him.

She hasnt come back, he said. His voice sounded as if he had a cold coming. But it was probably only fear.

Lets have a cup of tea, Burden said. Have a cup of tea and talk about it.

I keep thinking what could have happened to her. Its so open round here. I suppose it would be, being country.

Its those books you read, Burden said. Its not healthy. He looked again at the shiny paper covers. On the spine of one was a jumble of guns and knives against a blood-red background. Not for a layman, he said. Can I use your phone?

Its in the front room.

Ill get on to the station. There might be something from the hospitals.

The frontroom looked as if nobody ever sat in it. With some dismay he noted its polished shabbiness. So far he hadnt seen a stick of furniture that looked less than fifty years old. Burden went into all kinds of houses and he knew antique furniture when he saw it. But this wasnt antique and. nobody could have chosen it because it was beautiful or rare. It was just old. Old enough to be cheap, Burden thought, and at the same time young enough not to be expensive. The kettle whistled and he heard Parsons fumbling with china in the kitchen. A cup crashed on the floor. It sounded as if they had kept the old concrete floor. It was enough to give anyone the creeps, he thought again, sitting in these high-ceilinged rooms, hearing unexplained inexplicable creaks from the stairs and the cupboard, reading about poison and hangings and blood.

Ive reported your wife as missing, he said to Parsons. Theres nothing from the hospitals.

Parsons turned on the light in the back room and Burden followed him in. It must have a weak bulb under the parchment lampshade that hung from the centre of the ceiling. About sixty watts, he thought. The shade forced all the light down, leaving the ceiling, with its plaster decorations of bulbous fruit, dark and in the corners blotched with deeper shadow. Parsons put the cups down on the side board, a vast mahogany thing more like a fantastic wooden house than a piece of furniture, with its tiers and galleries and jutting beaded shelves. Burden sat down in a chair with wooden arms and seat of brown corduroy. The lino struck cold through the thick soles of his shoes.

Have you any idea at all where your wife could have gone?

Ive been trying to think. Ive been racking my brains. I cant think of anywhere.

What about her friends? Her mother?

Her mothers dead. We havent got any friends here. We only came here six months ago.

Burden stirred his tea. Outside it had been close, humid. Here in this thick-walled dark place, he supposed, it must always feel like winter.

Look, he said, I dont like to say this but somebodys bound to ask you. It might as well be me. Could she have gone out with some man? Im sorry, but I had to ask.

Of course you had to ask. I know, its all in here. He tapped the bookcase. Just routine enquiries, isnt it? But youre wrong. Not Margaret. Its laughable. He paused, not laughing. Margarets a good woman. Shes a lay preacher at the Wesleyan place down the road.

No point in pursuing it, Burden thought. Others would ask him, probe into his private life whether he liked it or not; if she still hadnt got home when the last train came in and the last bus had rolled into Kingsmarkham garage.

I suppose youve looked all over the house? he asked. He had driven down this road twice a day for a year but he couldnt remember whether the house he was sitting in had two floors or three. His policemans brain tried to reassemble the retinal photograph on his policemans eye. A bay window at the bottom, two flat sash windows above it and - yes, two smaller ones above that under the slated eyelids of the roof. An ugly house, he thought, ugly and forbidding.

Next page